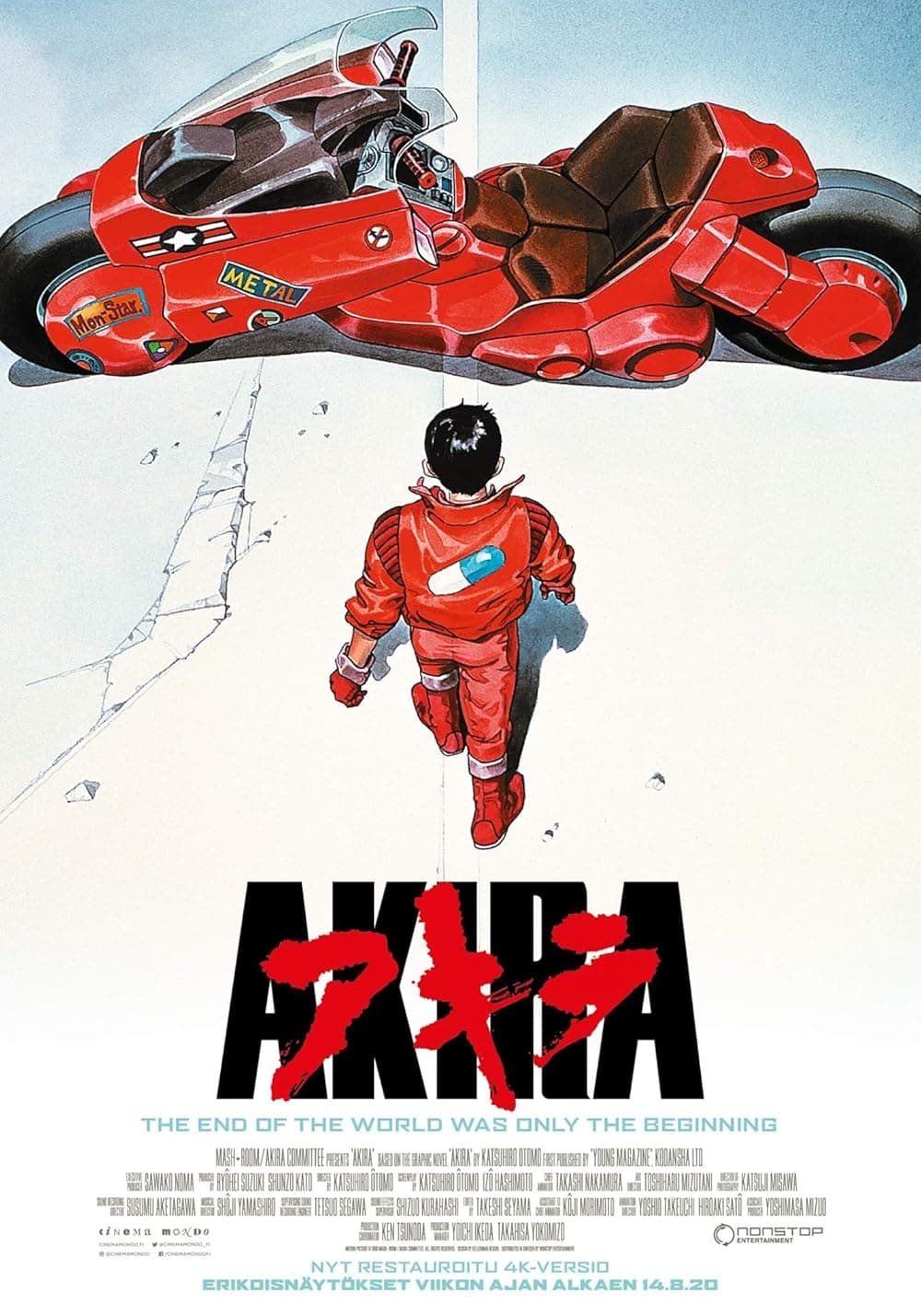

Akira

1988

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

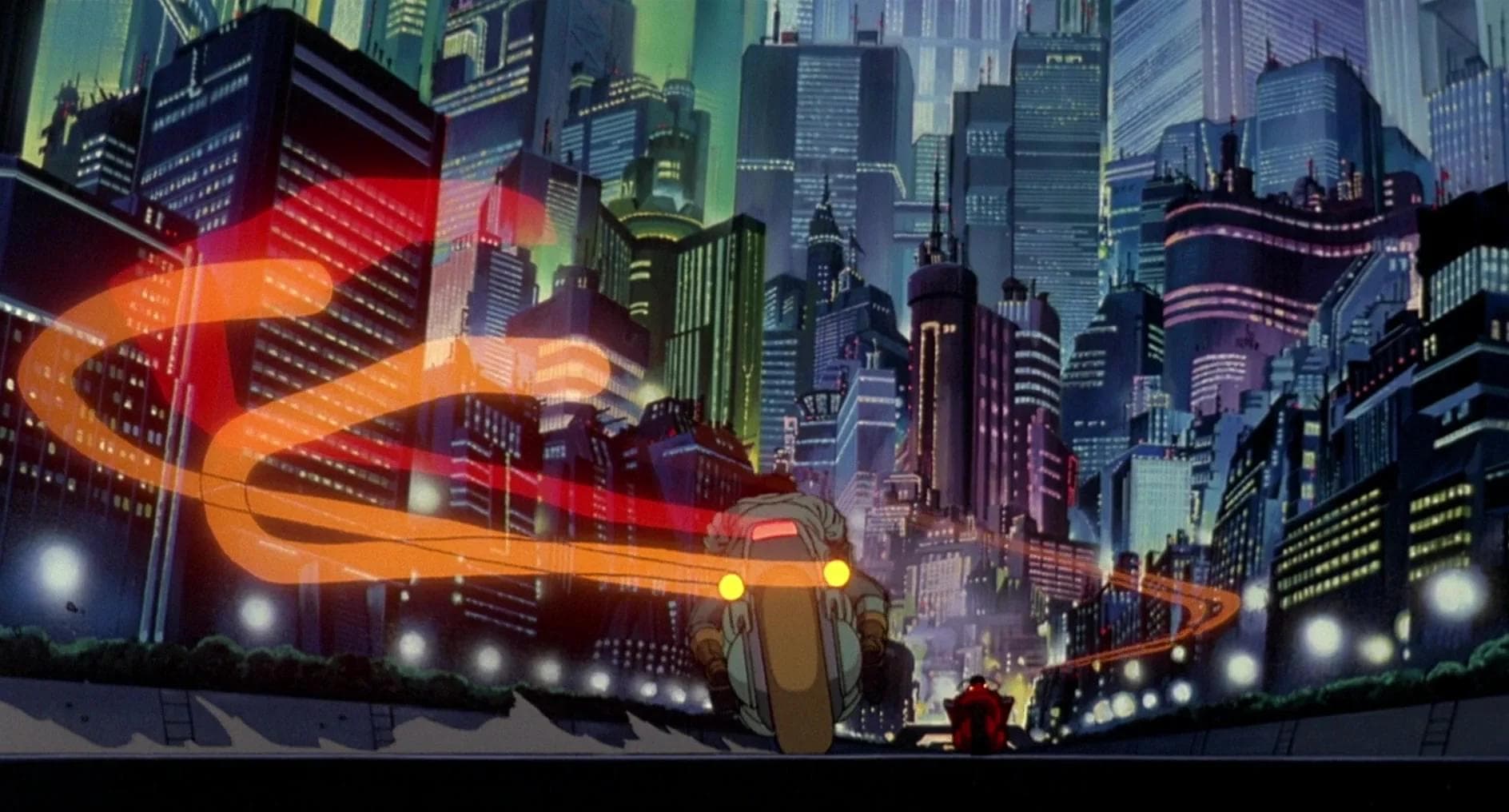

Akira is the seismic event that in 1988 destroyed the Western perception of animation as a harmless pastime for children, and on whose smoking ruins the imagination of an entire generation was built. Katsuhiro Ōtomo's work has not aged a day; on the contrary, time has only made its prophetic scope and its astonishing, almost arrogant technical mastery more evident. To talk about it is to talk about a symphony of neon, concrete, and mutated flesh, a monster of a work that took cyberpunk, infused it with Japan's nuclear unconscious, and projected it into the future, marking a point of no return.

