Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

1966

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

Mike Nichols brings theater to the big screen, not merely a transposition, but an operation of audacious and perceptive cinematic distillation from Edward Albee's titanic play. It was 1966, an era of transition for Hollywood, where moral codes were starting to creak and an opening emerged for a more adult, more ruthlessly truthful cinema.

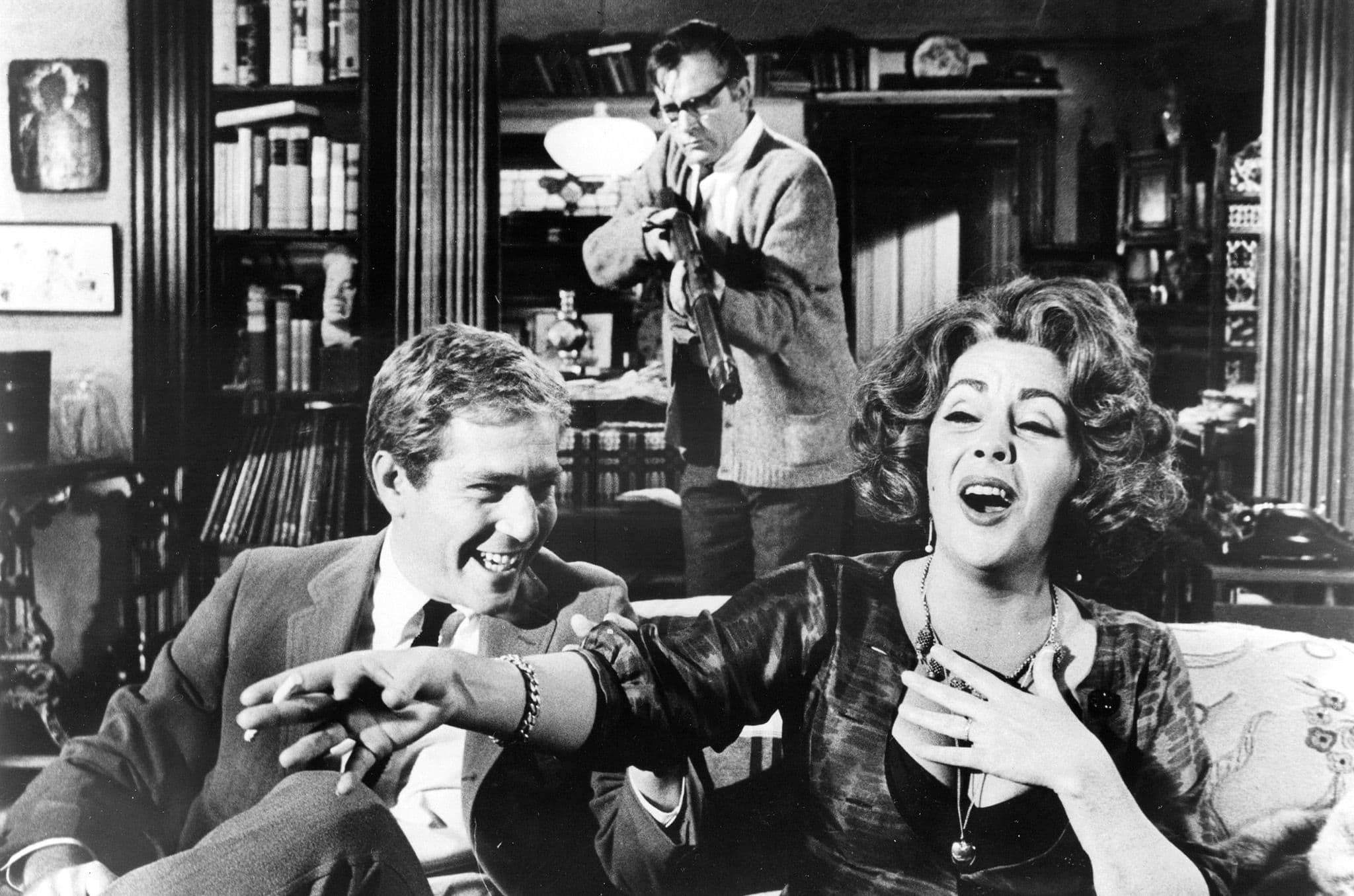

This is a risky operation, almost a productive and artistic gamble, but one that proves to be of disturbing fascination and undeniable depth. Nichols' audacity lies not only in tackling such a dense and verbose text, but in visually shaping it, elevating the scenic claustrophobia to an almost metaphysical dimension. And, certainly, the triumph is largely ascribed to the two splendid protagonists of this two-voice drama: Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton.

