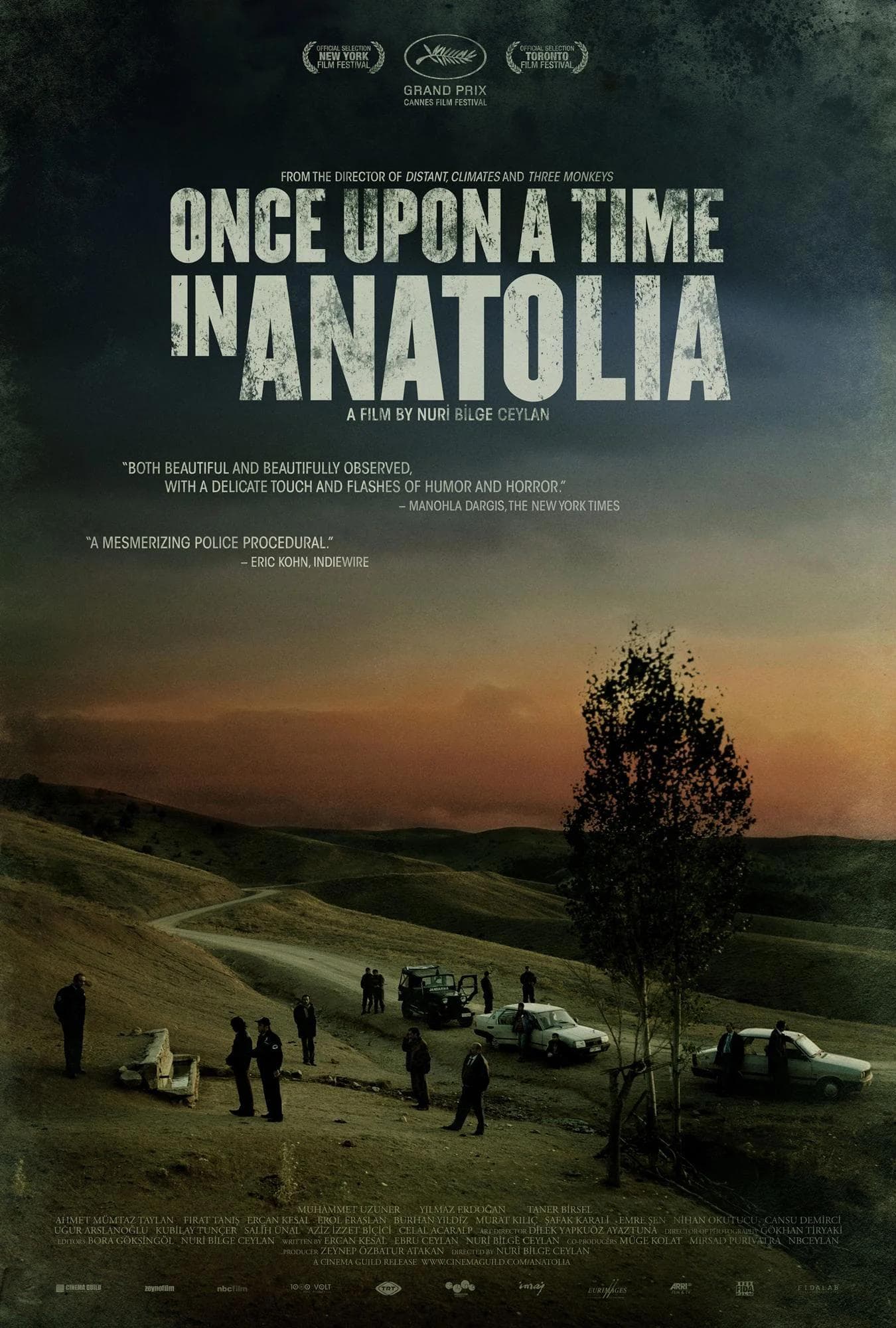

Once Upon a Time in Anatolia

2011

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Turkish director Nuri Bilge Ceylan takes the structure of a genre (the crime film) and slows it down to a near standstill, emptying it of all conventional suspense and filling it with an almost unbearable existential weight. It is a work that demands unconditional surrender from the viewer, a total immersion in an expanded time and space, where a journey of a few hours across the Anatolian steppe becomes an odyssey into the nighttime soul of man. It is an existential western, a journey to the end of the night, whose viewing is as demanding as it is, in the end, deeply rewarding.

