Back to the Future

1985

Rate this movie

Average: 4.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

This Robert Zemeckis film caught us all off guard in 1985, as we tried to grapple with the temporal paradoxes it unspooled and reckoned with past years and leaps into the past; we were ready to see a dramatic and serious science fiction film, but instead, we were met with a brilliant comedy, almost irresistible in its tone. It was a true cinematic coup de théâtre, a gut punch to genre conventions, but a warm embrace for an audience hungry for wit and entertainment. In a decade dominated by often redundant or overly serious blockbusters, Back to the Future burst forth with the freshness of a luminous idea, infused with a playful nostalgia for the 1950s and sharp irony regarding 1980s customs, serving as a shrewd cultural commentary beneath the gleaming veneer of a teen adventure.

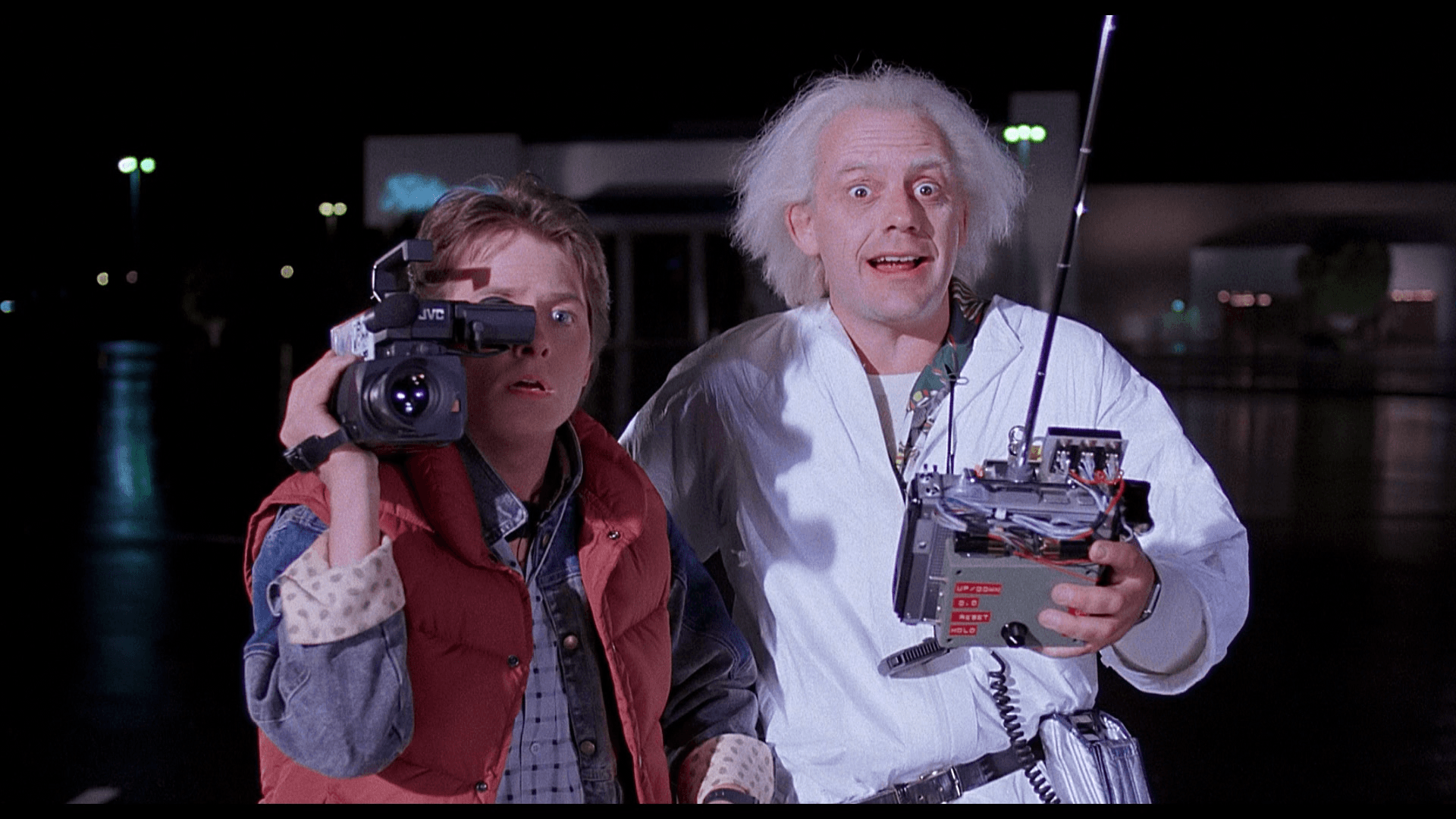

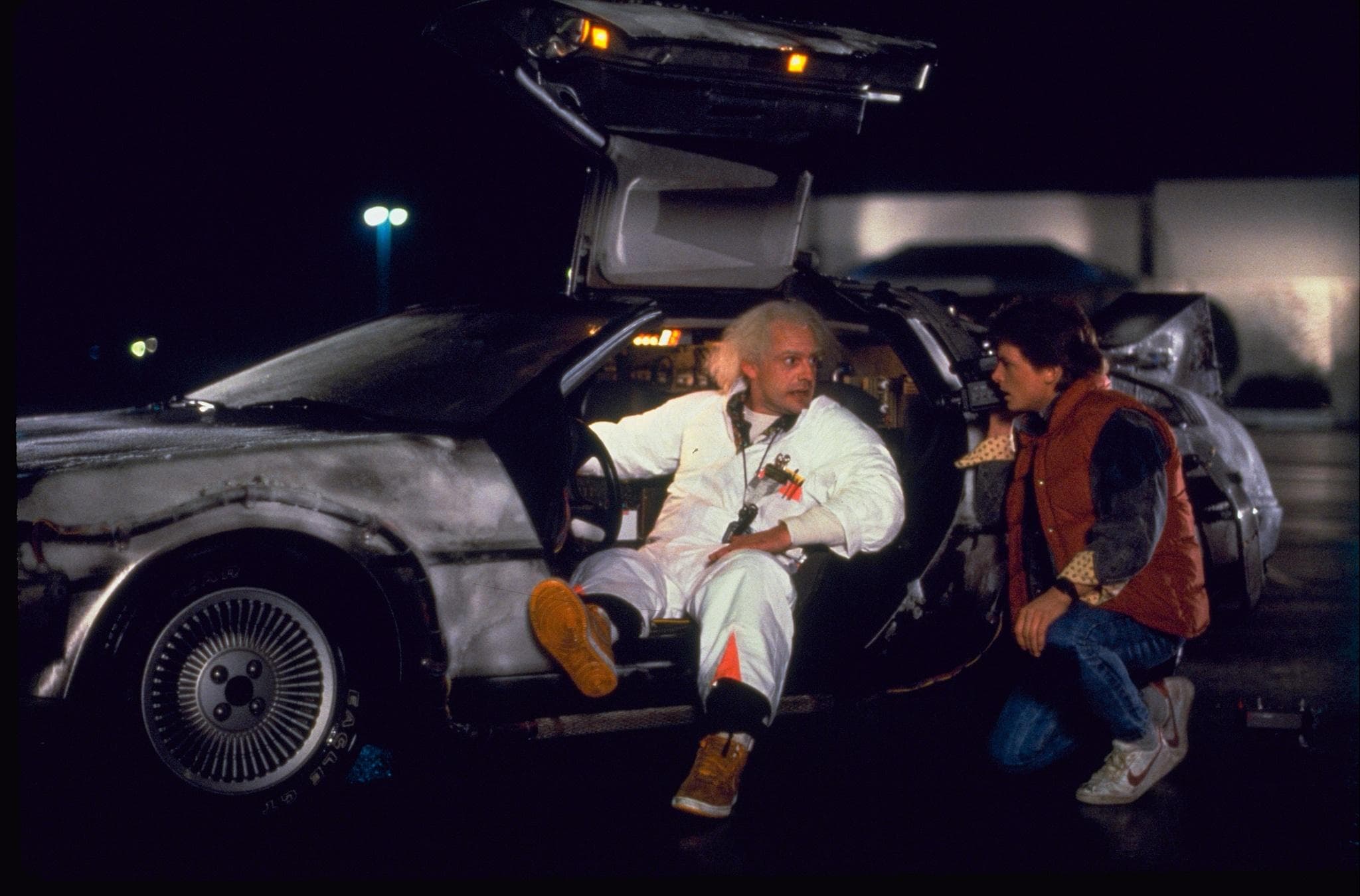

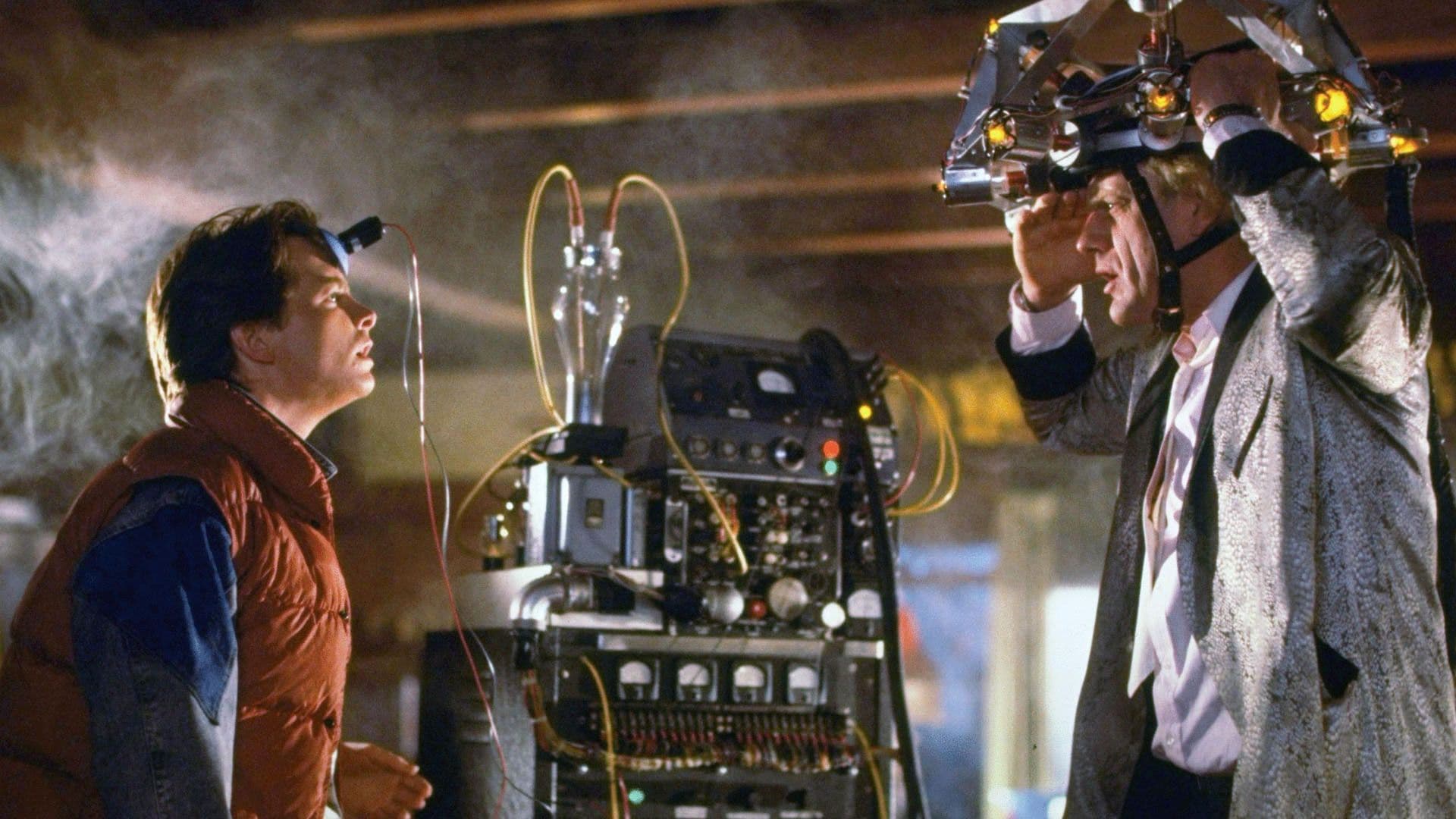

Marty McFly travels back in time to the sixties with his scientist friend’s invention, who installed a time machine on none other than a legendary DeLorean DMC 12, to escape a gang of terrorists from whom the scientist had stolen the radioactive material powering the machine. The DeLorean, a vehicle that had been a commercial failure in reality, in the film ascends to universal pop icon status, inextricably fused with the very idea of time travel—a conceptual paradox that only cinema can forge with such effectiveness. It's a design that screams "future" even when immersed in the past, with its gull-wing doors and stainless steel bodywork that seem made to reflect the sparks of the time jump. Doctor Emmett "Doc" Brown, portrayed by an unparalleled Christopher Lloyd, is the perfect counterpoint to Marty: an eccentric genius bordering on madness, whose cluttered laboratory is a sanctuary for ingenuity and absurdity, a modern Archimedes who traded levers for a flux capacitor. And the Libyan terrorists? An almost anachronistic note, a narrative MacGuffin that anchored the film to the geopolitical fears of the mid-1980s, but today sounds like a bizarre and almost innocuous echo of a bygone era.

