Accattone

1961

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

Pasolini's first film marks the entry into the Seventh Art of a man endowed with truly unique sensitivity and iconographic intuition. It was not a mere stylistic exercise or an appendix to his already celebrated literary works, but rather a true cinematic epiphany, the materialization of a radical and profound worldview. His prior experience as a poet, novelist, and essayist had not only provided him with a sharp pen and analytical perspicacity, but also with an almost lyrical ability to grasp the essence of things, translating it into images of disquieting beauty and cruelty. His eye, already trained to dissect society and reveal its most recondite folds in prose, here becomes an implacable lens, capable of stripping reality bare and revealing its soul.

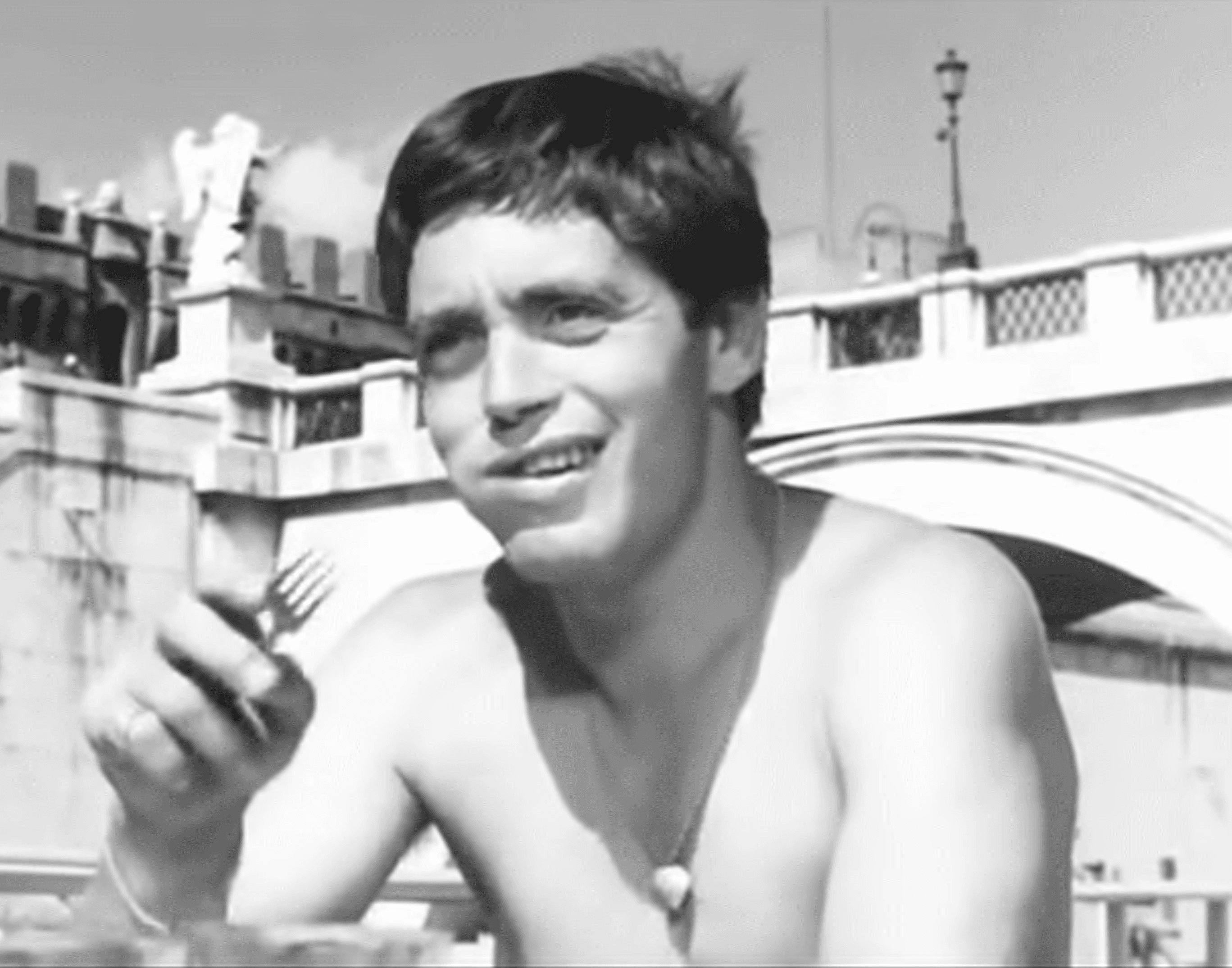

A poet behind the camera who views reality with a sociological gaze, who loves to tell the stories of a proletariat teeming with spontaneous characters voracious for life, like Accattone. It is not simple chronicle, but an anthropological inquiry into the Roman sub-proletariat of the slums, a universe on the margins that Pasolini had already explored in his narrative works such as “Ragazzi di vita” and “Una vita violenta”. These characters, far from being marginal figures, are for Pasolini the last custodians of a primal authenticity, an anarchic vitality, and a secular sacredness that bourgeois society and nascent consumerism were inexorably erasing. Their dialect, their rituals, their existence precariously suspended between theft and naive survival, are observed with a detached, almost phenomenological pity, yet always imbued with a visceral love for their desperate purity.

