A Clockwork Orange

1971

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

A Clockwork Orange is a kind of culmination point in Stanley Kubrick's artistic journey. From the strategic rigor of Paths of Glory to the almost spiritual and transcendental exploration of 2001: A Space Odyssey, Kubrick had consistently probed the limits of the human condition and the relationship between the individual and the system. With A Clockwork Orange, he undertakes a far more visceral and uncomfortable immersion, abandoning stellar horizons for a dystopian exploration of the darkest impulses rooted in the human soul and, above all, society's reaction to such aberrations. It is not just a culmination point, but almost a definitive essay on the dichotomy between free will and conditioning, a theme that would continue to resonate through his cinema, albeit with different tones.

It represents his effort to approach youth behavioural extremism and the consequent social unrest linked to phenomena of violence and rejection of civil norms. The film does not merely portray youth deviance, but analyzes its root in a dysfunctional and hyper-technologized society, where morality seems to be an option and the individual finds himself lost between brute violence and authoritarian control. The futuristic and desolate London, with its brutalist architecture and kitsch, alienating interiors, becomes a metaphor for a West that, in the 1970s, was beginning to confront its own contradictions, caught between the explosion of countercultures and the growing demand for order and security, often at the expense of individual liberties.

The film is based on Burgess's novel of the same name, in which violence is the protagonist of the story in every facet: from physical to the more insidious, which originates in the psyche and extends, finally overriding, the thoughts of other human beings. Kubrick's transposition of Anthony Burgess's text is not a mere reproduction, but a sharp and ruthless reinterpretation of the philosophical implications underlying the concept of "clockwork orange": a biologically living entity (an orange, symbol of organic nature) yet mechanically conditioned (a clock, symbol of unnaturalness and coercion). Violence, far from being merely a physical act, manifests as a perversion of desire, as an instrument of social control, and ultimately, as a denial of individual dignity. Kubrick's choice to omit the novel's final chapter, in which Alex seems to mature independently, strengthens his nihilistic and disenchanted vision: man, according to the director, is destined for a perpetual cycle of violence and submission, without intrinsic redemption.

