American Beauty

1999

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

One of the most beloved films by audiences and critics, winner of five Oscars (Best Picture, Best Director, Best Cinematography, Best Original Screenplay, and Best Actor for Kevin Spacey), American Beauty was not just a triumph at the box office and in awards ceremonies; it was a bolt from the blue, a perfect seismograph of the fin-de-siècle anxieties that were simmering beneath the polished surface of late-millennium American prosperity. It is no coincidence that it emerged precisely at that historical juncture, offering an acute lens on the disintegration of bourgeois values and the search for authenticity in a world increasingly addicted to appearances.

Sam Mendes dives into the poetics of the everyday, and he does so through the gaze of a fifty-year-old man in an identity crisis who falls in love with his daughter's teenage friend. His cinematic debut is a visual and narrative ballet that elevates the banal to an existential metaphor, transforming domestic drama into a universal parable on solitude and the search for meaning. He does not merely observe, but dissects the family unit with surgical precision, revealing its hypocrisies and repressed aspirations. In this sense, the film fits within a rich tradition of works that explore the dark side of the suburban American dream, from David Lynch's Blue Velvet, albeit with less overtly surreal and more realistic tones, to novels like Richard Yates' Revolutionary Road, the film adaptation of which Mendes himself would later direct.

The result is a work of dual nature in which the blossom of uninhibited and worldly youth intersects with a pathetic maturity in its attempts to emerge from indolence. This duality manifests not only in the generational conflict but also within the characters' own psyches, torn between what they are and what society expects from them. The film is a symphony of contrasts: the artificial beauty of suburban gardens against the disheveled authenticity of a plastic bag dancing in the wind, sterile formal perfection against the emotional chaos bubbling beneath the surface, all accompanied by Thomas Newman's melancholic and iconic soundtrack, which weaves an emotional tapestry of subtle unease and fleeting hope.

Feelings, aspirations, sensations, and emotions are filtered through the directorial lens, which provides a perfect cross-section of middle-class American family life, oppressed by its small daily dramas and marital crisis. But Mendes's critique goes far beyond mere portraiture. It is a ruthless investigation into the futility of unbridled consumerism, the obsession with status, and the inability to communicate that afflicts a society where image has supplanted substance. The house itself, a symbol of success and stability, proves to be a gilded cage, a theatre of silent frustrations. The film exposes the kitsch of an existence in which even emotion is standardized, happiness a product to be purchased, and relationships a performance to be maintained.