The shadow of death is everywhere, right from the first frame. It stretches from the top of a hill and a valley to the souls of the characters, men forced to wander in the darkness in search of a corpse. The first part of Once Upon a Time in Anatolia is exactly like that: cold as death, calm as death, and dark as death. In this nocturnal procession of cars cutting through the darkness with their headlights, creating islands of ephemeral light in an ocean of black, one senses the influence of the great masters of contemplative cinema. The cinematic references in Ceylan's work to the works of Abbas Kiarostami and Andrei Tarkovsky ensure that this “shadow of death” hovers over us. From Kiarostami, Ceylan takes the idea of the car as a privileged cinematic space, a mobile confessional where the most banal conversations are charged with profound meaning. From Tarkovsky, he inherits the ability to film the landscape as a spiritual entity, a magnificent and indifferent nature that mirrors and counterbalances the small and tragic events of human life.

The second half of the film, which takes place in the gray light of day, is a clear struggle between what we see on screen and what we perceive from the narrative. The night, with its mysteries and shadows, is over. Now there is the harsh reality of the body, the autopsy, the bureaucracy. There is no visual sign of death as such, in the sense of an action or a dramatic event, but its meaning persists, so much so that the night is not yet over, or in other words: death does not need you to see it with your own eyes, it can make its presence felt in the depths of your existence, even under the most merciless light. Ceylan's work is a masterful display of death as a permanent condition, whether we are aware of it or not, whether it is the dark of night or the light of day.

This obsession with mortality and with the journey as a descent into hell binds the film inextricably to a certain literary tradition. If one must seek a spiritual godfather for this nocturnal caravan, it can only be Louis-Ferdinand Céline. Ceylan's film is an Anatolian Journey to the End of the Night. There is the same existential weariness, the same wandering through a landscape stripped of all illusion, the same conversation that becomes a vehicle for a profound cosmic pessimism. The characters (the doctor, the prosecutor, the police commissioner) talk to fill the silence, to fight fatigue and darkness, and their stories and anecdotes are small windows onto a world of pain, regret, and absurd randomness. Death, as in Céline, is not a tragic and culminating event, but a fundamental condition, the white noise that accompanies our entire existence.

But then, what is the powerful metaphor hidden behind this seemingly simple plot? The search for the corpse is, in reality, the search for Truth in a world that lacks it. The buried body is the only presumed certainty, the objective fact around which the entire investigation revolves. But the journey to find it reveals that every man in that caravan is carrying his own buried corpse: a secret, a remorse, a personal tragedy. The prosecutor tells the disturbing story of a woman who died in mysterious circumstances after predicting the exact day of her death. The doctor, our main point of view, is a divorced man haunted by the ghost of a past mistake. The commissioner is plagued by family problems. The external search for the body becomes a pretext for an inner descent into their fragmented lives. The truth they find in the end is not the resolution of a police case, but a more bitter and complex truth about human nature.

The second part of the film, with the arrival in the town and the autopsy, is a masterful autopsy of truth itself. The poetic and metaphysical night gives way to the clinical and brutal prose of science and bureaucracy. Yet even here, certainty is an illusion. During the autopsy, the doctor, the man of reason, notices a terrible detail: there may have been dirt in the victim's lungs, which means she may have been buried alive. The objective truth, once found, proves even more horrific and ambiguous. But the real heart of the film, the moment of unexpected grace, comes when the doctor is confronted by the victim's widow. Ceylan's camera lingers on the woman's beautiful, dignified face as she serves tea, and then on the face of the doctor watching her. In that silent, prolonged exchange of glances, a whole universe of untold stories, shared pain, and a fragile and sudden human connection passes by. In that moment, the film transcends cynicism and despair and strikes a note of pure, heartbreaking empathy. It is a masterpiece that uses slowness as a moral tool, forcing us to watch, feel, and think. It offers no solutions, but, like the apple rolling down a hill in one of its most beautiful scenes, it shows us the unexpected beauty and sad inevitability of our journey into darkness.

Countries

Gallery

Featured Videos

Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...