Accattone is a kind of parasite who lives off petty theft, with a partner he compels to prostitute for him. His is an existential wandering, living day-to-day without pretension or horizons, yet imbued with a peculiar dignity. When she is arrested, he will turn to a second woman with whom he falls in love, giving rise to a more complex and less instrumental relationship, perhaps the only glimmer of authentic emotional seeking in an existence otherwise devoted to mere instinct.

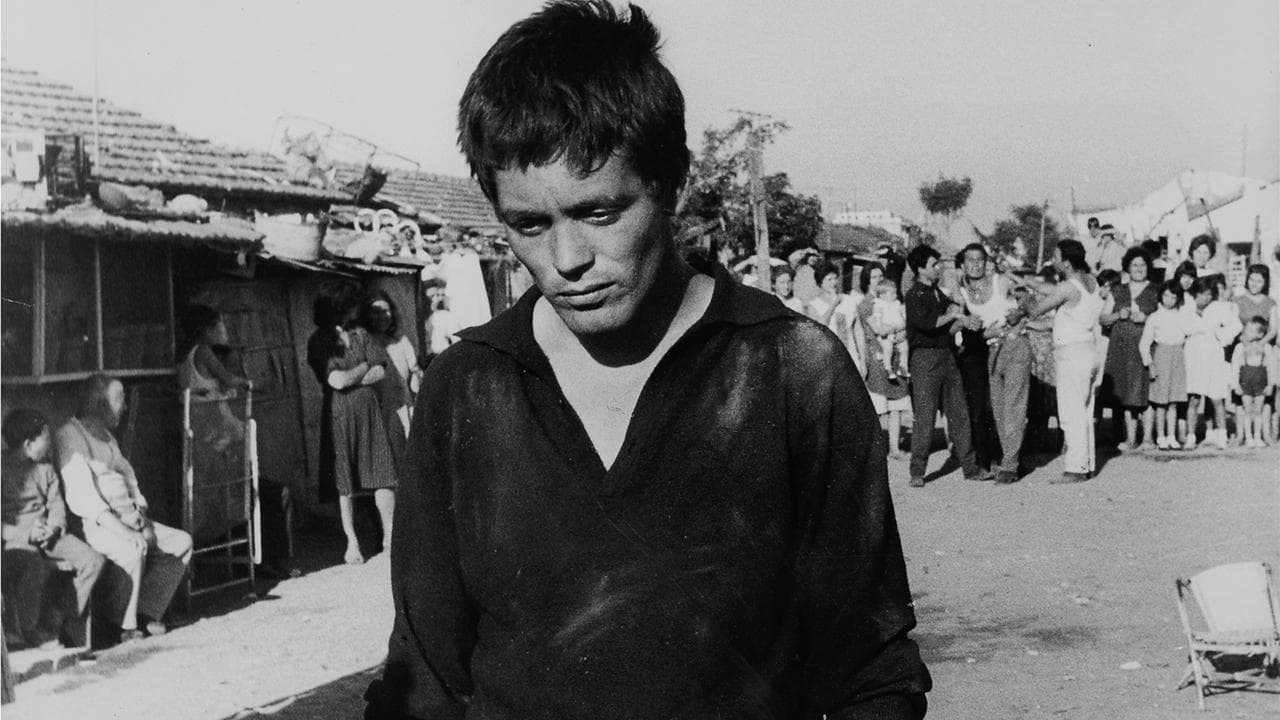

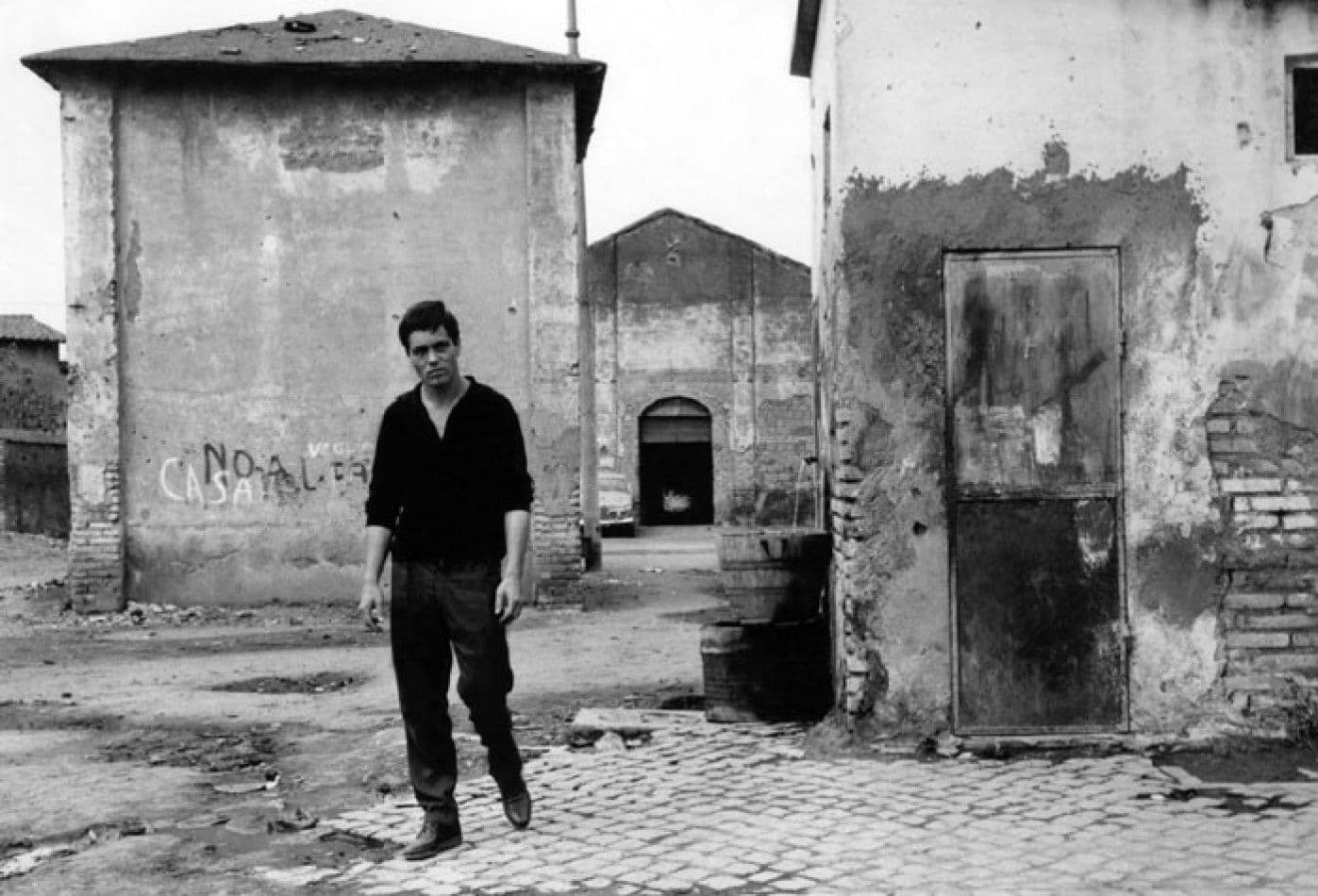

Above all, the powerful aura of this character, belonging to a chthonic, material, experiential dimension, with an ethics certainly distorted but always preferable to the hypocritical rhetoric of Rome's "respectable" middle-bourgeois class. His morality, if one can speak of morality, is not a product of social precepts but of an internal, archetypal law, sculpted in survival and overpowering, yet devoid of the false consciousness that shrouds "respectable" civilization. Accattone, with his elusive and contradictory personality, thus becomes an emblem of a vanishing world, that of pre-industrial and pre-bourgeois cultures, which Pasolini saw as a reservoir of authentic values, contrasted with the moral and cultural degradation brought about by the Italian "economic miracle".

A work that embodies the lesson of Neorealism and stages life in the most remote and squalid outskirts as it is, without pretense, without any kind of filter. But it transforms it, elevates it, thanks to daring stylistic choices and an aesthetic that transcends mere documentation. Pasolini, more than anyone else, succeeded in representing reality in its rawness, but he did so by imbuing it with an almost sacred, at times epic, dimension. The sublime use of Johann Sebastian Bach's music, dissonant yet extraordinarily effective in contrast with the brutalization