Goldfinger

1964

Rate this movie

Average: 4.50 / 5

(2 votes)

Director

Probably the only film in the 007 series that fully captures Ian Fleming's British sense of humour and successfully translates it onto the screen. It's not just a matter of biting wit or dry humour, but of a peculiar worldview that permeates every shot: a sophisticated irony that serves as a bulwark against chaos, an elegant disillusionment that makes global threats less grim and, dare I say, more manageable. Where other chapters of the saga, even with the same Connery, would sometimes veer towards simpler action or excessive gravitas, Goldfinger maintains an almost ethereal lightness, a precarious yet sublime balance between the seriousness of the stakes and the pure, almost anarchic, delight of the staging. It is the film that consolidates the Bond paradigm, elevating the agent from a mere protagonist of spy stories to a pop icon capable of defining an era.

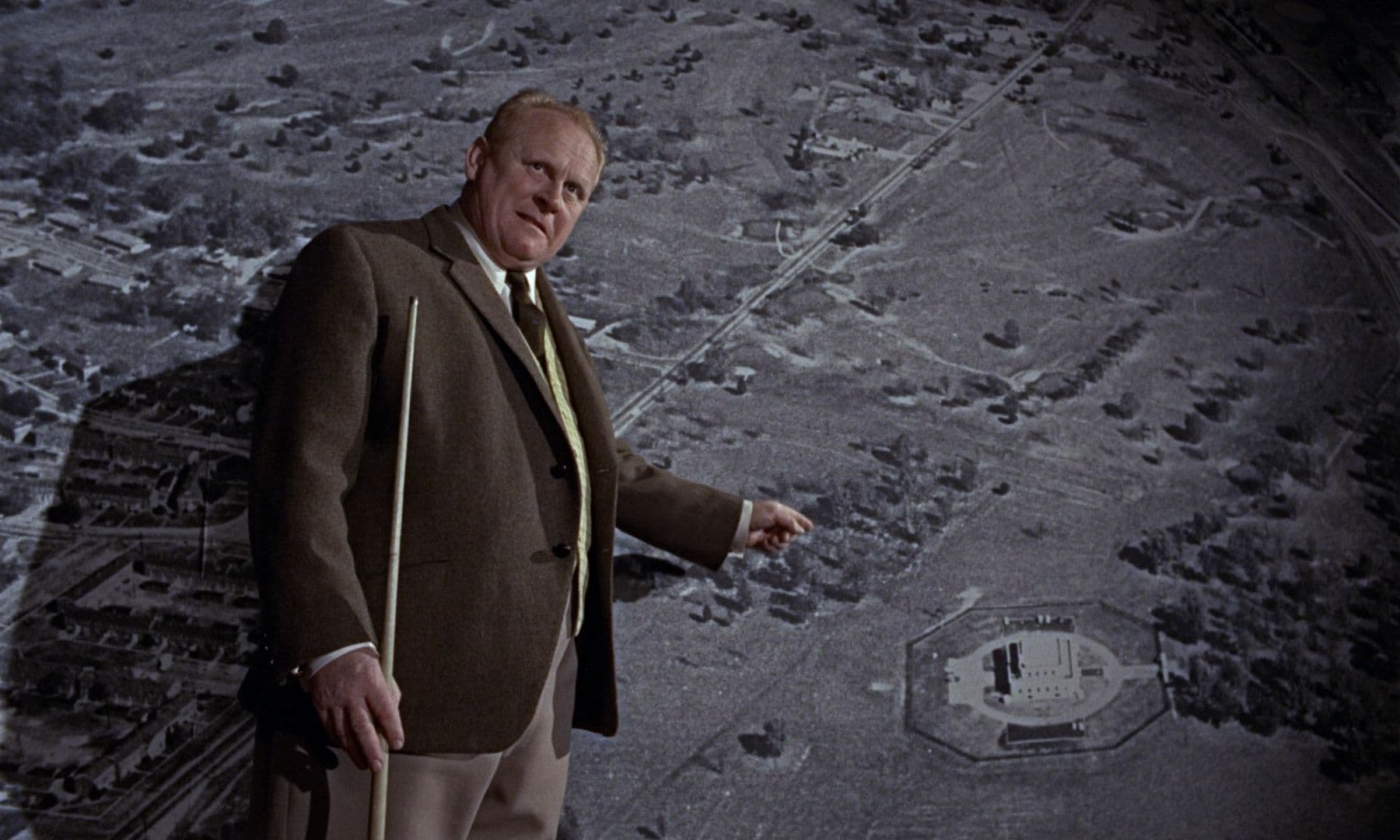

James Bond is grappling with a shady gold magnate who intends to revalue his assets by attacking Fort Knox's gold reserve and rendering it unusable. Auric Goldfinger is not just any villain; he is an archetype, a magnified representation of post-war capitalist megalomania, a man whose obsession with the yellow metal transcends mere greed to culminate in a sort of artistic perversion, a desire to mold the global economic reality in his own image. His distorted but grandiose vision of triggering a "gold crisis" is not just a narrative mechanism, but a keen satire of the geopolitical anxieties of the period, in a decade when global economic stability was still a delicate balance. His plan, so audaciously simple in its destructive conception, makes him as memorable as his henchmen, from the unforgettable Oddjob and his deadly reinforced-brim hat, to the controversial yet untamed Pussy Galore, a female figure who challenges and simultaneously reinforces certain Bondian stereotypes, adding a touch of pulpy audacity that at the time raised some eyebrows, but which today we recognize as an integral part of her subversive charm.