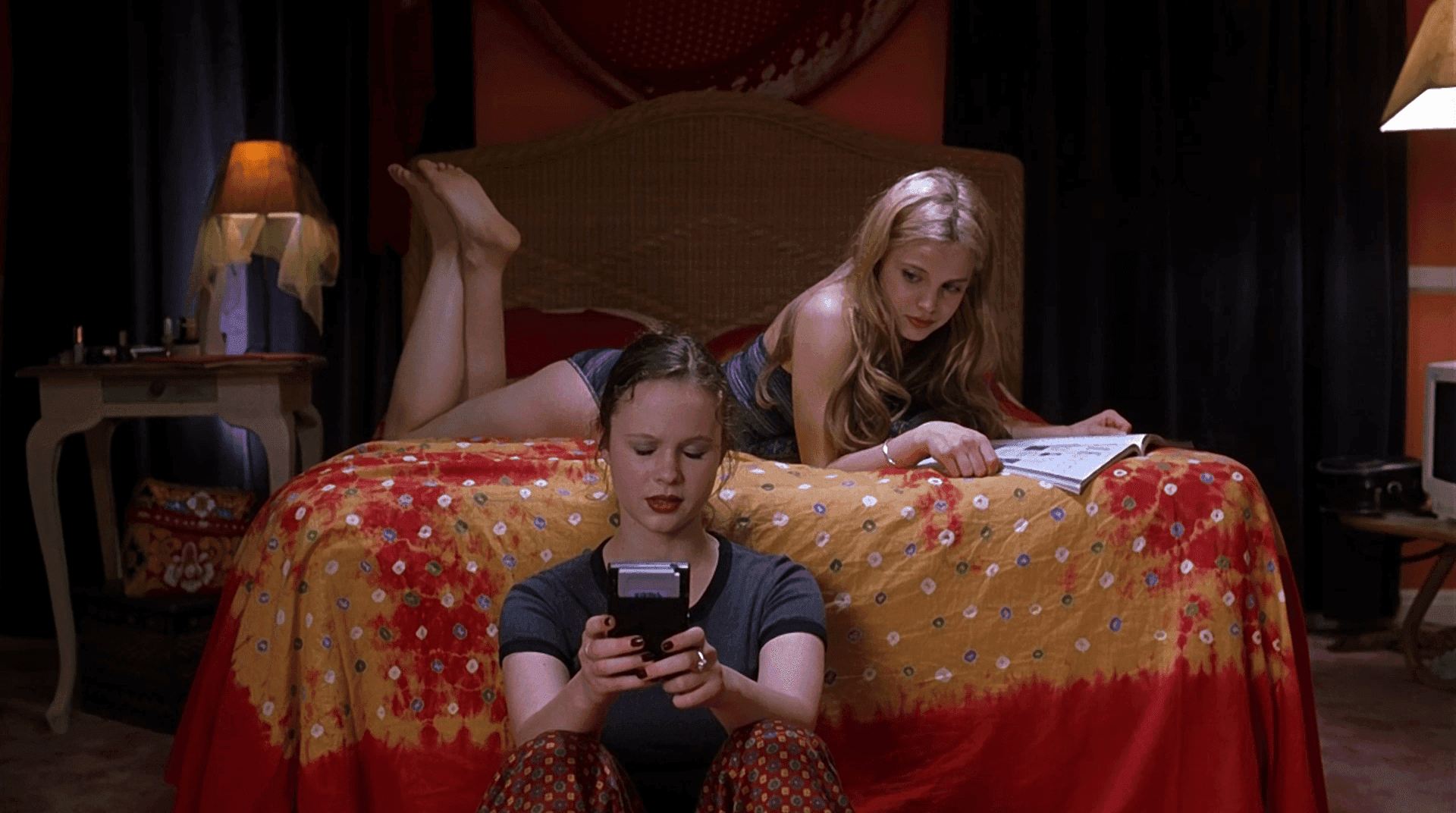

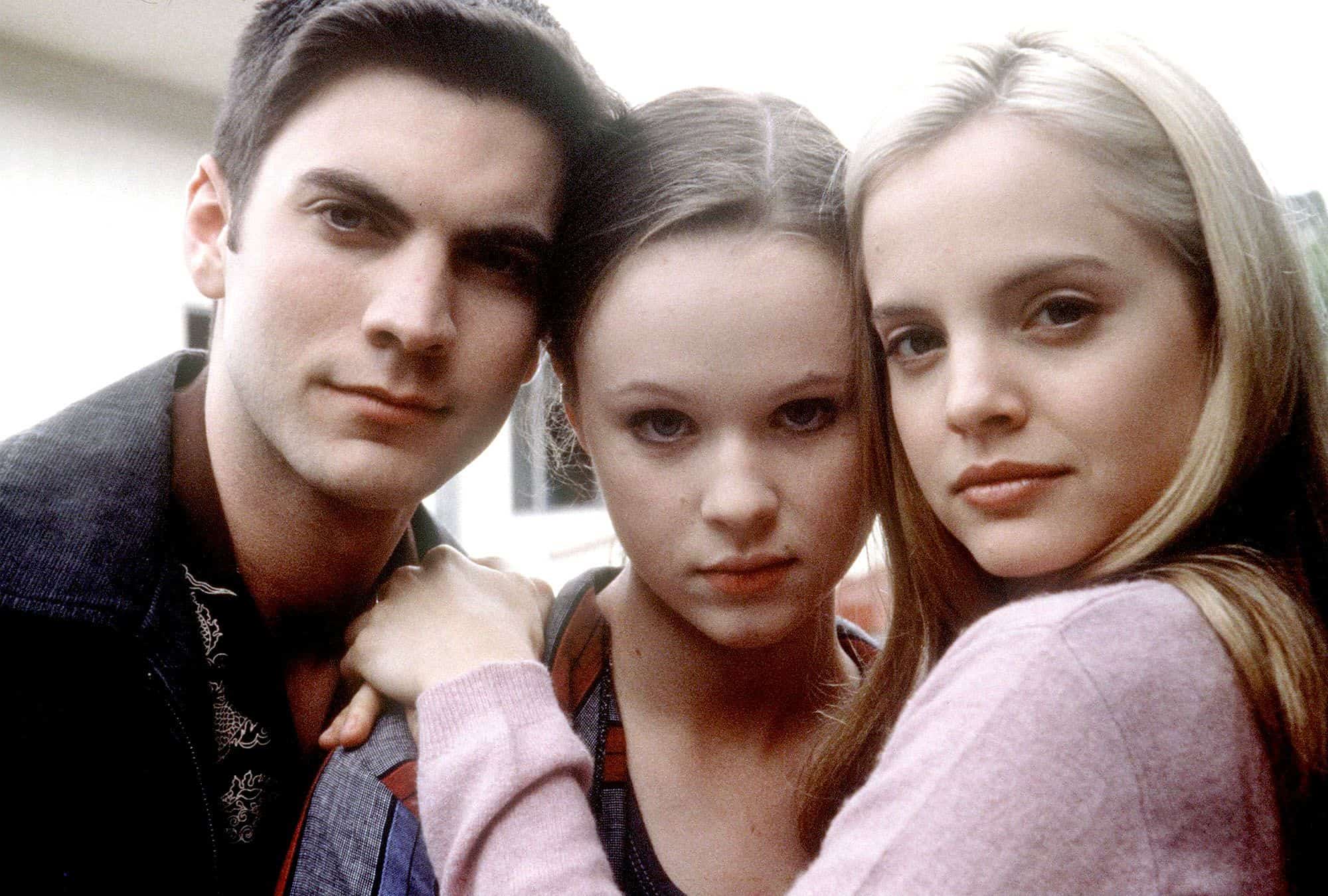

This is a dimension where identity crisis triggers the metamorphosis of its characters: Lester wants to free himself from social constraints to pursue a life on his own terms; Jane, the daughter, wants to be and not merely appear, wanting to love that strange boy next door without caring what her friends say; while Carolyn, frustrated by career setbacks, betrays her husband with one of the most successful real estate agents. This is the gallery of characters populating the universe of American Beauty: individuals desperately searching for meaning, each in their own way. Lester, in his reversal of the traditional role of family patriarch, embodies rebellion against emotional emasculation; Carolyn is the quintessence of the distorted American Dream, the career woman who sees her value measured only by external success, a tragic figure whose devotion to outward success leads her to betray every authentic desire; Jane, with her dark aesthetic and cynical gaze, represents a youth that rejects parental illusions; while Ricky Fitts, the voyeuristic and drug-dealing neighbor, proves to be the true aesthete, the only one capable of grasping sublime beauty in the ordinary and even in decay, an almost Brechtian observer who guides us through the madness of his community.

Lester Burnham is a forty-two-year-old man oppressed by a hysterical, social-climbing wife obsessed with her work as a real estate agent. He must endure her outbursts, betrayals, and obsessive, oppressive behavior. His "awakening" is less an escape from an unhappy marriage and more a desperate attempt to recover lost authenticity, a glimmer of vitality that suburban existence has robbed him of. His infatuation with Angela Hayes is not so much carnal desire as the projection of a freedom and purity he believes he has lost. It is a chimera, a catalyst for his transformation, a detonator for a long-awaited inner implosion.

At a performance by his daughter, a cheerleader for a local team, he meets Angela and falls madly in love with her. A love steeped in passion that leads Lester to quit his job and completely alter his lifestyle. His descent into "deviancy" in the eyes of society – abandoning his career, smoking weed, working in a fast food restaurant – is actually an ascent towards his true essence, a rejection of the conventions that were suffocating him.

