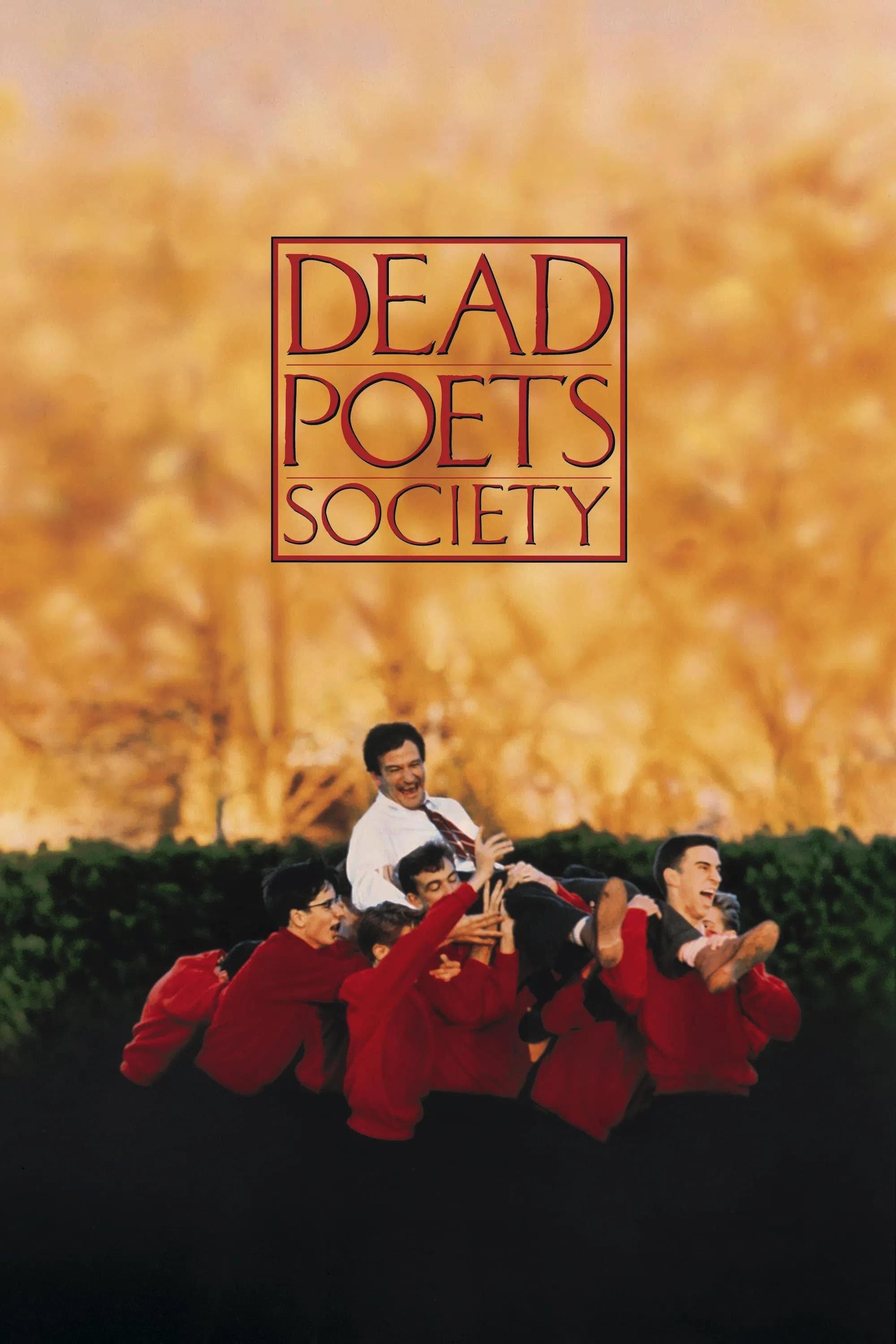

Dead Poets Society

1989

Rate this movie

Average: 4.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

Friendship as a fundamental value, student brotherhood, and complicity that acts as a shield against a hostile and incomprehensible adult world. These are the pillars on which Peter Weir's Dead Poets Society (1989) rests, a work that retains an almost miraculous emotional power and cultural relevance. It is not simply a “school movie,” but a passionate and poignant ode to intellectual rebellion, an elegy to adolescence as a territory of discovery and inevitable, painful conflict. The “Dead Poets Society” is not just a club, but a romantic conspiracy, a secret society that meets in a cave, a damp pagan sanctuary that contrasts with the solemn and rigid chapel of the academy. There, by torchlight, the boys do not just read poetry, but perform a rite of passage, forging a bond that is stronger than that imposed by their families or the school hierarchy.