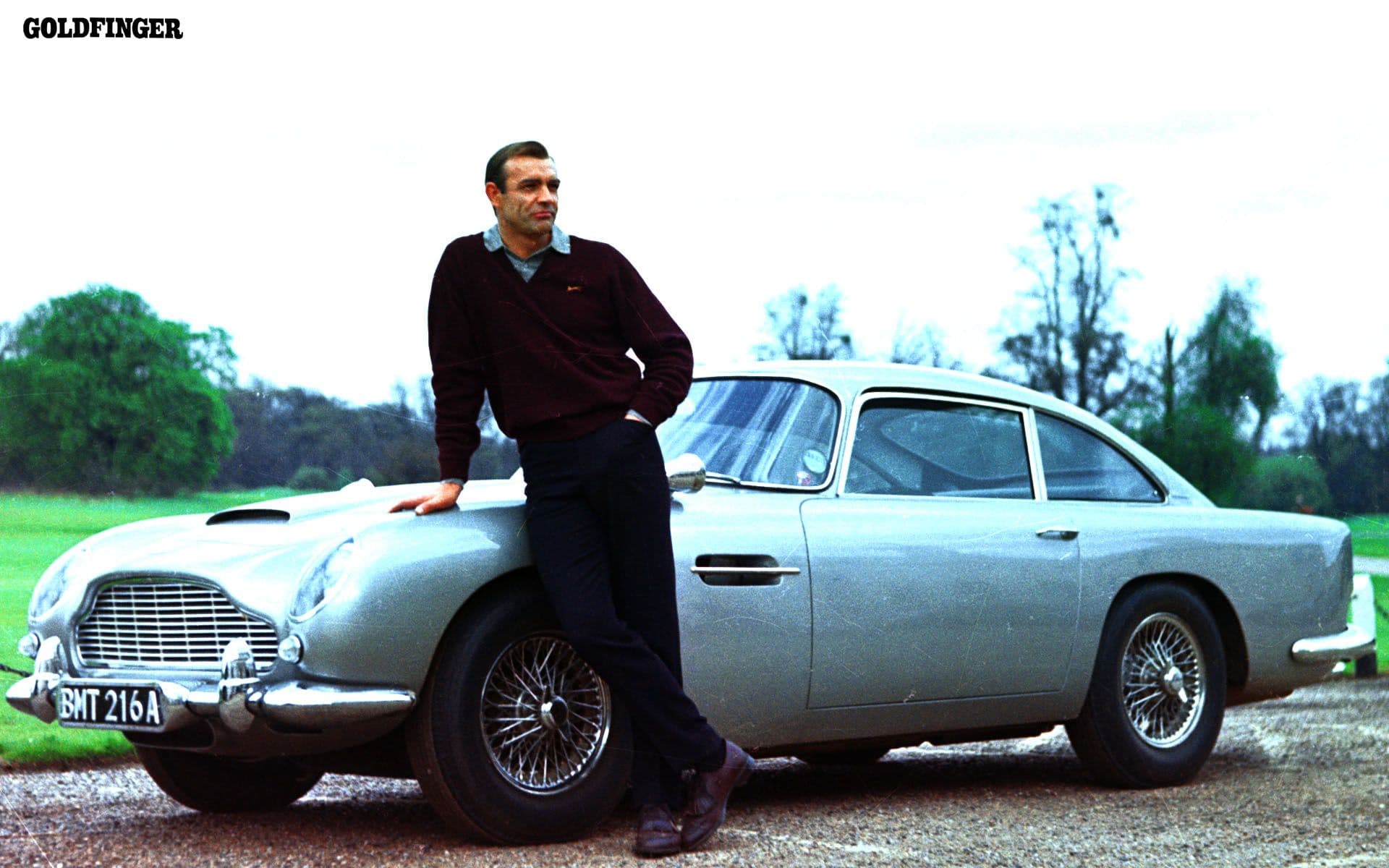

Some scenes are memorable, especially the golf match between Goldfinger and Bond, with the fraudulent ball substitution ("you played a ball that wasn't yours at the 18th hole") and the resulting strained gags between the two contenders. This sequence is a microcosm of the entire film: an intellectual and psychological duel disguised as an innocent pastime, where sporting elegance masks brutal competition. But Hamilton's narrative acumen doesn't stop there: how can one not mention the celebrated laser scene, whose dialogue ("No, Mr. Bond, I expect you to die!") has rightfully entered the pantheon of cinematic quotes, forever defining the perfect villain's cold and disdainful attitude. Or the sequence in the stable, with Bond immobilized and the palpable threat of Pussy Galore and her 'pilots'. Every frame exudes a timeless 1960s aesthetic, a riot of gadgets that are never ends in themselves but always functional to the plot and, above all, to the construction of the Bond myth, elevating industrial design to an art form and luxury to a manifesto of an era.

Hamilton perhaps finds the authentic Bond with a light and ironic direction, tinged with wit and wonder: the set design innovations do not become a pretext to build a story but become an integral part of it, not obstructing its narrative development. Guy Hamilton's touch, in his first approach to 007, is that of a meticulous craftsman and a visionary at the same time. He understands that Bond's success lies not only in action but in stylistic exaggeration, in the creation of a polished yet tangible universe. Crucial, in this, is the contribution of Ken Adam, a production designer whose creative genius literally invented Bondian iconography: from the futuristic interiors of Goldfinger's headquarters with its deadly