A Trip to the Moon

1902

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

In the early days of a peculiar expressive medium called “cinematography,” when audiences were still content with the Lumière brothers' "animated views" – simple, yet fascinating, documentations of daily reality – the French director, illusionist, and actor Georges Méliès burst onto the scene, exploring with unprecedented audacity the potential of this groundbreaking technological novelty. His "Star Film" did not aim to replicate the world, but to recreate it, to shape it according to the logic of dreams and fantasy, giving birth to works that, like Le Voyage dans la Lune, proved visionary and surprisingly modern in concept, anchoring the nascent art to a future of storytelling and spectacle.

The universe of A Trip to the Moon does not feed solely on Jules Verne's daring intuitions, although the influence of his From the Earth to the Moon is palpable in the ingenious lunar cannon and the concept of a bold exploration. Méliès draws heavily from a much vaster and more layered wellspring of popular culture of his time: not only proto-steampunk science fiction novels, but also fanciful illustrations, contemporary comic strips, the burlesque traditions of music-hall, and, above all, the rich heritage of fairy tales and stage magic, his first and great passion. The film is, in fact, steeped in references to the fin-de-siècle collective imagination, an era poised between scientific positivism and a persistent, almost romantic, desire for wonder. This cultural syncretism creates a fascinating bridge between a past animated by mythology and folklore and a future that, though still nebulous, promised to be saturated with discoveries and new frontiers, both technological and conceptual. Méliès, the artisan of dreams, anticipates here a trope destined to dominate the aesthetic of the fantastic for over a century.

The echo of Méliès's influence on subsequent cinema is, in fact, undeniable and pervasive. It's not just about techniques or visual tricks, but an entire philosophy of cinema as a 'dream factory'. Directors like Georges Lucas, whose Star Wars saga is permeated by a sense of fairytale adventure and a celebration of the marvelous, and Terry Gilliam, undisputed master of visual surrealism and eccentric set designs (think of Brazil or The Adventures of Baron Munchausen), have openly acknowledged their debt to the French filmmaker. But his shadow stretches far beyond: from the audacious use of color (Méliès had his films hand-colored, a practice that foreshadowed the aesthetic of Technicolor) to the first forays into the science fiction and fantasy genres, and even to the very idea that cinema could be a vehicle for pure escapism, for worlds that exist only in the creator's mind. His creative approach, based on illusion and wonder, and his pioneering spirit continue to inspire not only new filmmakers eager to explore the boundaries of imagination, but also entire generations of viewers, who, in every special effect, in every cinematic journey into the unknown, rediscover an echo of the primordial Mélièsian wonder.