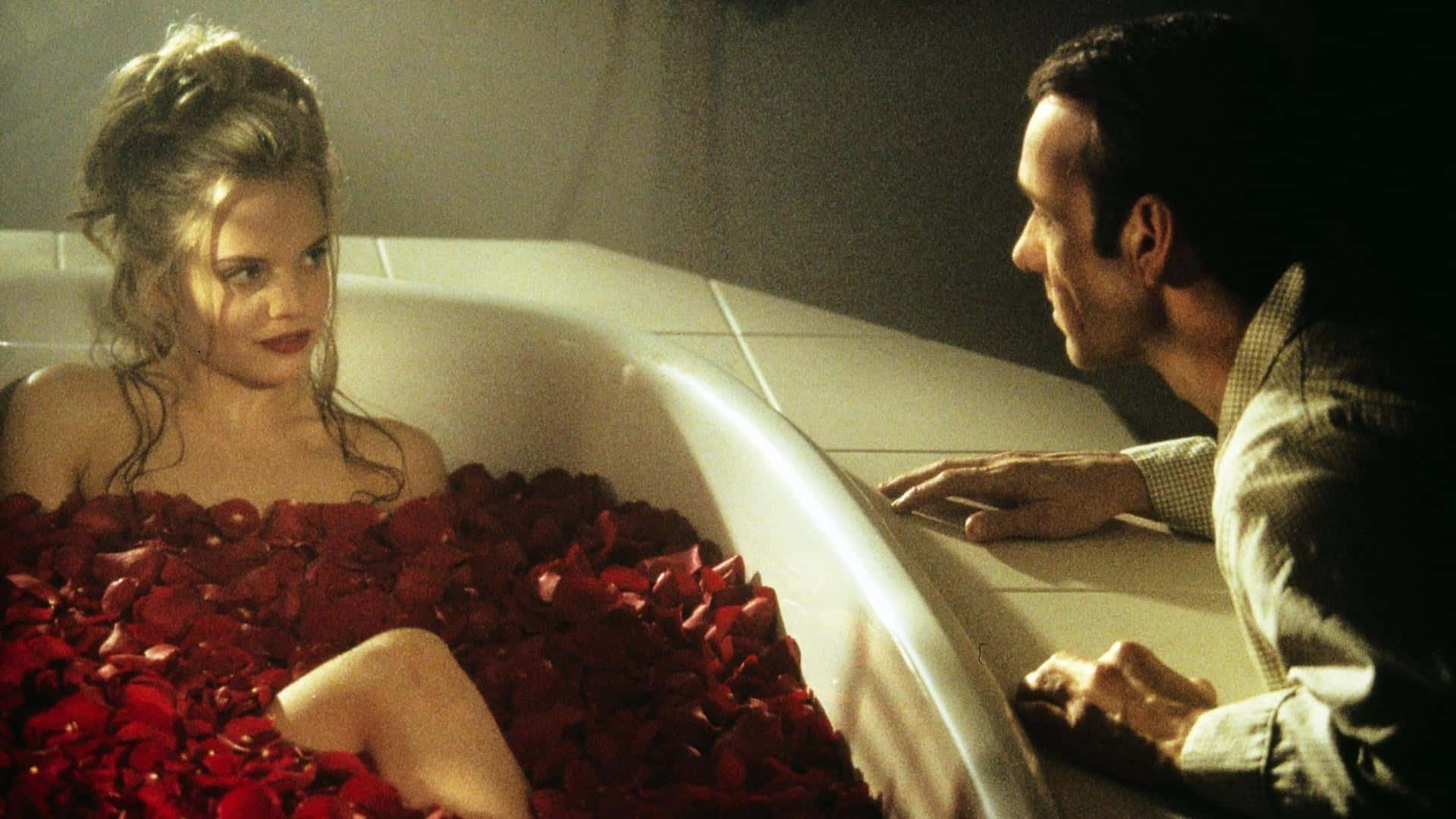

Many scenes make this film a wonderful iconographic gallery of memorable sequences, but the most renowned and celebrated is undoubtedly Lester's dream in which Angela appears enveloped by a sea of red rose petals while winking mischievously. This is not just an erotic fantasy; it is a true visual epiphany, a moment of sublime surrealism that Conrad L. Hall, the cinematographer, transforms into living art. The dominant use of red, the color of passion but also of danger and artificiality (like American rose bushes), here becomes a metaphor for the life Lester desires. The sequence of petals, floating and enveloping him, immediately became a cultural icon, a universal symbol of ephemeral beauty and obsession that blurs the boundaries between desire and reality, evoking the dreamlike opulence characteristic of the aesthetic of that era.

As testament to the interpenetration of the dream world and the pragmatic one, the petals emerge from the vision to gently fall upon Lester's beatified face. This is the genius of Alan Ball's screenplay, which manages to infuse magic into the everyday and suggest that beauty, like horror, resides in the eyes of the beholder. The film constantly moves on this fine line, prompting the viewer to reconsider what is truly beautiful or noteworthy. Ricky's famous monologue about the plastic bag dancing in the wind is the manifesto for this philosophy: an unexpected, unconventional beauty that manifests in the ordinary and the transient, a form of post-modern "found art" that contrasts with the artificial perfection of suburban life, inviting an almost Zen contemplation of reality.

Ultimately, it is a work that fiercely chastises the ideals of a social class without points of reference: Lester takes his life into his own hands to become a pathetic surrogate of himself, a pale shadow of Nabokov's Humbert Humbert, a cynical and disillusioned man overwhelmed by life. But his "pathetic nature" is a lens through which to observe the broader pathology of the surrounding society. While Humbert embodies predatory perversion, Lester is rather the victim of a system that has hollowed him out, and his "rebellion" is a last, desperate cry for authenticity. His end, tragic yet cathartic, seals the fate of a man who chose to break the invisible cages of conformity, even at the cost of his life. American Beauty is not just a biting satire; it is an elegy for the lost American soul, a warning about the fragility of happiness built on appearances, and an invitation to find beauty in imperfections, before it's too late. Its resonance endures because its questions about happiness, authenticity, and the meaning of life remain painfully relevant.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...