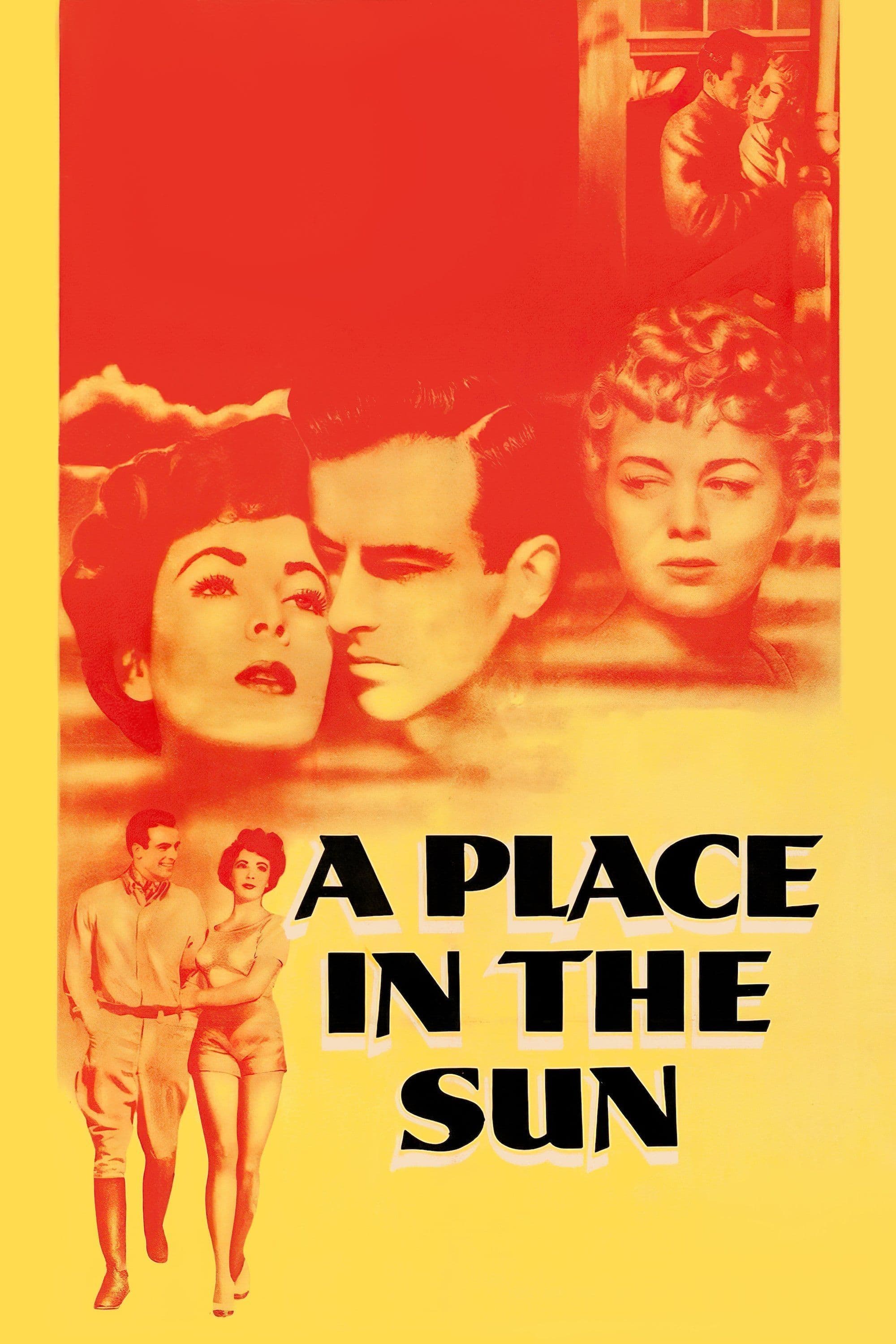

A Place in the Sun

1951

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Drawn from Theodore Dreiser’s celebrated novel “An American Tragedy,” whose naturalistic density and incisive analysis of American social impulses seemed almost recalcitrant to cinematic transposition, A Place in the Sun not only manages to equal its august predecessor in social commentary, emotional lyricism, and moral introspection, but indeed reshapes the material into a cinematic form that enhances its most intimate dramatic power. George Stevens, with a mastery that transcends mere slavish reproduction, appropriates Dreiser’s deterministic fatalism to imbue it with a more visceral, almost operatic breath, transforming the true crime case into a universal parable on human fragility and the chimeras of ambition.