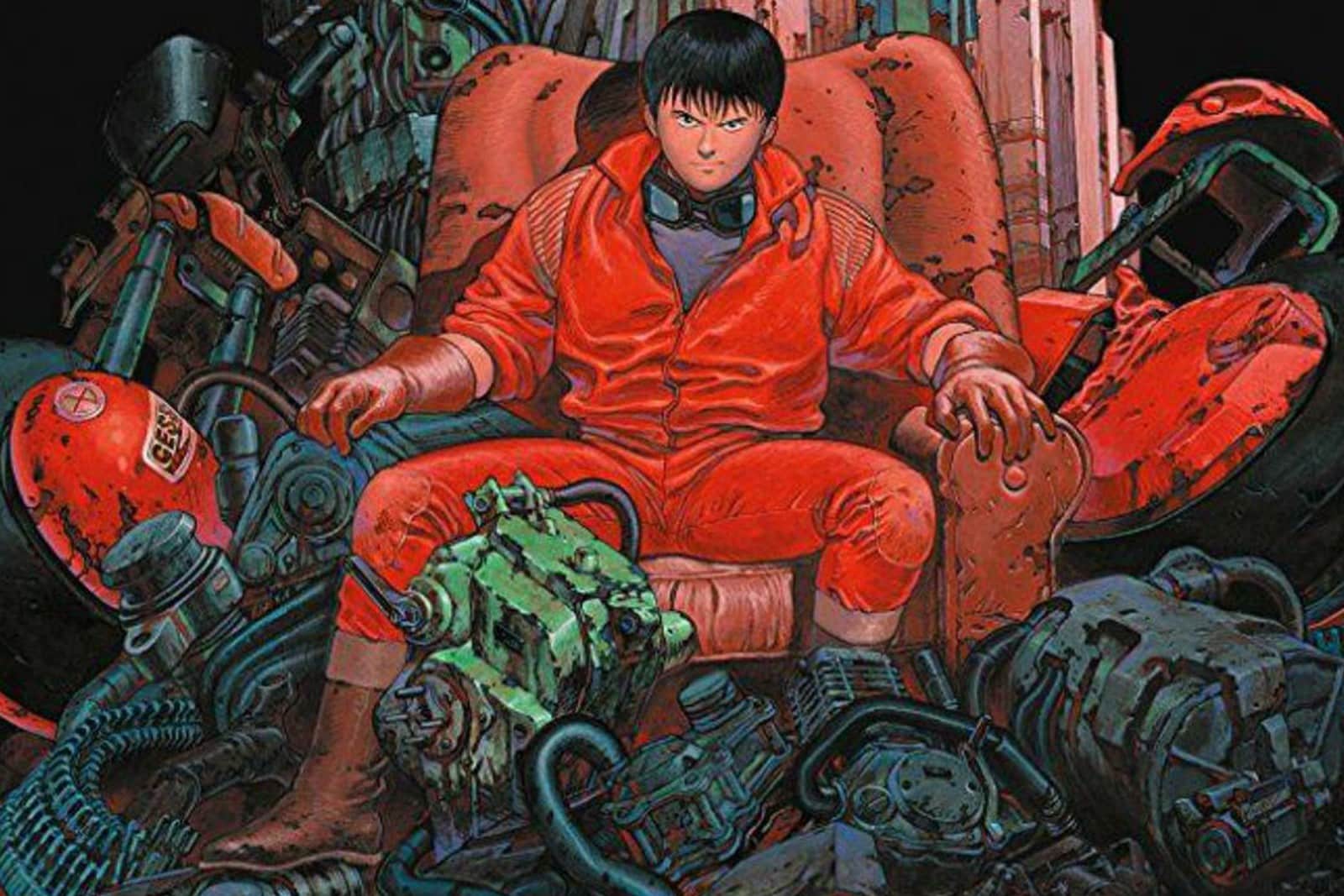

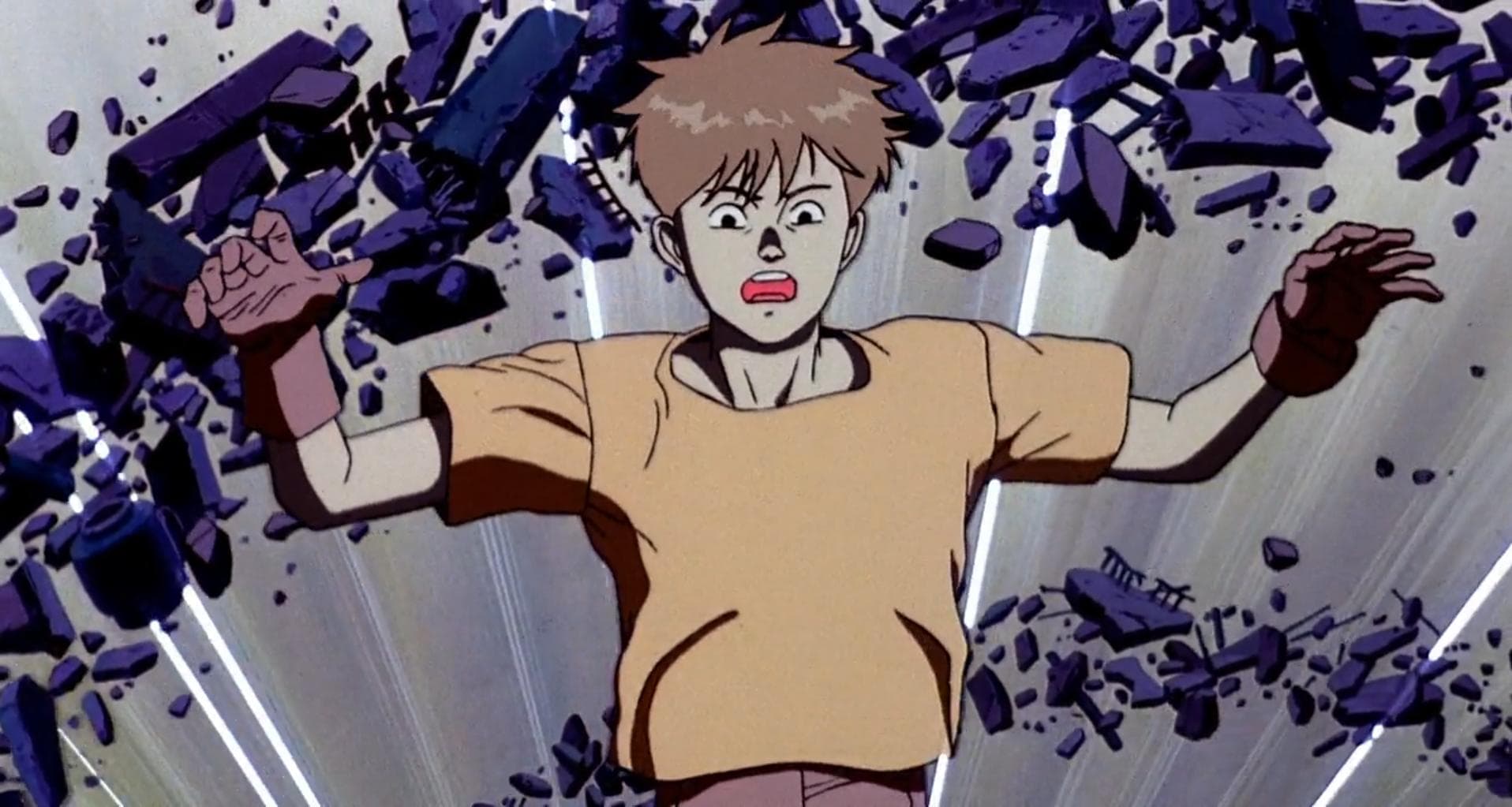

The story throws us into 2019, in a Neo-Tokyo seething with violence and social unrest, thirty-one years after a mysterious explosion sparked World War III. In this sprawling, decadent metropolis, we follow the adventures of a gang of teenage bikers, the Capsules, led by the charismatic and arrogant Kaneda. His best friend, and at the same time his most insecure and resentful subordinate, is Tetsuo. During a nighttime clash with a rival gang, Tetsuo has a fatal encounter with a decrepit-looking child, an esper who has escaped from a secret government laboratory. The incident awakens latent psychic powers of unimaginable potency in Tetsuo. Captured by the military, the boy becomes a guinea pig for experiments that amplify his abilities to a point of no return. His long-repressed inferiority complex explodes into a delirium of omnipotence, transforming him from victim to vengeful and uncontrollable deity. As Tetsuo wreaks havoc on the streets of Neo-Tokyo, Kaneda, along with a group of anti-government terrorists, embarks on a desperate mission to stop his friend, discovering the terrifying secret the government is trying to hide: an entity of pure energy called Akira, the cause of Tokyo's original destruction.

