Being There

1979

Rate this movie

Average: 1.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

Chance the gardener is a creature instantly lovable, from the very first shot. He is not merely a character, but an archetype whom Ashby, with his unmistakable sensibility, molds like docile clay, shaping an indecipherable personality, almost zen in his fierce daily routine marked by TV, watering roses, and dusting the car. Not a mere representation of autism in the clinical sense, but rather the embodiment of a pure mind, a tabula rasa that rejects the complexity of the civilized world, or perhaps is simply not equipped to decipher it. He is an unwitting hero who, with his absence of malice and superstructures, unmasks the empty rhetoric and hypocrisies of power and the media.

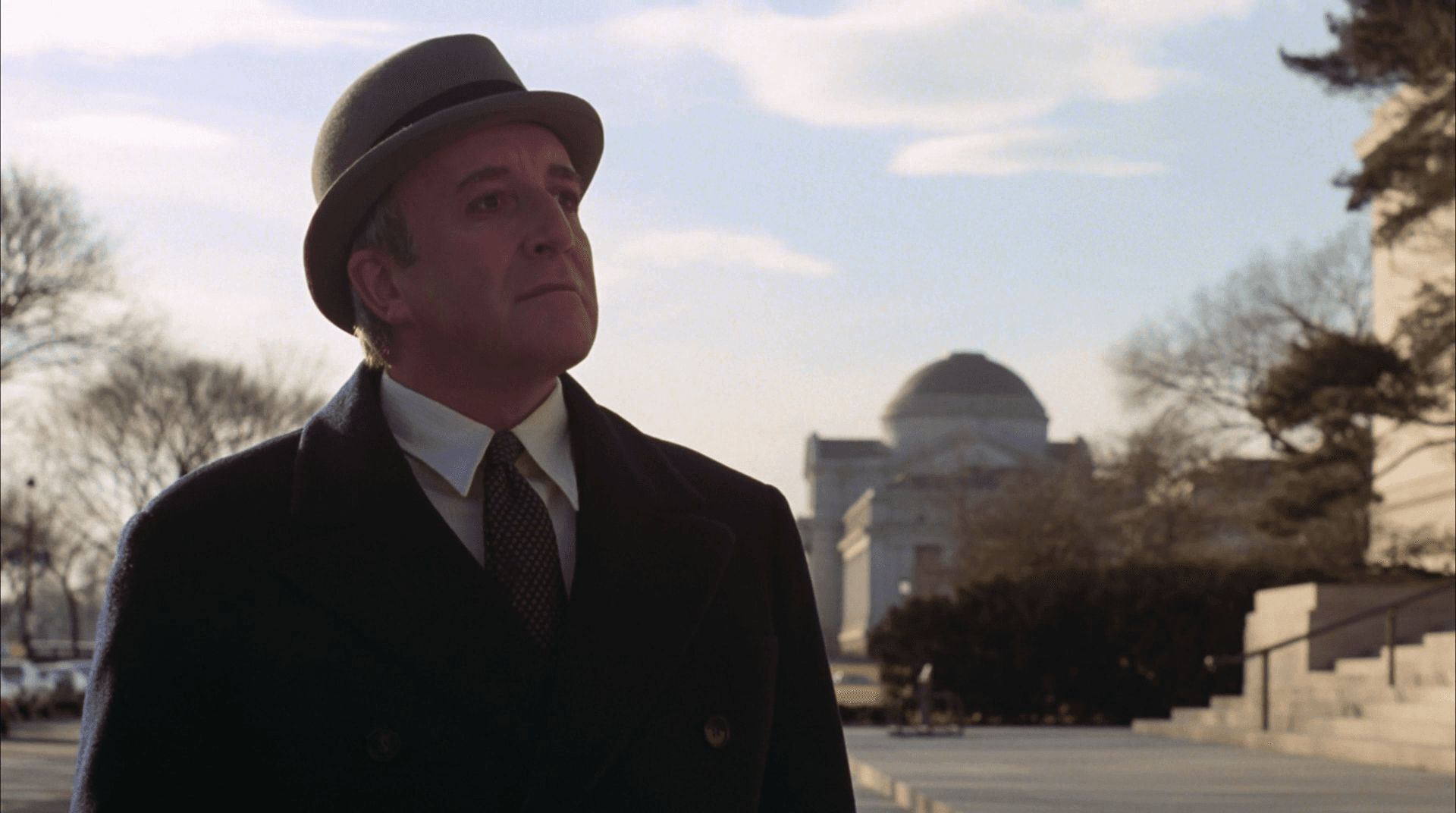

Peter Sellers embodies this grotesque man, becoming his ineffable mask, a masterpiece of actorly subtraction. It is not the slapstick comedy of his Inspector Clouseau, nor the brilliant schizophrenia of Dr. Strangelove; here Sellers nullifies himself, becoming a transparent shell through which Chance's simplicity filters unhindered. It is said that Sellers, obsessed with the role, spent months perfecting the character's voice and cadence, reducing it to a monotone whisper, almost devoid of inflections, a timbre that reflected his mind stripped of all superfluous complexity. His fragile health at that time, which would lead to his premature death shortly thereafter, imbued the character with a melancholic patina, almost a premonition of the end awaiting him, making his performance even more poignant and unforgettable.