Culture, in the gray and conformist world of Welton Academy in 1959, becomes a means of abstraction and elevation. The arrival of Professor John Keating is the arrival of a missionary, a prophet who does not proclaim a new gospel but rediscovers an ancient and deeply American one: that of Transcendentalism. Keating is nothing less than a direct heir to Henry David Thoreau, echoing his desire to “suck the marrow out of life”; to Ralph Waldo Emerson, with his calls for self-determination; and above all to Walt Whitman, the film's guiding spirit, whose libertarian spirit pervades every lesson. Keating asks his students to tear out the pages of a literary criticism textbook, not as an act of vandalism, but as an act of philosophical liberation: to reject schematic and sterile analysis in favor of the direct, emotional experience of poetry. “Carpe Diem,” the Horatian motto that drives the story, becomes the battle cry against the tyranny of the future planned by their fathers.

This youthful fervor is embodied by a group of extraordinary actors, but it is catalyzed by Robin Williams' splendid performance, which infuses the story with enormous pathos. His performance is a masterpiece of balance, a perfect alchemy that blends his irrepressible comic energy—his imitations of Marlon Brando and John Wayne—with a deep and gentle seriousness and melancholy. His John Keating is not just a ham, but a wounded soul, a former student of that same school who found his only true salvation in poetry and now seeks, with almost desperate urgency, to pass on the torch. It is the performance that defined his career, showing the world that behind the comic genius lay a dramatic actor of rare sensitivity.

The family problems of the young people become a mirror of a malaise from which it is difficult to escape. The conflict between Neil Perry (Robert Sean Leonard) and his father is the tragic heart of the film, the representation of an irreconcilable clash. Neil's father is not a monster, and that is his tragedy. He is a man who, in his rigid and pragmatic worldview, sincerely believes he is acting in his son's best interests, but his love is expressed as control, his protection as a cage. His inability to see and understand his son's passion for theater is symbolic of an entire generation of fathers, shaped by war and economic crisis, who see art as a futile luxury and youthful rebellion as unforgivable ingratitude.

This generational gap between adults and teenagers is masterfully resolved by Peter Weir's direction, which contextualizes the metaphor within the plot. Welton Academy, with its four pillars—‘Tradition, Honor, Discipline, Excellence’—is not just a backdrop, but an antagonistic character. Its Gothic architecture, its austere corridors, its strict rules are the physical manifestation of an authoritarian system designed to produce clones, not individuals. Weir thus places his film in a noble historical tradition, that of cinema and college, but elevates it. Compared to other works, Dead Poets Society does not have the anarchic goliardia of Animal House or the direct social criticism of Jean Vigo's Zéro de conduite. It is something different: a romantic and intellectual drama that firmly believes in the transformative power of ideas.

Finally, it is the poets quoted in the film who energize the story, with the beauty of their verses shining through the narrative. These are not mere quotations, but catalysts for action. It is Herrick's poem (“Pluck the rose when it is in bloom”) that prompts Knox Overstreet to court the girl he loves; it is Neil's passion for Shakespeare that gives him the courage to take to the stage; it is Whitman's barbaric verse that inspires Todd Anderson's first true act of spontaneous creation. Poetry ceases to be a dead text on the page and becomes a manual for living, a weapon to fight despair, and a language to express the inexpressible. The ending, with its iconic, unforgettable sequence—“O Captain! My Captain!”—is the perfect synthesis of Keating's legacy. It is an apparent defeat: the system wins, the professor is fired. But the gesture of the students standing on their desks is a moral and spiritual victory. It is proof that the idea has taken root, that they have learned not what to think, but how to think. They have found the courage to look at the world from another perspective, and this is a lesson that no disciplinary committee can ever erase. And for this, they pay a final poignant tribute to their departing Captain.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...