Being John Malkovich

1999

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

From a Charlie Kaufman concept, a surreal, parodic, grotesque story that unfolds like a labyrinth of the unconscious mind's mirrors. Kaufman, a demiurge of screenwriting, here orchestrates one of his most audacious dissections of identity and the human condition, anticipating themes he would later explore with obsessive lucidity in subsequent works like Adaptation. and Synecdoche, New York. His cinema is a constant questioning of fiction and reality, of the mask and the authentic self, a territory where existential unease merges with disruptive comedy and astonishing intelligence.

A subconscious comedy staged with great self-deprecating verve by an astonishing John Malkovich, a greatly talented actor who, for the first time, is the main subject of a film, becoming, so to speak, its narrative lynchpin and simultaneously its performer. His performance is not only a demonstration of humility and playful spirit in parodying his public image, but a true metanarrative exploration of the concept of celebrity and its appropriation by the public. Malkovich lends himself to being a vehicle, a canvas onto which others' fantasies and desires are projected, embodying an ambiguity and vulnerability that make his character deeply, and comically, pathetic.

An intelligent and genuinely brilliant director like Spike Jonze takes a story hovering between dream and absurdity and presents it to us with the naturalness and spontaneity of a verismo melodrama seasoned with a dash of Kafka and a Dadaist nuance. Jonze, with his refined but accessible aesthetic, partly derived from his previous experience in music videos, where he had already demonstrated a surprising ability to evoke inner worlds (think of his works for Björk or the Beastie Boys), transforms the Kafkaesque abstraction of alienating bureaucracy and non-sense into a visceral experience. Dadaism is not just an accent, but the very matrix of the operation: a playful deconstruction of logic, an invitation to laugh in the face of absurdity, subverting every narrative and visual expectation. The celebrated "seventh-and-a-half floor," with its claustrophobic ceiling, is not just a surreal detail, but a powerful metaphor for modern existence, crushed by invisible constraints and oppressive conformity.

Craig Schwartz (John Cusack) gets an office job at an archival company located on the seventh-and-a-half floor of a New York skyscraper, thus halfway between one floor and the next with a very low ceiling (so low that those who work there must walk hunched over).

The man discovers, behind a heavy metal filing cabinet, a tunnel that leads to the mind of John Malkovich. Anyone who enters the passageway will have fifteen minutes to enter Malkovich's mind and live his life for that precise span of time. Then they will be ejected, ending up in a highway ditch in New Jersey. This premise, itself striking, opens an abyss of questions about identity, its fluidity, and our insatiable hunger for the appropriation of the other. It is the apex of voyeurism, the definitive colonization of another's consciousness, an experience that goes far beyond simple cinematic immersion, transforming the viewer not just into an observer, but into a celebrity parasite. The "highway ditch" is the comical and brutal epilogue to this intrusion, a return to banal and degrading reality.

Craig tells his wife Lotte about it, who wants to experience the thrill of being John Malkovich. She will be so disturbed by it that her sexuality will irrevocably change. Lotte's transformation is not just a narrative twist, but a courageous exploration of gender fluidity and desire, which emerges when the boundaries of the self dissolve. Malkovich's mind becomes a laboratory for self-discovery, however distorted and surreal it may be.

Meanwhile, the beautiful Maxine, Craig's colleague and whom he is secretly in love with, also learns about the tunnel.

From this point forward, the story will become quite complicated, with the two women experiencing an irresistible sexual attraction to each other via the conduit of Malkovich's mind. This dynamic not only subverts the narrative conventions of the love triangle but boldly explores the fluidity of desire and the performative nature of sexuality. Malkovich's body becomes a bridge, a catalyst for a love that transcends gender and identity barriers, posing provocative questions about the true nature of attraction and the essence of the individual beyond their physicality.

Finally, John Malkovich himself will learn about the mental tunnel and try it with hilarious effects.

Jonze's skillful directorial setup allows the surreal element to traverse the territory of normality and emerge naturally and without any forcing, as if it had always been inherent in daily experience. The film thus positions itself within the current of postmodernism, where metanarrative play and the deconstruction of reality are not ends in themselves, but tools to probe the depths of identity and desire in the era of technical reproducibility.

The fact that this Surreal interacts with conventional narrative elements creates a sense of estrangement in the viewer, a suspension of pragmatic judgment, a loss of reference points. We are led into a labyrinth where Cartesian logic is suspended, yet everything seems strangely coherent within its own bizarre rules.