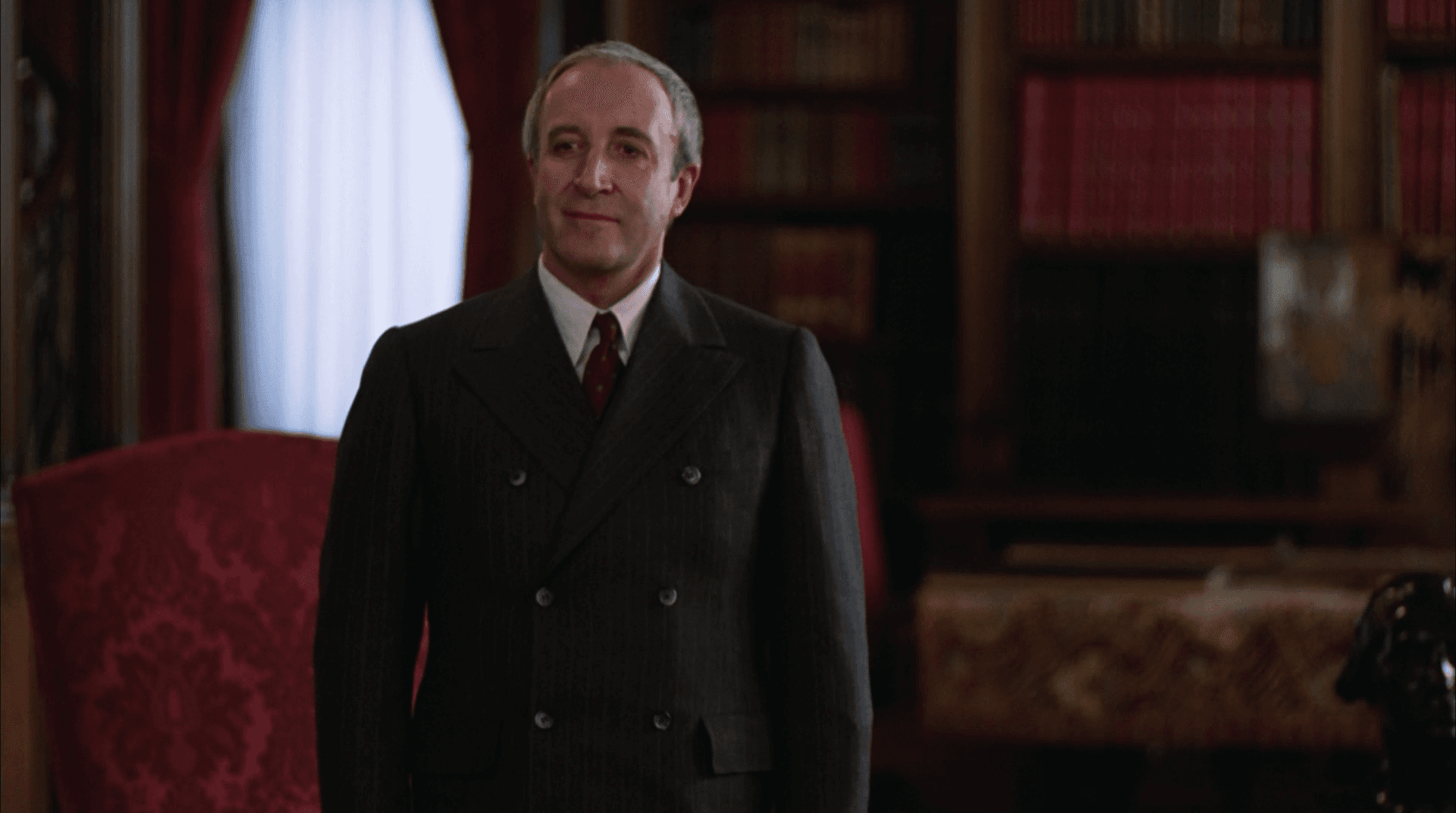

We will follow Chance's adventures as he, from his humble role as a handyman gardener, becomes, from one misunderstanding to another, the right-hand man of the President of the United States, mistaken for an incomparable genius. This happens thanks to Chance's ability to endear himself to people, thanks to his innate candor, his tender propensity for nature, for what grows from the earth, his total lack of irony, and, above all, thanks to society's pathological tendency to project its craving for complex answers onto simple individuals. His agricultural metaphors, born from the genuine observation of the plants' life cycle, are interpreted as profound economic and political allegories, a bitter commentary on the superficiality and emptiness of public debate, an echo of "the emperor's new clothes" draped upon a man who has nothing to hide because he has nothing to declare. Television, in particular, is the key element of this ascent. The medium that Chance had always only passively absorbed becomes the vehicle for his unexpected celebrity, transforming him from a mere spectator into an unwitting protagonist, a sharp commentary by Gore Vidal, author of the original novel, on the manipulative power of the magic box during its period of maximum expansion.

