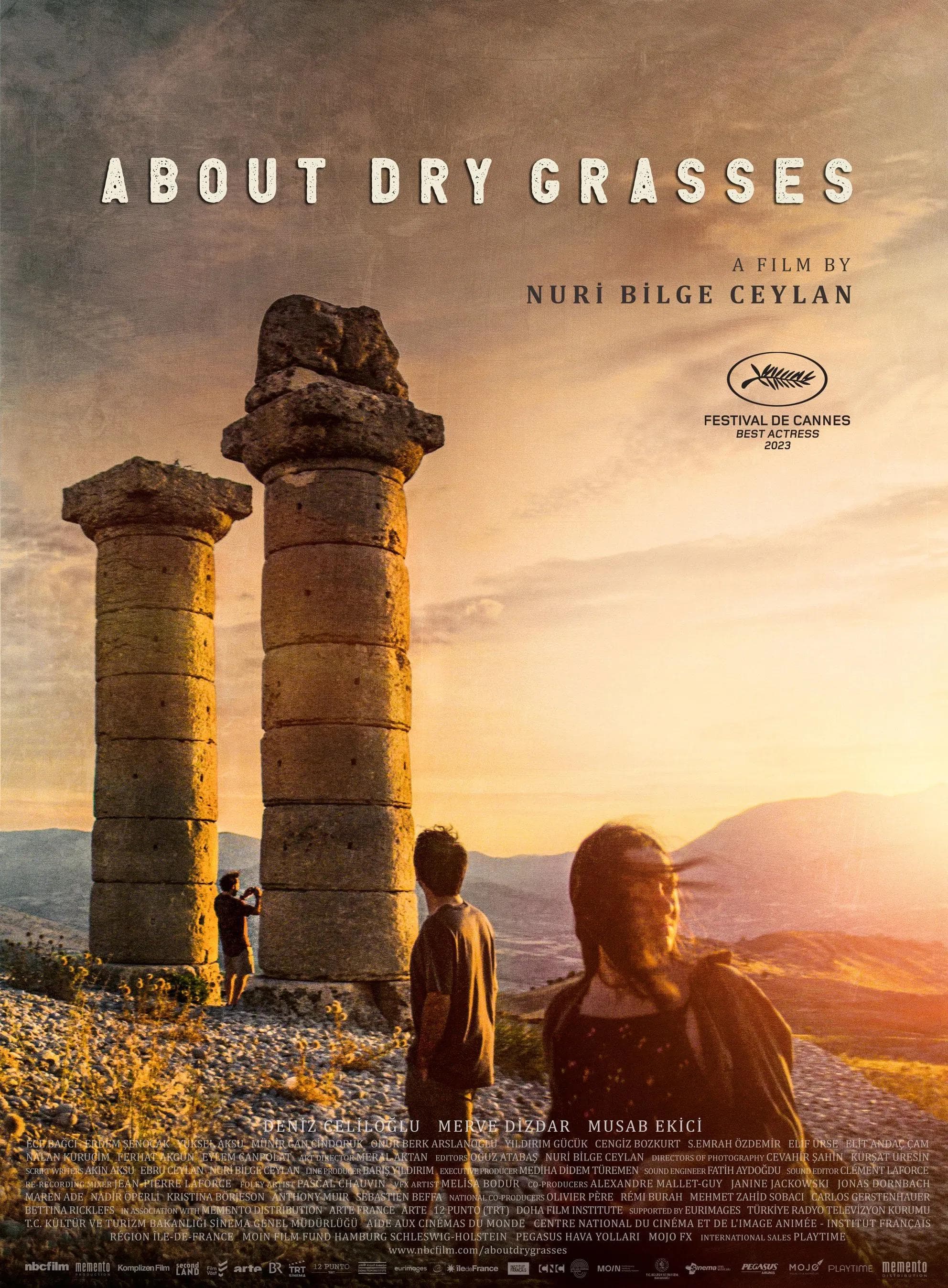

About Dry Grasses

2023

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(2 votes)

Director

A young teacher, Samet, hopes to be assigned to the coveted Istanbul after compulsory service in a small, remote village in eastern Anatolia, buried for months under a blanket of snow and silence. This seemingly simple premise is the starting point for this work by Nuri Bilge Ceylan, a film that, like its landscape, is at once of boundless beauty and almost unbearable harshness. Tale of Two Seasons (the original title, Kuru Otlar Üstüne, “On Dry Grass,” is much more effective) is not a coming-of-age story, nor is it a conventional social drama. It is an immersion of over three hours into the winter of an antihero's soul, a novelistic elegy on boredom, cynicism, and the desperate, and perhaps futile, search for meaning in a place that seems to have been forgotten by God and man.

Nuri Bilge Ceylan is undoubtedly the most important auteur in contemporary Turkish cinema, a director who has created a highly personal language capable of dialoguing with the great European masters while remaining deeply rooted in the geography and psyche of his homeland. His cinema is a cinema of duration and patience, nourished by torrential dialogue and meaningful silences. While his use of landscape as a mirror of the soul and his exploration of existential ennui bring him closer to Michelangelo Antonioni, his true literary soul is that of Anton Chekhov. Samet, the protagonist, is a purely Chekhovian character: a cynical and frustrated intellectual, trapped in the provinces, who feels superior to his surroundings but is incapable of making a move that would free him from his own apathy. The long conversation scenes, often around a table, where politics, art, and life are discussed with a mixture of idealism and resignation, seem to come straight out of a play by the great Russian playwright. Ceylan, like Chekhov, has an extraordinary ability to capture the subtlest nuances of the human soul, the comedy and tragedy that lie behind the apparent banality of everyday life.

Ceylan's genius, and what elevates the film to a masterpiece, lies in his refined and at times unsettling meta-textual awareness. Samet is an amateur photographer. His camera is his shield, the filter through which he observes a reality he does not really want to touch. He photographs the faces of the villagers, particularly his students, transforming them into aesthetic subjects, into works of art. It is a way of creating distance, of exercising a form of control over a world that makes him feel powerless. The film is punctuated by these shots, magnificent portraits that freeze life and beauty in an instant, contrasting with the slow and stagnant main narrative. But Ceylan pushes this reflection on the relationship between reality and representation to a breaking point in a memorable and daring scene. In the middle of a tense confrontation in his apartment, Samet stands up, walks toward a door, and instead of entering another room, literally walks off the set. We see him walking among the lights, cables, and crew members in a film studio. It is a Brechtian gesture of unheard-of power, a deliberate tear in the veil of fiction. In that moment, the director tells us: “Remember that you are watching a film. This character is an actor, this room is a set, this pain is a construct.” This breaking of the fourth wall is not an intellectual affectation; it is a philosophical move that is inextricably linked to the psychology of the protagonist. Samet is a man who feels like an actor in his own life, a character trapped in a script he did not write. Ceylan's choice to show us the fiction of his work forces us to question the nature of truth, both that of the film and that of its ambiguous and perhaps unreliable protagonist.

Ceylan's aesthetic style is completed by his pictorial vision of the Anatolian landscape. His wide shots, showing tiny human figures lost in the immensity of a snow-covered plain, have the same sublime and melancholic power as Caspar David Friedrich's landscapes. These are images that speak of man's loneliness in the face of a magnificent but indifferent nature. The film is not just a “tale of two seasons”—the long, harsh winter and the brief, almost reluctant explosion of life in spring—but a profound meditation on the human condition. It is a work that asks us to look closely at the dry grass sprouting from beneath the snow, to find not a sign of death, but the stubborn and inexorable promise of another, possible season.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...