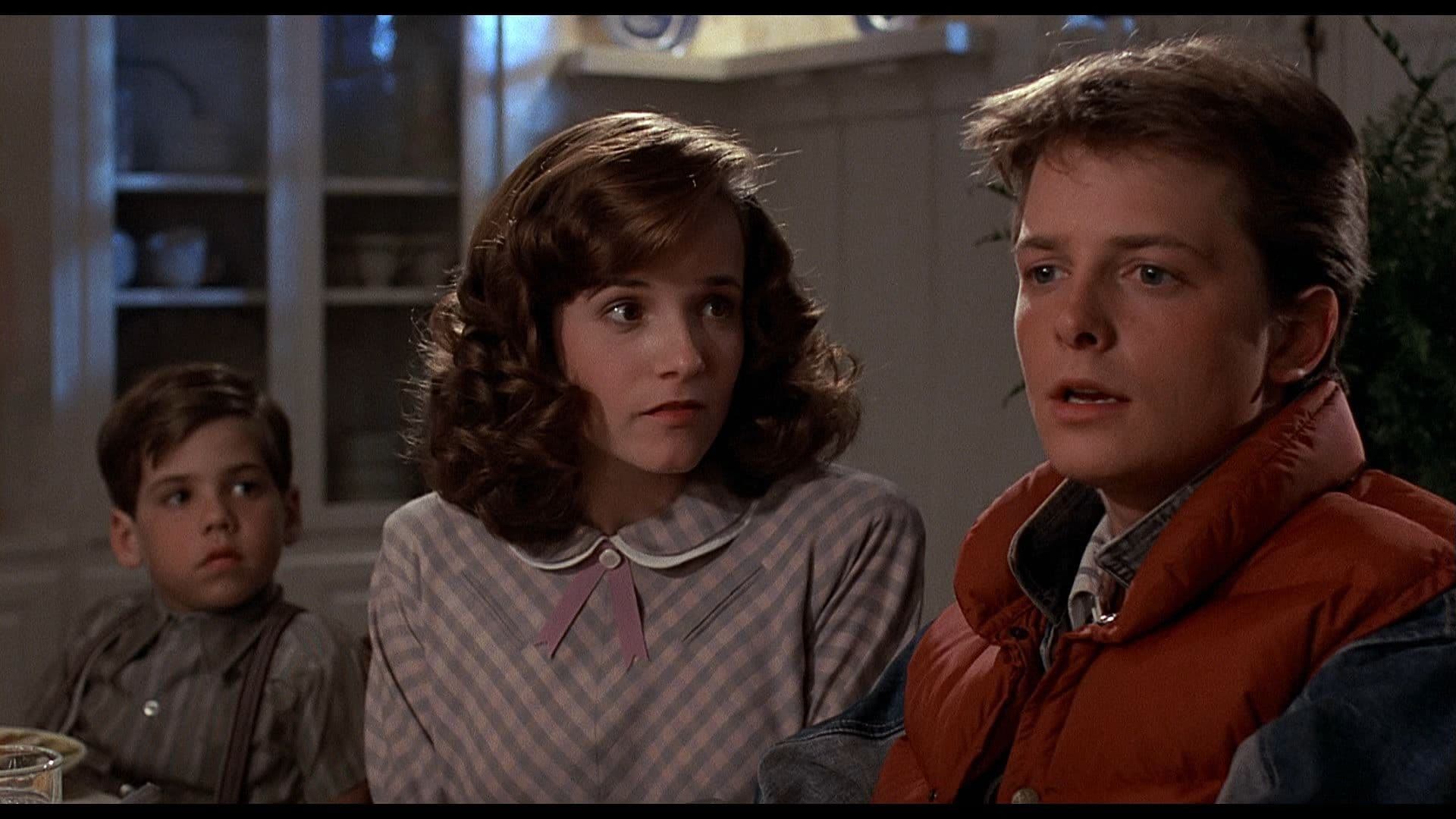

He will rediscover his father and mother as he had never known them, teenagers like him with their own burden of adolescent problems. The disillusionment upon realizing that his parents were not mythological and crystallized figures, but insecure, shy, awkward, or exuberant teenagers just like him, is a universal theme. Zemeckis and Gale do not merely play with temporal paradox, but probe the psychological depths of a reversed family bond: Marty, almost against his will, assumes the role of Cupid and mentor to his future parents. It is not just his future that hangs in the balance, but the entire genesis of his identity, an Oedipal labyrinth steeped in humor and tension that challenges simplistic portrayals of the parent-child relationship. The generational conflict is explored with unexpected subtlety, revealing the roots of those insecurities and aspirations that, once understood, make the bond even deeper and more authentic.

