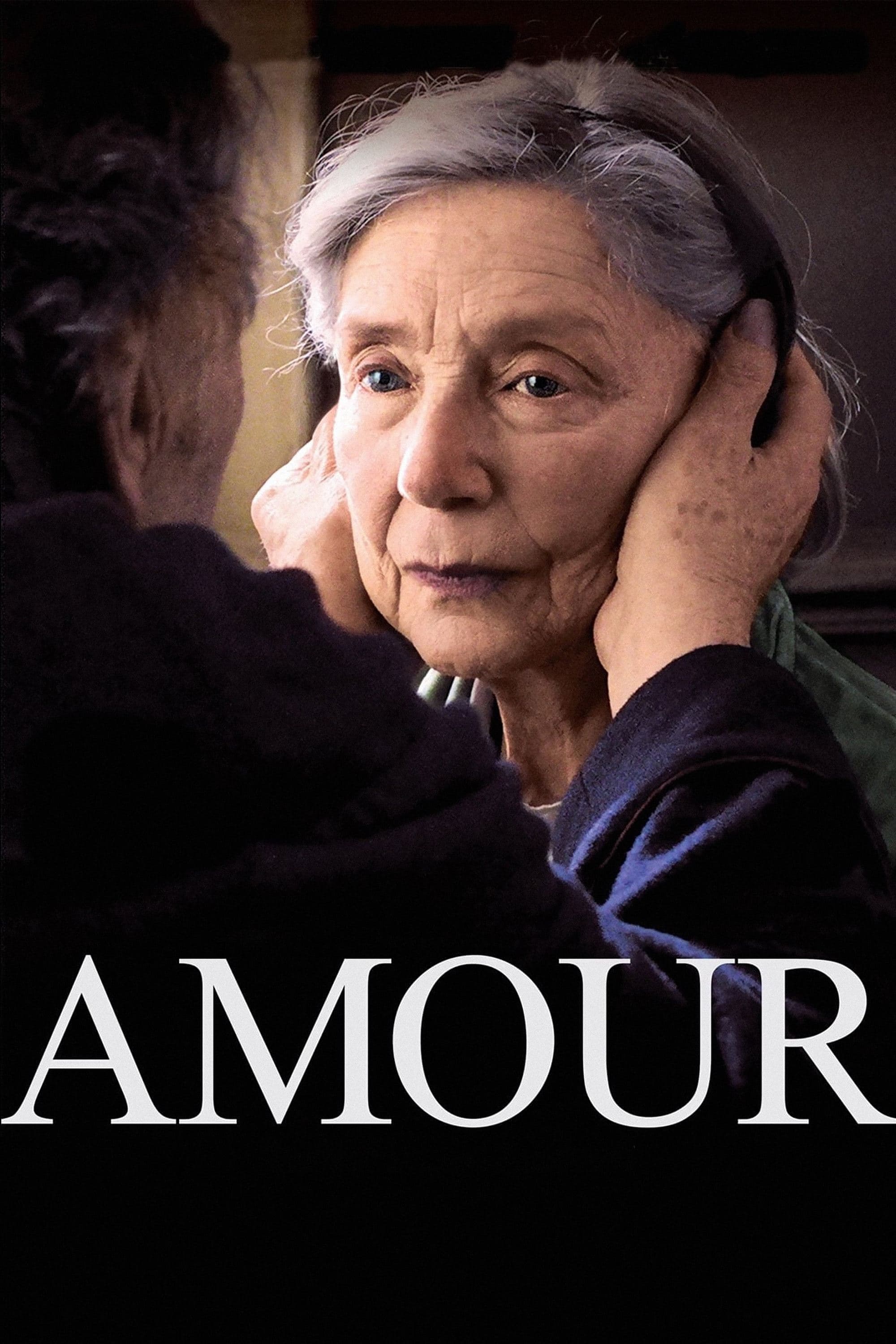

Amour

2012

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

A film of chilling beauty, this one by Haneke, a bitter account of the decay of body and spirit. Its beauty does not sugarcoat, but reveals the unspeakable with the precision of a scalpel, a kind of tragic sublime that arises not from the idealization of suffering, but from its rawest and most inexorable exposure. It is an aesthetic of uncomfortable truth, where every shot, every silence, is calibrated to maximize emotional impact without ever slipping into cheap sentimentality, an exercise in detachment that paradoxically generates a profound empathy.