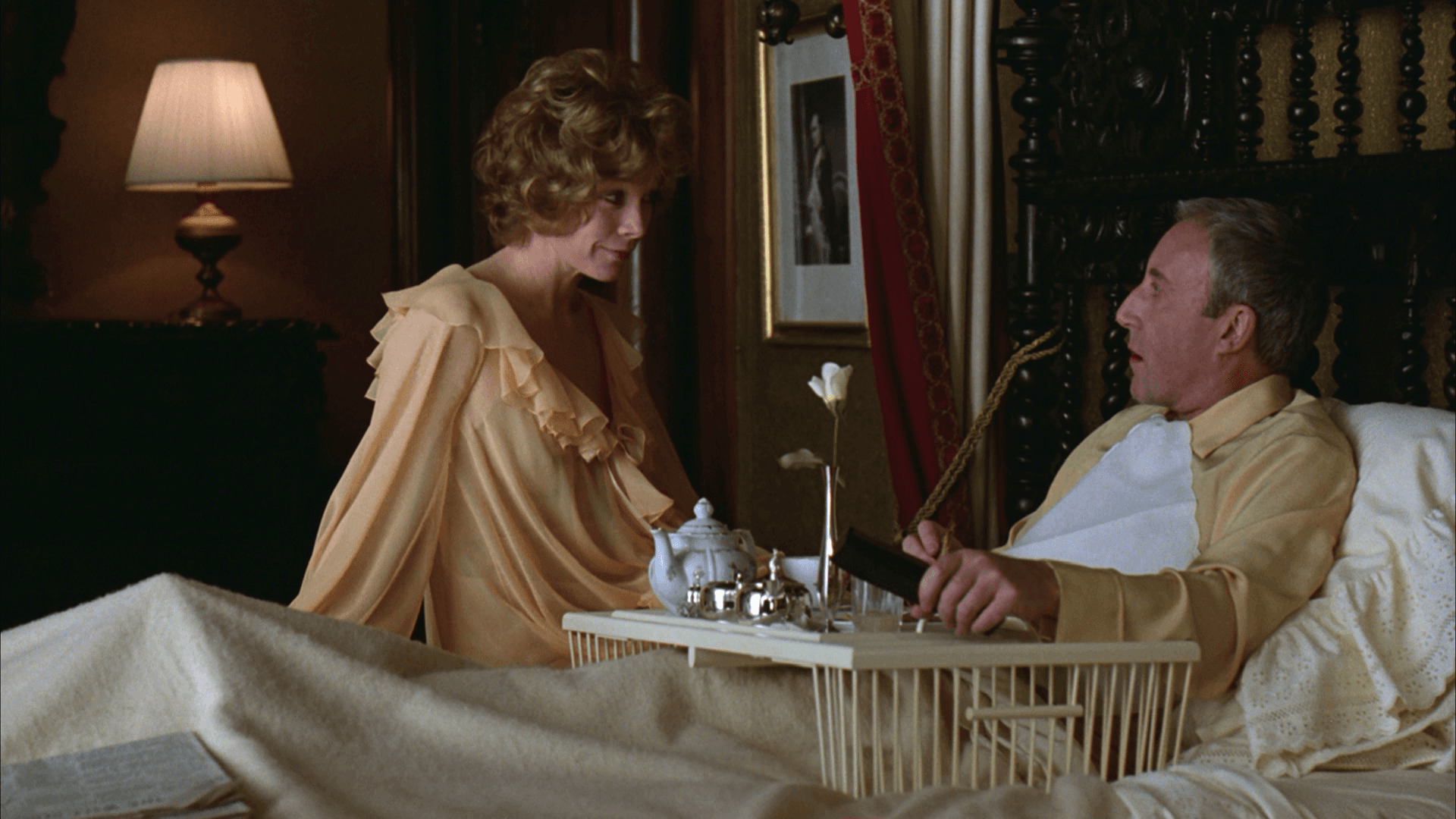

He thus befriends Ben, an influential friend of the President of the United States, becoming a kind of spiritual advisor to him. The relationship between Ben and Chance is one of the film's gems: Ben, a man of power worn down by his own responsibilities, finds in Chance not a guru, but a mirror in which his weariness and his search for authenticity are reflected without filters. It is a bond that transcends conventions, an oasis of mutual incomprehension that paradoxically becomes profound understanding. Ashby's direction, a master at capturing human nuances, lingers on these moments of apparent stillness, charged with subtle humor and intrinsic melancholy.

Upon Ben's death, while Ben's last wishes are being read at the funeral ceremony, Chance is distracted by a small pond. Approaching it, he walks upon the water's crystalline surface with grace and lightness, a perfect metaphor for a life without double meanings, without moral gravity, a lightness of being that defies the laws of physics and materialism. This final scene, of iconic beauty and rare symbolic significance, has been the subject of countless interpretations. Is it a divine miracle? A collective hallucination? A mere optical effect that Chance, in his innocence, does not perceive as such? Or perhaps, the most radical of interpretations, it is proof that Chance truly is what others have projected onto him: a superior being, not in the sense of an intellectual genius, but of a liberated soul, beyond earthly conventions and expectations. Ambiguity is his strength, his deepest essence. Meanwhile, in the background, Ben's monologue concludes with the phrase “Life is a state of mind,” a closing remark that resonates as a prophetic echo and an epiphany for the viewer, suggesting that reality, and life itself, are shaped not by objective facts, but by individual perception and interpretation. And Chance, in this sense, is the living embodiment of this philosophy.

Memorable, as has been said, is Peter Sellers' performance in his penultimate appearance before a cursed heart attack at the age of fifty-four snatched him from us forever. This film, released in 1979, stands as a pinnacle of New Hollywood, a golden age of American cinema that dared to tackle complex themes with audacity and originality. Hal Ashby, with his sober yet incisive style, delivers a work that, while operating within the register of satirical comedy, proves to be a keen and dispassionate analysis of contemporary society, politics, and the role of the media. "Being There" is not just a film; it is a work to smile at and to decipher ourselves through the clear eyes of a simple mind of infinite candor, a timeless admonition on the importance of looking beyond appearances and rediscovering purity in a world obsessed with complexity.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...