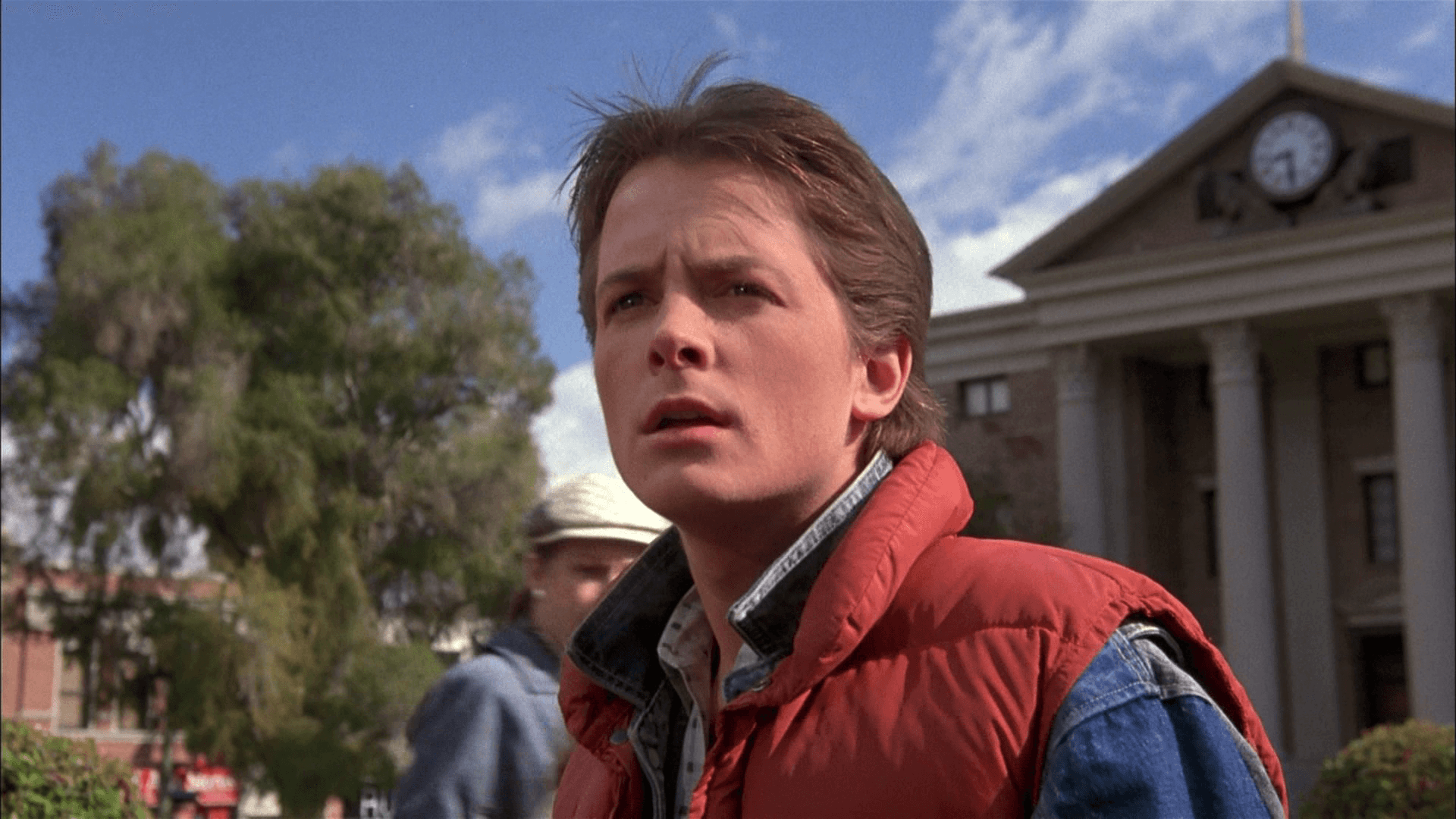

He must also repair the damage caused by his appearance and re-establish the correct course of events to secure his future. The film, with surprising effortlessness, navigates the intricate meshes of the "grandfather paradox," making it digestible and compelling even for viewers less accustomed to the intricacies of quantum physics. Every slight variation, from the famous fading family photo – an image of suspense as simple as it is effective – to the most trivial exchange of words, has the potential to rewrite not only Marty's personal history, but an entire timeline. It is a race against time that is, in itself, a shrewd meditation on the inevitability of destiny and the power of small individual choices. The constant anxiety that Michael J. Fox's Marty conveys, with his youthful frenzy and perpetually bewildered gaze, becomes our own anxiety for the preservation of a delicate temporal balance. The casting of Fox, who replaced Eric Stoltz after several weeks of filming, proved to be one of the most astute decisions in cinematic history: his energy, comedic timing, and innate empathy are the pulsating heart of the film, elevating the character beyond a mere caricature.

And meanwhile, he must harness the energy of a lightning bolt to store the power needed to make the quantum leap through time. A narrative engineering solution as fanciful as it is striking, that elevates the time travel device from a mere scientific contrivance to a truly epic, almost divine, event. The lightning bolt is not just energy, but a symbol of providential intervention, a flash of genius that shakes the universe and allows the impossible. It is the masterstroke that transforms science fiction into a high-voltage fairy tale, where scientific credibility is subordinate to visual impact and relentless pacing. The entire climax at the clock tower is a ballet of ingenuity and timing, an apotheosis of comedic-adventure suspense that few films have managed to equal.

