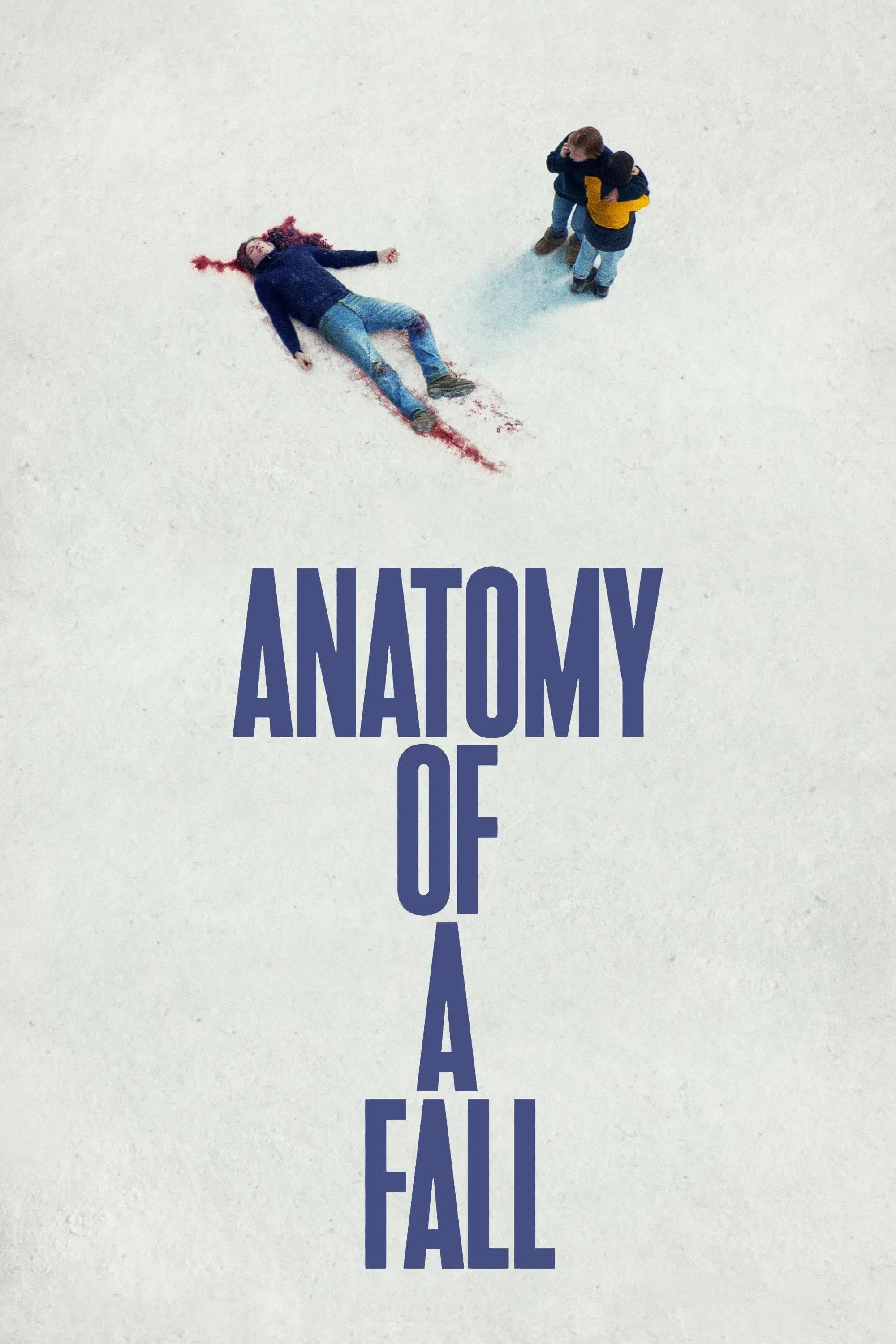

Anatomy of a Fall

2023

Rate this movie

Average: 4.50 / 5

(4 votes)

Director

When the art of cinema ventures into uncharted territory, such as ethics, it sometimes gives rise to precious gems to be jealously guarded. Such is the case with Justine Triet's Anatomy of a Fall, the well-deserved winner of the Palme d'Or at Cannes. It is a work that rejects the consolation of certainty in favor of the unease of doubt, a psychological thriller disguised as a courtroom drama, or perhaps the reverse. A work of dazzling formal purity, it delves into the moral dilemma of a partially blind boy, Daniel, whose mother, Sandra, is suspected of killing her husband, Samuel, after pushing him (or perhaps not?) from a balcony, and who is the only, problematic witness to the event.