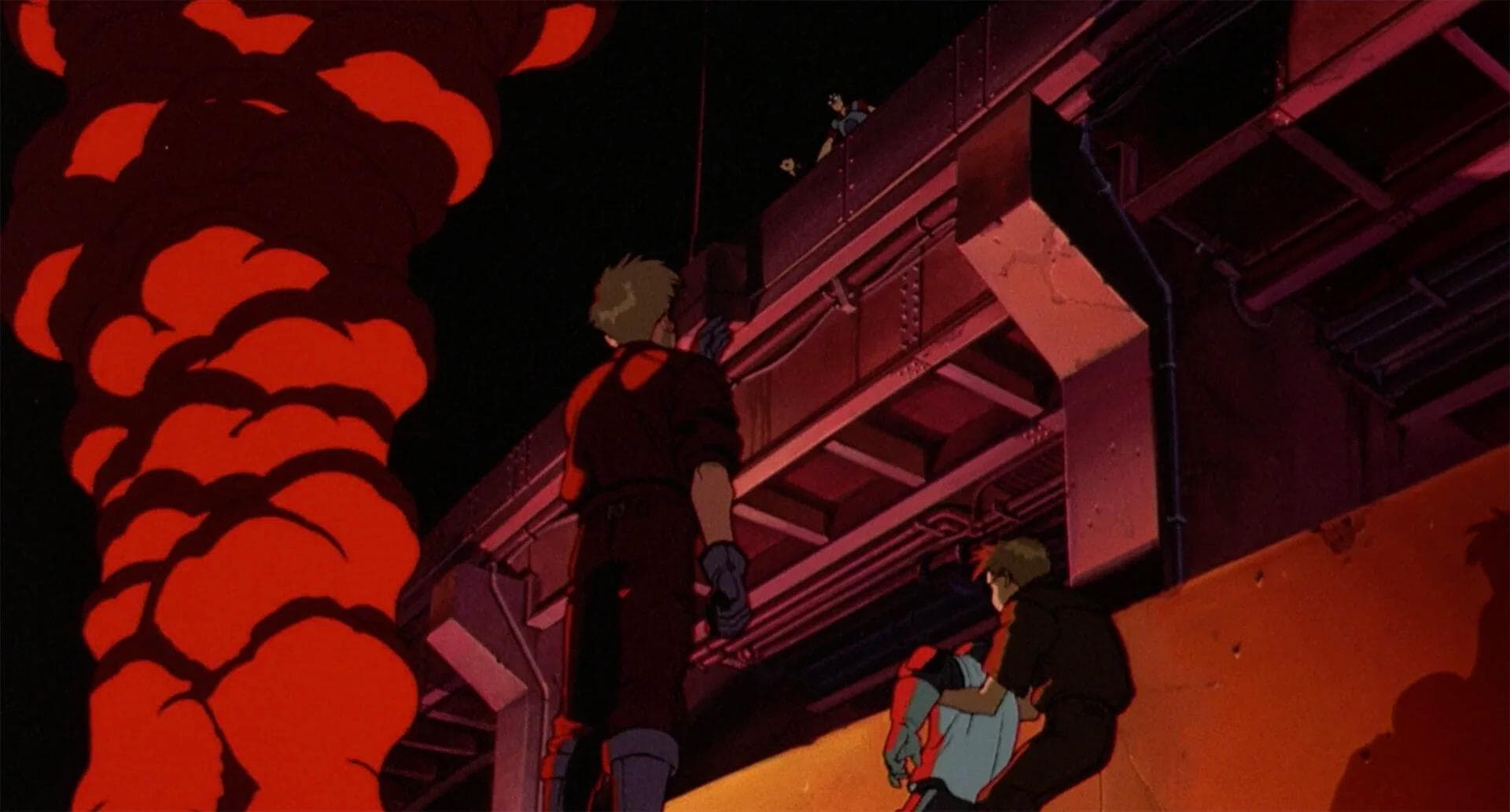

Cyberpunk, as a literary genre, had already found its prophet in William Gibson with Neuromancer a few years earlier. But it is with Akira that cyberpunk finds its visual bible, and it does so by choosing the seemingly least suitable medium: animation. Ōtomo fits into this landscape by carrying out a revolutionary operation. While American cyberpunk focused on cyberspace and the cold abstraction of data, Ōtomo brings the battle back to the most primordial place: the body. His is a visceral biopunk, where technology does not create artificial intelligence, but unleashes latent psychic powers, transforming adolescence itself, with its anger, alienation, and hormones, into a weapon of mass destruction. The aesthetics are simply dazzling because they stem from an almost pathological obsession with detail. Unlike limited animation, Ōtomo demanded that every single frame be dense with information and movement. Neo-Tokyo is not a backdrop, it is a living, diseased organism, with its arteries of light, its concrete organs, and its tumors of social decay. The hand-drawn light trails of Kaneda's motorcycles, the almost unreal fluidity of the explosions, the use of over two thousand colors at a time when a few hundred was the norm: this was not innovation, it was a declaration of war on the status quo of animation.

The post-apocalyptic genre, of course, did not begin with Akira, but Ōtomo's film became one of its absolute pinnacles, redefining its language for years to come. His work is rooted in a past that includes the rural desolation of Mad Max and the urban anarchy of John Carpenter's cult classic Escape from New York. If Carpenter showed us a Manhattan transformed into an open-air prison, Ōtomo shows us a Neo-Tokyo that is both a miracle of reconstruction and a prison of inequality, ready to collapse again upon itself. Novels such as Matheson's I Am Legend and Boulle's Planet of the Apes had already explored loneliness and the collapse of civilization, but Akira's specific influence lies in the aesthetics of the cyberpunk metropolis as a permanent battlefield. It is the image of a technologically advanced but socially ruined society, a jungle of holographic skyscrapers and violent slums, which would become the model for countless subsequent works. The Fallout video game series, to give a contemporary example, shares with Akira a fascination with a retrofuturism marked by nuclear trauma. Above all, the Wachowski sisters have openly stated that without Akira (and Ghost in the Shell), The Matrix simply would not exist: from the sense of urban alienation to the figure of the chosen one with almost divine powers, to the aesthetics themselves, the debt is enormous and obvious.