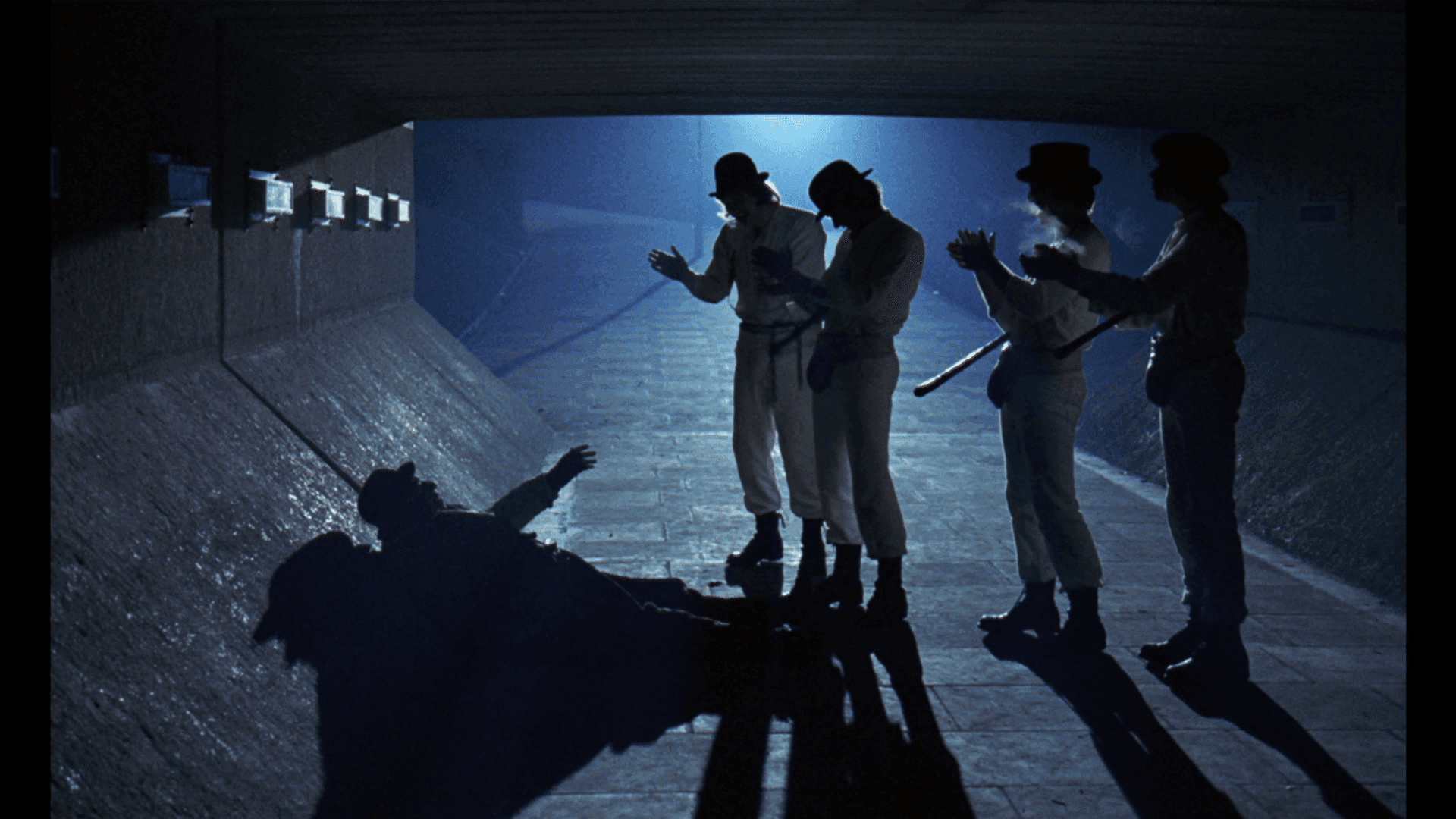

Alex roams with his companions, the self-proclaimed Droogs, in a spectral city, indulging in atrocities of every kind: he beats a homeless man under a bridge, fights a rival gang in an abandoned theater, breaks into a writer's home and rapes his wife to the tune of "Singin' In The Rain" (a scene conceived on improvisation by Malcolm McDowell himself). Malcolm McDowell's glacial charisma as Alex DeLarge is the beating heart of this portrayal of evil. His performance, as calibrated as it is disturbing, embodies lost and corrupted youth, the perverse genius that finds expression in classical music as much as in the most heinous brutality. The rape scene set to "Singin' In The Rain", as is well known, was a brilliant improvisation by McDowell on set, but its resonance extends far beyond the anecdote: it crystallizes the film's ability to subvert the collective imagination, transforming an icon of innocent joy into a soundtrack for horror, a mechanism that elevates violence to a true artistic performance, provoking a deep and lasting discomfort in the viewer. The aesthetic of the Droogs – their white uniforms, bowler hats, Alex's made-up eye – has become an archetype of nihilistic rebellion, a powerful iconography that has influenced generations of artists and designers, and which still resonates today as a warning of social unrest never fully quelled.