The protagonist, George Eastman – a Montgomery Clift of mournful and tormented beauty, almost an archetype of post-war youthful disquiet – is a penniless young man, heir to an important surname but lacking the means to uphold such an escutcheon, who is seduced not only by the radiant Angela Vickers, portrayed by Elizabeth Taylor at the zenith of her hieratic beauty and magnetism, but by an entire world of splendor, opulence, and glittering promises. This new universe opens before him like a blinding mirage, igniting his already latent ambition as a social climber, a compelling desire to free himself from mediocrity and to conquer, indeed, his own “place in the sun” in the firmament of a rigidly classist society yet perpetually seduced by the myth of self-affirmation.

But then, like an inescapable shadow from the past, the harsh reality embodied by Alice Tripp bursts forth – the fragile and desperate factory worker portrayed with agonizing vulnerability by Shelley Winters. His ex-girlfriend, with the announcement of an unexpected pregnancy, demands that he marry her, placing George before an unsustainable moral dilemma: the abyss of his past or the paradise promised by his future.

The young man, spurred by desperation and the prospect of losing everything, during a fateful boat trip on the lake, seriously contemplates killing the girl. It is a sequence of palpable tension, a tour de force of direction and acting, where the deafening silence and Clift's grim gaze communicate more than a thousand dialogues. Here, one notes the powerful and fascinating parallel with F.W. Murnau's expressionist masterpiece, Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans: in both films, the lake becomes a mirror of inner turmoil, a place of temptation and reflection on a capital sin, and the camera becomes the eye of conscience, immersing the viewer in the protagonist's tormented psyche. Both directors avoid moral simplification, exploring the complexity of the homicidal impulse rather than its mere execution. Yet, just when the abyss seems inevitable, George restrains himself at the last instant; his homicidal instinct appears disarmed by cowardice or a residual sense of decency.

But fate, or perhaps a form of blind and mocking justice, descends upon them: the girl, due to an unfortunate accident that leaves a disturbing ambiguity – was it pure chance, hesitation, or an involuntary push born of tension and despair? – falls overboard and drowns in the icy waters, leaving George alone with his torment and a destiny that portends to be atrocious.

During the ensuing trial, Stevens abandons the idyllic lyricism of the initial acts for a claustrophobic and oppressive atmosphere, typical of judicial noir. An implacable prosecutor, with his relentless rhetoric and thirst for exemplary justice, attempts to frame the man, building a case based on appearances and George’s unstated admissions, elevating the personal tragedy to a plane of social and media drama. The trial sequence is an indictment of the system, its rigidity and its inability to penetrate the complexity of human motivations, a legal labyrinth where procedural truth clashes with emotional and psychological truth.

An emotionally potent work, pervaded by a constant psychological tension that never slackens, not even in the most seemingly serene sequences, and enhanced by a Montgomery Clift who is not only at the peak of his artistic career here, but embodies with rare intensity the inner turmoil of a lost soul. His performance is a masterpiece of subtlety and silent expressiveness, capable of communicating George’s moral ambiguity and vulnerability with a simple glance, a nervous twitch, a posture curved under the weight of an unbearable burden. His on-screen chemistry with Elizabeth Taylor is electric, rendering their romantic idyll a vortex of desire and damnation, a forbidden dream whose attraction is palpable, almost painful.

Although Stevens is more interested in the moral implications and universal resonance of the story itself, rather than in crafting meticulous and comprehensive portraits of every single character involved (in this, it must be said, partially deviating from Dreiser, who in his monumental work depicted with surgical efficacy the psychological and sociological profile of every actor in the tragedy), the result is a work of rare depth, which inevitably impressed audiences of the time and left an indelible mark. The criticism of the kiss scene between Clift and Taylor was notable, judged “obscenely long” by Puritanical standards and the restrictions of the Hays Code of the era. A kiss that, far from being a mere romantic effusion, became a true cinematic manifesto: Stevens used cross-dissolves and extreme close-ups to extend it beyond conventional limits, transforming it into a metaphor for total fusion, for overwhelming desire that obliterates the external world and condenses the entire fatal trajectory of George’s passion. That scene, so audacious in its duration and psychological intensity, was a triumph of direction and editing that, while not literally breaking the rules of censorship, challenged its spirit, communicating a sensuality and emotional transport that went far beyond mere representation, effectively pursuing the director’s objective: to immerse the viewer not only in the plot, but in the emotional and moral vortex that is its true beating heart, rendering A Place in the Sun an enduring classic, still capable of making us question the temptations of success and the dizzying heights of desire.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...