The narrative's lightness serves as a counterpoint to a series of scientific postulates tough enough to introduce into a comedy, yet the film works perfectly. The secret to this balance lies in the screenplay by Bob Gale and Robert Zemeckis, a true lesson in narrative economy and character building, refined for years under the watchful eye of Steven Spielberg, who served as executive producer. Every line, every gag, every scenic element finds its resonance later in the plot, creating a dense yet never heavy visual experience. Alan Silvestri's score, with its energetic melodies and iconic themes, accompanies the action with a dynamism that is almost a character in itself, amplifying the epic sense of adventure and the melancholic sweetness of the more intimate moments.

Among the most memorable scenes: the concert at the school dance where Marty, to re-establish the correct course of events, must make his father and mother fall in love, as she has instead fallen for him. During the performance, Marty launches into an electric guitar solo with an inevitable metal riff, and while everyone remains dumbfounded watching him, he candidly apologizes: "Perhaps you're not ready for that yet." This scene is not just a brilliant narrative stratagem, but a meta-commentary on the nature of cultural innovation. Marty, the kid from the future, brings pure rock 'n' roll, not yet mediated by 1950s pop, a foretaste of what music would become. It is a moment of brilliant anachronism that culminates in an implicit homage to Chuck Berry – Marvin Berry's cousin, who, inspired, calls Chuck to let him hear "that sound" – creating a virtuous cycle that links the past to the future through music. It is in these moments that Back to the Future transcends simple entertainment to become a work of art that reflects on history, identity, and the cathartic power of creativity.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...