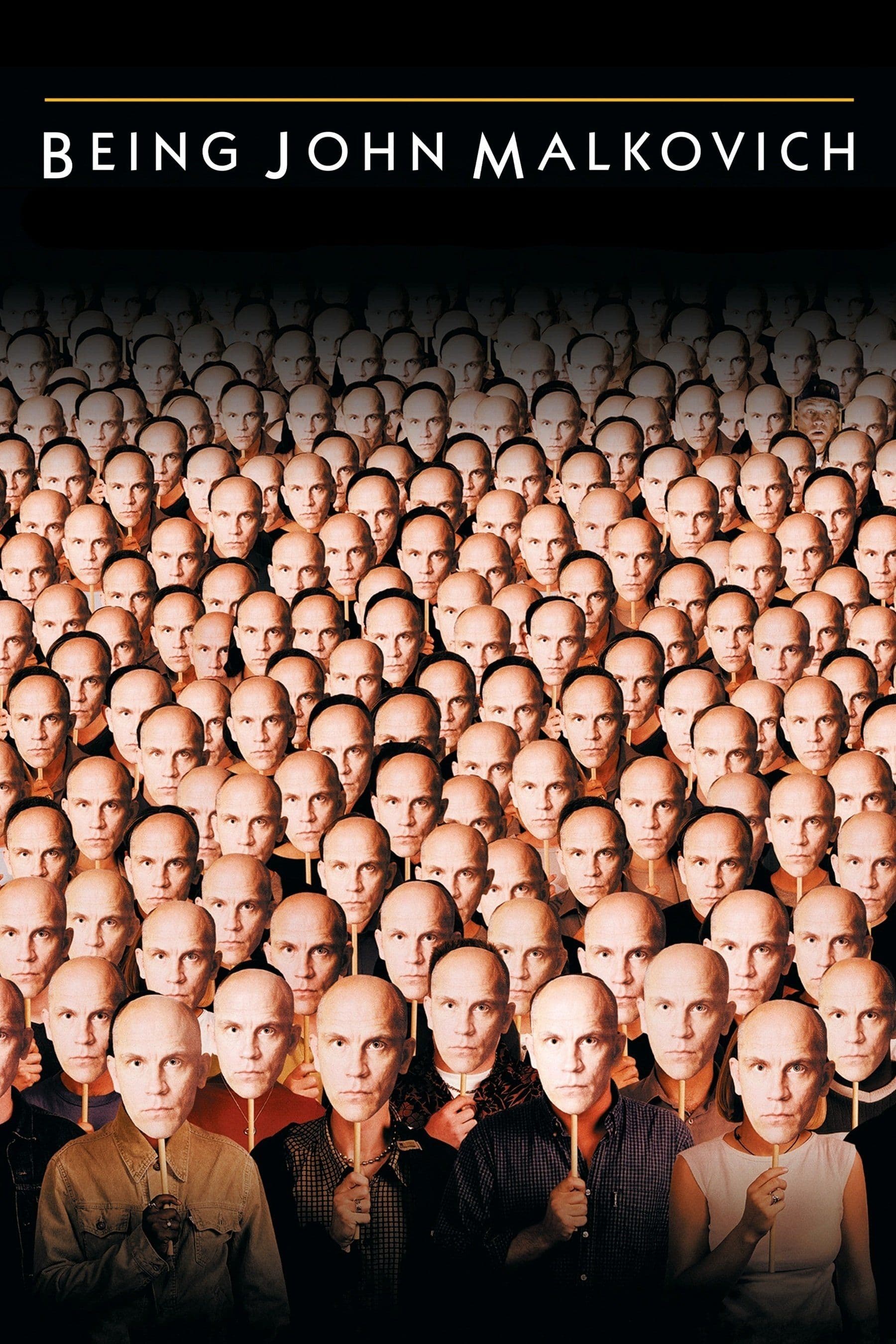

Truly memorable is the scene where John Malkovich enters his own mind through the passageway, creating a kind of tear in the logical fabric of Reality and ending up in a world where everyone is John Malkovich and where every form of written and spoken language is limited to the word "Malkovich." This is the metatextual culmination, a self-aware delirium that encapsulates the entire message of the film: the artist, or in this case the celebrity, is condemned to be endlessly reproduced and consumed, trapped in a parody of themselves. It is the definitive implosion of the concept of "self," a mocking echo of Plato's cave but with a postmodern twist, where the shadows are merely the infinite replicas of the Malkovich-brand. Its impact, both intellectual and comedic, is devastating, leaving the viewer in a mix of wonder and disorientation. Brilliant, and very entertaining, Being John Malkovich is not just a film, but a unique experience of deconstructing the self and cinema itself, an ironic warning about our perennial search for identity in an increasingly mediated and fragmented world.

Country

Comments

Loading comments...