Justine Triet's film fits powerfully into that noble tradition that sees cinema and literature not as tools for providing answers, but for formulating more complex questions. We are in Pirandello territory, in a judicial Così è (se vi pare) where objective truth is an unattainable hypothesis, a ghost hovering over the courtroom but which no one can grasp. Triet's work shares its philosophical DNA with Akira Kurosawa's masterpiece Rashomon, but with one substantial difference: there we had multiple versions of the same event; here, we have no reliable version of the crucial event—the fall. The ethical dilemma is not so much “which version is true?” as “which version do we choose to construct and believe?” The inner conflict of the characters, particularly that of young Daniel, is not a struggle between truth and falsehood, but a painful selection of the narrative that will allow him to survive, to continue living with one of his parents, knowing that his narrative choice will condemn or absolve the other.

The relationship between Sandra and her son Daniel is the beating, bleeding heart of the film. The trial is not just an external event they undergo, but a chemical reagent that transforms the very nature of their bond. The courtroom becomes a public stage where family intimacy is dissected, analyzed, and used as a weapon. Daniel, once a protected child, is violently promoted to the role of key witness and, ultimately, moral judge. He is a little Oedipus forced to probe the nature of his parents' relationship, to confront their faults, their frustrations, and their unhappiness. The ethics of this filial conflict are heartbreaking: to save his mother, Daniel must take a leap of faith, a choice based on a “truth” that he himself constructs, piecing together a memory that may be real, may be induced, or may simply be necessary. It is a terrible reversal of the parental role, where the son finds himself having to ‘create’ a sustainable reality in order to continue having a mother, making an adult choice whose shadow will haunt him forever.

The genius of the film lies in its refusal to solve the mystery. Samuel's death could be suicide, the result of depression and artistic failure; an absurd accident; a murder stemming from a furious argument. All three options are tragically plausible and, in their own way, banal. Triet denies us the satisfaction of a solution, the catharsis of a revealing flashback. Instead, he forces us to share the jury's and Daniel's disorientation. We are inundated with fragments: expert reports, bloodstain analysis, conflicting theories and, above all, the audio recording of a devastating argument. We hear the escalation of verbal violence, but the screen remains black, leaving it to our imagination to visualize the horror. This narrative device makes us active participants in the process, not mere spectators. It forces us to judge, to doubt, to take a stand, and then shows us the fragility of our certainties.

Anatomy of a Fall uses the framework of the classic mystery with exquisite intelligence and then empties it from within. We have all the elements of the genre: a body, a potential murder weapon, a suspect with ambiguous behavior, a tenacious lawyer, a ruthless prosecutor, and a mystery to solve. However, Triet takes this perfect mechanism and uses it not to arrive at the truth, but to demonstrate its impossibility. It is an anti-whodunnit, where the question “who did it?” becomes progressively less important than “who were these people?” and “what remains of a love when it is put on trial?” The film dismantles the comfort of the detective genre, suggesting that real life, unlike an Agatha Christie novel, is often a puzzle with the most important pieces missing, and that justice is not the discovery of the truth, but the affirmation of the most convincing narrative.

The courtroom is an arena where the battle is fought not with weapons, but with words. The dialogue is fiercely confrontational: every aspect of Sandra's life (played superbly by Sandra Hüller) is taken out of context and used against her. Her successful career becomes proof of her manipulative nature; her novels, which draw on her life, are presented as premeditated evidence; her bisexuality is used to paint her as an unreliable adulteress. Her apparent coldness, her “icy” nature, is not a sign of guilt, but the armor of a woman and an artist who sees her entire existence, her language, her identity, being dismantled and reassembled into a monstrous caricature by the prosecution. Her performance is a masterpiece of control and implosion. Beneath the intellectual and controlled surface, we sense a volcanic inner drama that erupts only in the intimacy of a confrontation or in the violence of an audio memory. The film shows us a woman who is fighting not only for her freedom, but for the right to her own complex and unjudgeable truth.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...