Haneke is a master of creeping unease. If in The White Ribbon he inserted this type of feeling within a community, nurturing it to study its effects on a microcosm of people with the meticulous reconstruction of a latent social pathology in the heart of pre-war Germany, in Amour the unease, the non-belonging, the progressive drift from one's love and subsequently from reality, manifests within a couple, sanctioning its dissolution. Here, the malaise is not a social plague, but an intimate, visceral corrosion that lurks within the domestic walls, transforming a sanctuary of love into a prison of suffering. Haneke, with his unmistakable cold and analytical lens, shifts his gaze from the endemic illness of a society to the more universal and inevitable fragility of the human condition in the face of the inexorability of time and death. The absence of diegetic music for much of the film, the obsessive use of fixed shots that transform the viewer into a passive, almost complicit, voyeur, are elements that contribute to building this sensation of palpable unease, a suspended atmosphere nourished by the unsaid and by what is shown with brutal honesty.

The story is that of Georges and Anne, an elderly retired couple of music teachers who serenely live out the twilight of their lives in the company of memories and music. Two giants of French cinema, Jean-Louis Trintignant and Emmanuelle Riva, lend their artistic stature and personal history to these characters, imbuing them with an authentic dignity and fragility that transcends mere acting. Their mastery in the musical field, a universe of harmony and precision, stands in heartbreaking contrast to the chaos and dissonance that will erupt into their lives. Their days are woven from a delightful routine that makes them complicit, a symphony of daily gestures, knowing glances, small established habits that represent the solidity and beauty of a love built brick by brick over decades.

The imposing cathedral of their love is suddenly swept away by a stroke that strikes Anne, leaving her infirm and unable to be independent. The traumatic event is not just a narrative turning point, but a fracture that tears the fabric of their existence, a barbaric invasion that destroys the pre-existing harmony. The house, previously a refuge of intimate happiness and cultural exchange, gradually transforms into a claustrophobic theater of decay, where every space, every object, takes on the oppressive weight of disintegration.

Georges will have the painful task of caring for Anne with the help of a nurse, witnessing the love of a lifetime stolen by cruel fate. A task that is not only physical, but above all moral and existential. His face, etched by suffering and vigilance, becomes the mirror of a soul consumed in the desperate attempt to preserve a shred of dignity for his beloved, and for himself. Their daughter, Eva (portrayed by an intense Isabelle Huppert), though present and concerned, remains somewhat external to the abyss that opens up between her parents, unable to fully grasp the nature of the bond that ties them and the nuances of a final decision Georges is forced to confront alone.

It will be an opportunity for him to forge a pact with solitude, agonizing over the memories of an existence spent beside a woman he now sees petrified and annihilated on a bed. This solitude is not due to physical absence, but to the progressive loss of connection, to watching the person he has loved for an entire lifetime slip away, reduced to a shell, a painful memory of herself. Haneke spares us nothing of this emptying process; his penetrating gaze fixates on the most uncomfortable details: difficulty eating, incontinence, loss of autonomy, increasing aphasia. He is not interested in dramatizing these aspects, but in showing them with the precision of a documentarian, leaving the viewer to bear the weight of reflection and silent horror.

Haneke shatters every convention and plunges his gaze into the twilight of a man, onto the nihilistic moral and physical devastation that strikes him at the end of a life that proves ferocious and brutal in its mechanistic cyclicality. The choice to film almost entirely within a bourgeois apartment contributes to emphasizing Georges' emotional claustrophobia and imprisonment, trapped in his devotion and pain. The Austrian director categorically refuses to offer escape routes or easy consolations, avoiding any melodramatic drift typical of other cinematic representations of old age and illness. His is a cinematic philosophy that imposes an active, almost painful, participation on the viewer in the drama unfolding on screen, forcing them to confront their deepest fears about loss and death. It is not nihilism understood as a belief in nothingness, but rather as a bitter acknowledgment of the precariousness of meaning in the face of inevitable physical and mental dissolution.

The heartbreaking lyricism rising from Georges' silent pain is the knife that silently tears at the flesh of each of us, it is the unexploded obsession of an immense loss for which no one can provide a remedy. This lyricism is not expressed through soft words or music, but through the power of the unsaid, of fixed shots that linger on faces furrowed by time and sorrow, on silences dense with meaning. It is the lyricism of an agony lived with dignity, of an extreme sacrifice that challenges common morality in the name of absolute love, but which at the same time questions the very nature of compassion and euthanasia, without providing ready-made answers. Amour is not just a film about old age or illness; it is a profound meditation on the essence of love, on human dignity, and on ultimate solitude in the face of the mystery of the end. A work that, with its ruthless honesty, imprints itself on the viewer's memory, leaving an indelible mark as only masterpieces can.

Main Actors

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...