traps, to the laser room, and the imposing Fort Knox redesigned for the epic finale. Adam doesn't simply build sets, but environments that are characters in their own right, architectural elements that narrate and amplify the drama, transforming spaces into veritable arenas for ingenuity and destruction. His 'total design' approach elevates Goldfinger from a simple thriller to an exercise in style, a visual symphony that blends modernism, a hint of kitsch, and a good dose of futuristic fantasy, setting a standard for the modern blockbuster.

A final nod to Connery's mischievously serene demeanor, the one and only true 007 agent to ever grace a set. His performance is a masterpiece of subtlety and charisma. It's not just the athletic physicality or the quick wit; it's the almost alchemical balance between the killer's latent brutality and the gentleman's sophistication, between sardonic irony and a certain romantic fatalism. Connery embodies Bond not just as a character, but as a philosophy, an attitude: his gaze, capable of shifting from seduction to coldness in an instant, his proud walk, the way he handles a gun or a vodka martini. He is the Bond who defines the archetype, the one to whom all successors will inevitably be compared. His 'mischievously serene demeanor' is not a mere expression, but the key to understanding a character who confronts global threats with a raised eyebrow and a sly smile, suggesting that, deep down, the universe is a stage for his adventures, and life a game to be won with style. Goldfinger is not just a film; it is the apex of an era, a manifesto of elegance and adrenaline that continues to influence cinema and the collective imagination, a work that has forever sculpted the face, soul, and impeccable suit of James Bond.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...