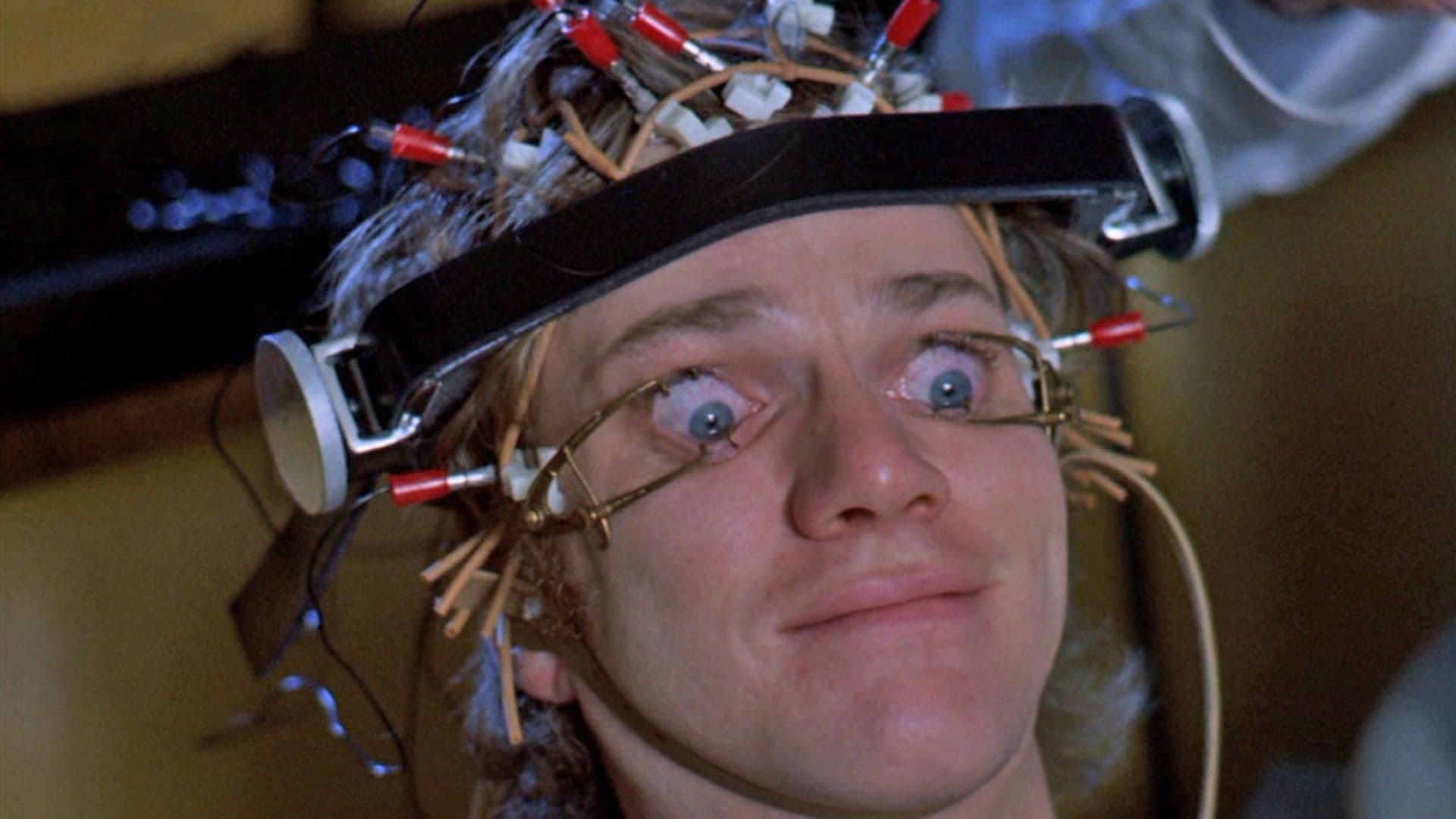

But fate has something special in store for him: the same ferocity he unleashed upon the world will be, Dantesquely, turned back on him. The "Ludovico Technique" is not a simple punishment, but the focal point of the film's ethical debate. It is an experiment in social engineering that aims to eradicate evil not through understanding or re-education, but through the most brutal Pavlovian conditioning. The lysergic-like montage of the footage, accompanied by physical and pharmaceutical constraints, transforms Alex from perpetrator to victim of an equally tyrannical system. His free will is annihilated, his ability to choose between good and evil – if he ever possessed it – is eradicated, leaving an empty shell, a clockwork orange incapable of violence, but also of any authentic human reaction. The film asks us: is it preferable to have an evil man who freely chooses evil, or a 'good' man who can choose nothing but goodness, because he is conditioned to such an extent that he has lost his own humanity?

Indeed, once captured by the police, he enters a special rehabilitation program for the most violent cases, undergoing forced viewing of gruesome films presented with a lysergic-like montage. Once out of prison, he suffers the revenge of the society he had trampled upon. Society's "revenge" is imbued with a bitter and disorienting irony. Alex, the unpunished aggressor, becomes everyone's target: his former "Droogs", now policemen, beat him; the homeless man he himself assaulted attacks him; the writer, whose home was desecrated, tortures him. Every interaction is a cruel contrappasso, a demonstration that evil, once unleashed, generates an uninterrupted cycle of violence and reprisal. The ending, far from offering catharsis or redemption, leaves the viewer with a sense of profound unease. Alex's rehabilitation is merely a political farce, an apparent success that masks society's own ethical failure. The final image, with Alex imagining an orgy amidst the cheering crowd, suggests that his intrinsic nature has not changed, but has simply been repressed, ready to re-emerge as soon as the conditioning loosens, or perhaps, simply, that society is ready to accept the 'monster' if it serves its political aims. It is a circle that closes, without hope.

Innumerable memorable scenes: the rape set to "Singin' In The Rain", the orgy to the notes of Ludovico Van Beethoven, the evenings at the Moloko slurping "Milk-Plus". Beyond those already mentioned, the film's entire visual and sonic structure is a tour de force. The masterful use of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, transformed from a hymn to universal brotherhood into a soundtrack for Alex's most perverse visions, is a striking example of Kubrick's genius in perverting the familiar to create the terrifying. The sequences of the orgy or the 'cure' sessions are not only iconic for their visual audacity, but for the way classical music merges with brutality and dystopia, elevating discomfort to an almost subliminal level. And then the Moloko Bar: a riot of futuristic-kitsch art and design, with phallic sculptures and surreal furnishings, a temple of alienation where "Milk-Plus," a drugged mixture, serves to prepare the Droogs for their 'evenings'. Everything contributes to creating a cohesive and unsettling universe, a complex and stratified work of art that, fifty years after its release, continues to provoke, to make one reflect on the violence inherent in man and on the even more subtle violence of a system that attempts to control it, ultimately nullifying the very essence of the individual. An indispensable, uncomfortable, and prophetic masterpiece that continues to reverberate in the collective consciousness.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...