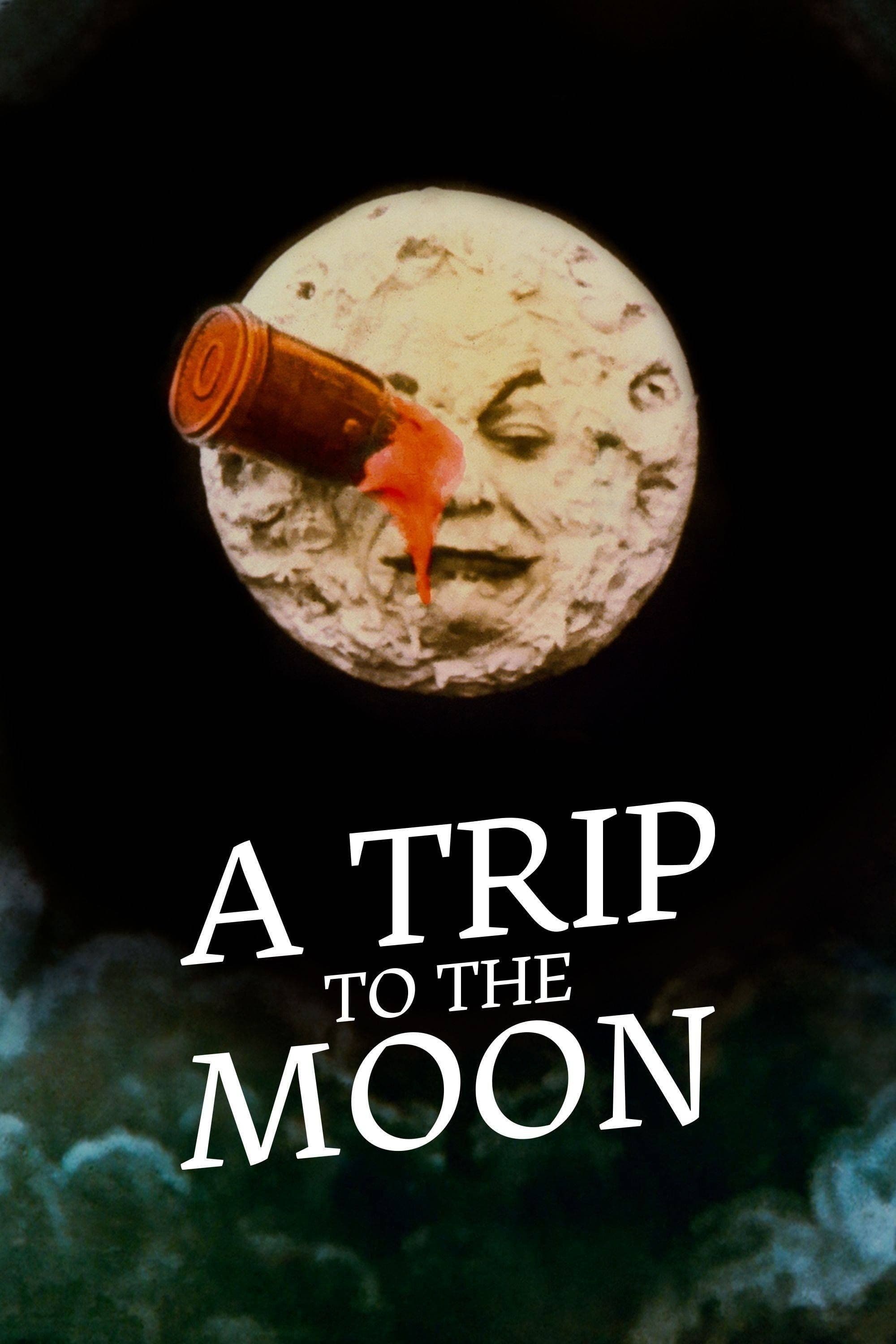

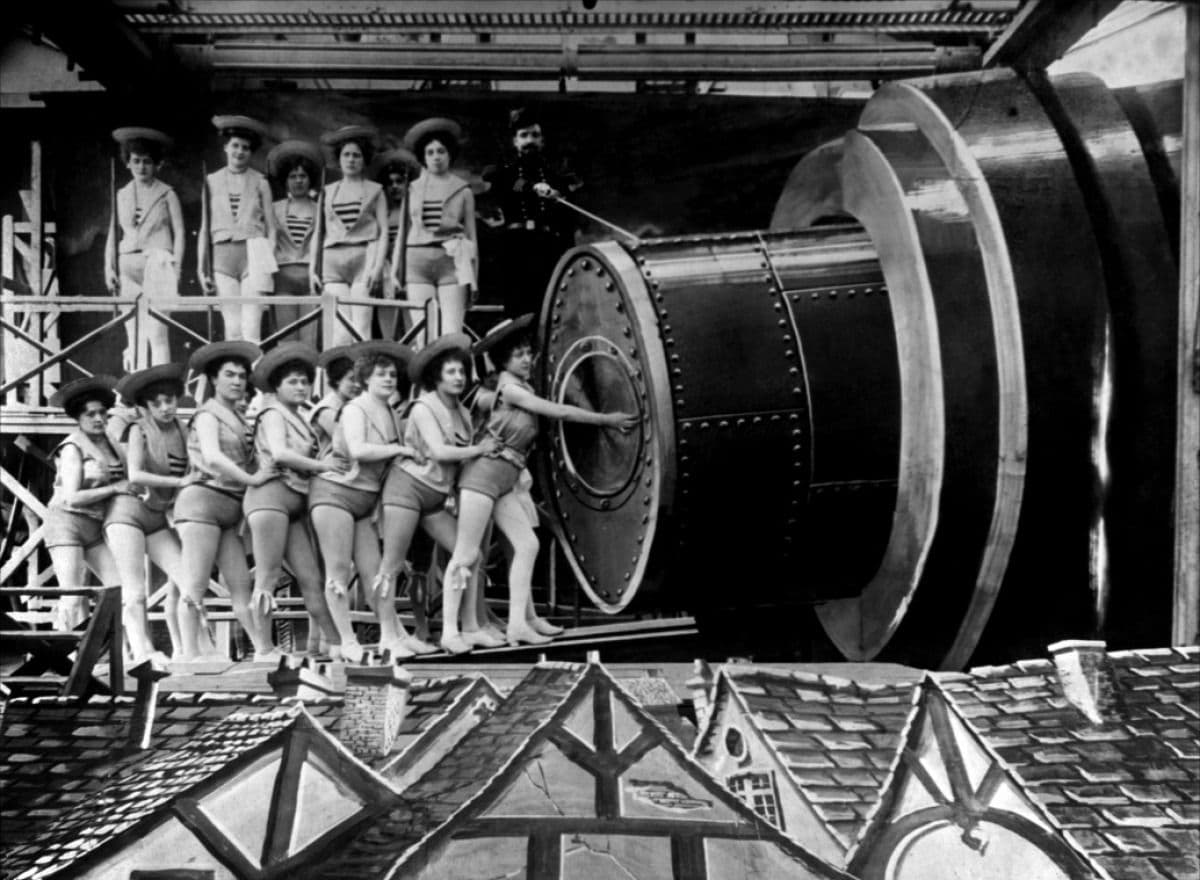

Drawn from a tale that freely draws on the Vernean imagination, the narrative unfolds with a dreamlike logic, typical of the Belle Époque. The story follows an eccentric group of astronomers, led by Professor Barbenfouillis, who, in a surge of scientific ambition and pure visionary madness, decide to reach the Moon. Their means of transport? A capsule-shaped projectile, fired from a gigantic cannon. The iconic image, now etched into collective memory, of the spaceship directly hitting the eye of the anthropomorphic Moon, giving it a surprised and pained look, is one of the most ingenious and recognizable moments in the entire history of cinema. Once they reach their destination, our intrepid travelers encounter a hostile and bizarre people: the Selenites, insectoid creatures that dissolve into smoke when struck. These inhabitants of the satellite are dominated by a tyrannical king who, echoing the imperialist and colonial fears of the era, wants to imprison the Earthlings and enslave them, only to be overcome by cunning and technological superiority (an umbrella can be a deadly weapon!).

But beyond its simple, yet fascinating, narrative, A Trip to the Moon is a kaleidoscope of symbolic meanings, an allegory in motion. The journey to the Moon, a supreme metaphor for the quest for the unknown, is charged with a Promethean ambition, the discovery of new worlds that are not only unexplored geographical spaces, but also inner dimensions, limits of human knowledge to be overcome. It is the epic of man who dares to challenge the heavens, who pushes beyond the known to embrace the ineffable, and herein lies its lasting power. The film captures the spirit of an era, the fin de siècle, projecting it towards a future of infinite possibilities, where science and fantasy merge into a single, intoxicating quest. Subtly, in every hand-painted frame and every stage trick, the unparalleled talent of the director shines through in best rendering not only the caricatured expressions on the actors' faces (often Méliès himself and his company), but also the alien, fantastical, and at the same time unsettling landscapes, populated by giant mushrooms and dazed creatures. The dynamism of the journey is rendered through an uninhibited use of the camera that, for the first time so systematically, does not merely record, but becomes an instrument of transformation and magic: from cross-dissolves to quick cuts, from forced perspective effects to stop-motion that makes objects and characters appear and disappear in the blink of an eye. It is a beautiful and unforgettable beginning not just for a film, but for the entire epic of cinema as the art of wonder, a journey that, thanks to this unparalleled pioneer, poured forth a cornucopia of Wonders upon all who embarked on it, revealing a narrative and visual potential previously unimaginable.