The Zaibatsu (the large corporations that rule the world), the hacker world, and the hyper-technological future are cornerstones of cyberpunk, and Akira reinterprets them in its own way. Although the film does not focus on computer hacking, the theme of information control is central. The government and the army, represented as a monolithic, faceless entity reminiscent of state corporations (the Zaibatsu, in fact), hold the secret of the Akira project, a power they cannot control but desperately seek to hide. Resistance groups and religious sects that worship Akira seek to uncover or appropriate this forbidden knowledge. The hyper-technological future is not clean and sterile. It is a dirty, ‘used’ future, where powerful motorcycles speed past piles of rubbish and where the most advanced medical technology is used for inhumane experiments. The real fear does not come from artificial intelligence, but from biological intelligence, from the terrifying potential hidden in our own DNA, a Pandora's box that science, in the service of military power, has unfortunately opened.

It is essential to remember that the film is an incredible synthesis of the monumental manga of the same name, written and drawn by Ōtomo himself. The paper version, over two thousand pages long, is an even more vast and complex fresco, delving into the political dynamics, the mythology of psionic powers, and the fate of the characters after the second apocalypse that devastates Neo-Tokyo halfway through the story. The film's production was an almost insane gamble: it began and ended before the manga itself was finished, forcing Ōtomo to create a standalone and coherent cinematic ending. The film's global success then served as a catalyst for the manga's spread in the West, creating a perfect symbiosis and establishing the work as an all-encompassing cultural phenomenon.

The legacy of Akira is, quite simply, incalculable. For animation, it was the film that convinced Western audiences and critics that ‘cartoons’ could be a vehicle for complex, violent, philosophical and artistically stunning stories. It opened the floodgates for the anime invasion of the 1990s. For live-action cinema, its dynamic editing, sense of scale, and visual grammar have become part of the DNA of countless filmmakers. But perhaps its most powerful legacy is thematic. In an age of social unrest, distrust of institutions, anxiety about technological progress that seems to be spiraling out of control, and apocalyptic fears, the story of a group of rebellious teenagers facing the collapse of their civilization resonates with an almost frightening force and relevance. Akira is not just a film to see before you die; it is a work that, in a sense, has already shown us what the end of the world could be like, and it has done so with such incredible style that we can almost touch it.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...