of the peripheries, confers an unexpected solemnity upon the images, a metaphysical breath that elevates misery to classical tragedy. This daring juxtaposition – the squalor of the Roman slums commented on by Baroque fugues – is not a mere provocation, but a profound declaration of intent: Pasolini did not merely show the world, but intended to reveal its intrinsic, lost religiosity, its beauty in dissolution.

Some contemporary critics harshly criticized the nonchalance with which religious themes were approached in the film, treated more or less veiledly by Pasolini as mere background, as a dialectical interlude to his narration: in our opinion, it is entirely out of place to discuss this (Accattone is certainly not about this, nor is religion relevant in this film) and indeed, those who did so somehow completely misrepresented the semantic heritage of the work. It was not at all a background element, but a structural one, although not in its orthodox sense. Religiosity in Pasolini is an ontological disquiet, a search for the sacred in the profane, an obsessive fascination with the archetype and myth. Pasolini's "Christ" is not that of sacristies, but a most human and earthly Christ, who can find incarnation in a suffering sub-proletarian. Accattone's death, not coincidentally, has been read by many as a secular crucifixion, a misunderstood sacrifice that seals the fate of a pure and condemned world. Therefore, religiosity is not an accessory detail, but the substrate upon which his most desperate and lucid vision is grafted: the realization that the vital force, the pagan purity, and the sacredness of primitive man were dying, overwhelmed by bourgeois homogenization and rationalization. The film is, ultimately, a lament for this loss, a bitter elegy for that "firefly" which, as Pasolini would later write, was dying out.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...