To Georges Méliès, the man who built the first glass-roofed film studio in Montreuil – a veritable dream workshop – we owe, without hyperbole, truly everything. He was an artisan driven by an implacable curiosity and an insane, almost maniacal, desire to experiment, which led him to discover and shape many of the cinematic techniques that still form the backbone of film grammar today. From "masking" (the primitive matte shot that allowed multiple images to be combined into one, creating illusions of vast worlds or fantastic creatures) to the "single shot" (stop-motion or trick photography that animated inanimate objects or made characters disappear in a flash, inherited from his practice as an illusionist), up to editing understood not merely as a concatenation of scenes, but as a narrative tool capable of altering spatial and temporal perception. Méliès, in an era when the camera was often static and editing almost non-existent, intuitively grasped the power of the cut to create surprises and illusions, to guide the viewer's eye through a labyrinth of wonders.

Méliès, with his conjurer's mind and artistic sensibility, immediately understood the evocative and almost hypnotic power of moving images. Every single shot, often taken from a fixed perspective reminiscent of a theatre stage but with unprecedented depth and richness, was meticulously planned. From elaborate sets, often painted with breathtaking prospective backgrounds, to eccentric and imaginative costumes that transformed actors into creatures from another world, everything contributed to creating a fantastical universe that was, in its own peculiar way, believable. It was not about reproducing reality, but about giving form to dreams, making them tangible. It is no coincidence that the sequence of the spaceship crashing into the Moon's eye has become an icon of world cinema, an image that has transcended time and cultures, marking the imagination of entire generations of viewers and filmmakers, a true visual archetype of discovery and the impact of the new on the old.

In this short, sparkling film of just fourteen minutes (in its original, colored version), all his Art is condensed, all his spontaneous and contagious wonder in approaching this new world of celluloid. Méliès, the great storyteller, the heir to Scheherazade but with a camera instead of words, derived wondrous stories from it to narrate to his audience, no longer just words or stage tricks, but a symphony of moving images. He thus demonstrated, with the force of irrefutable evidence, that cinema is a universal language, capable of overcoming every cultural and linguistic barrier, of touching the deepest chords of human imagination. Images, just like primordial emotions, have the intrinsic power to communicate ideas and suggestions directly and immediately, without need for translation. A Trip to the Moon is not just a film; it is the beginning of everything, the celluloid big bang that gave rise to an infinite universe of narratives, a portal to illusion, wonder, and, above all, the infinite possibility of cinematic dreaming. Its light continues to shine, a guide for anyone who dares to look at the stars.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...