The physical sensation of this film's theatricality is felt from the first shots: obsessive, almost fixed, with unity of place, time, and action that recall Aristotelian rigor. Yet, Nichols, with the complicity of Haskell Wexler's masterful cinematography – a raw, sculpted black and white that strips away any veneer of glamour to reveal the bare, almost spectral, reality of human relationships – manages to transform the limitations of a single nocturnal setting into a claustrophobic nightmare where the walls seem to tighten around the characters like a vise, amplifying their inexorable descent into domestic hell. The chiaroscuro, far from being an economic choice, becomes an essential narrative tool, emphasizing the ambiguous morality and psychological grey areas of the protagonists.

The story is about a cohabitation at the limit of human possibility between George, a university History professor whose field of study almost ironically reflects his inability to progress and confront the present, and his wife Martha, a cynical, vulgar, and alcoholic woman, whose temperament is as explosive as her unconfessable need for love and recognition. Amidst vitriolic exchanges, soul-piercing stabs, and furious quarrels – veritable verbal duels to the death – unfolds their great little drama of life within domestic walls, a battle arena where love has transformed into a perverse form of psychological sadomasochism. It is a marriage that has never generated life, except that of ghosts and illusions, and which now feeds on mutual destruction, dragging the young and unprepared guest couple, Nick and Honey, into this toxic vortex as sacrificial victims on the altar of their pathological intimacy.

A delightful quip inserted into the screenplay, almost a self-ironic wink, manifests in an emblematic scene: as the two arrive in what should be a hotel room (in reality a narrative subterfuge, George and Martha's house is the only true stage), Martha exclaims that the room is a dump, in fact she seems to be searching for a more incisive definition but can't quite recall it: "It was in a movie, by that frog Bette Davis. One of those usual Warner Bros. potboilers!" The film she refers to is “Sin” (original title: Beyond the Forest) from 1949, by George Cukor, starring Joseph Cotten and, indeed, Bette Davis. It is worth noting that “Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” was also produced by Warner Bros., making the homage even more stratified and, in some ways, subversive. It's a line that not only plays on cinematic intertextuality and the archetype of the melodramatic "diva," but subtly alludes to a break with past melodramas: this Warner film is not an evasive "potboiler," but a raw, unfiltered exploration of the depths of the human soul, a work that defied censorship and paved the way for a new era of American cinema.

But the true living flesh of the film pulsates through the monumental performances of Taylor and Burton. Their chemistry, already legendary due to their tempestuous real-life relationship, is here amplified into a symphony of hatred and desperate love, of dependence and repulsion. Taylor, who intentionally gained weight and made herself look unattractive for the role, offered a Martha of devastating power, a volcano of frustration and ferocity, but also of a harrowing vulnerability that only manifests in moments of extreme exhaustion. Burton, for his part, embodies a worn-out, passive-aggressive George, whose intelligence has been stifled by years of recriminations and failures, but who, when provoked, can hurl poisoned darts with lethal precision, revealing his perverse mastery in the game of slaughter. They are not just actors playing a part; they are two damned souls mirroring and destroying each other, in a macabre dance that is both repellent and irresistibly magnetic.

The film, beyond its circumscribed narrative, is a scathing critique of the illusion of the American dream, particularly the academic one, where intellect should flourish but ends up rotting in mediocrity and disillusionment. The struggle between George and Martha is also a struggle between truth and illusion, between the raw reality of their failures and the comforting fantasies they have constructed for themselves, culminating in the revelation of their imaginary "son," an act of simultaneous creation and destruction that serves to protect and torture them. This theme of illusion is deeply Albee-esque, and resonates with the existential malaise that permeated post-war Western culture, questioning bourgeois values and the facade of respectability. Indeed, it was a film that did not shy away from showing vulgarity and verbal brutality, breaking linguistic and thematic taboos that the rigidity of the Hays Code had maintained for decades. Its release marked a point of no return, contributing significantly to the birth of the MPAA classification system, replacing preventive censorship with a more permissive but sensibility-conscious "rating" system.

Ultimately, “Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” is not just a work that provides a valuable contribution to psychological and introspective cinema, but a true cultural watershed, a manifesto of a cinema that dared to look beyond appearances. It is the kind of film that looks into people's souls and strips them bare for our eager eyes as spectators, not merely observing the surface, but digging into the deepest wounds, the unconfessed desires, the atavistic fears that animate the pathological union of two individuals. It is a cinematic experience that lingers long after viewing, a bitter and powerful echo on the destructive and indissoluble nature of love, when it transforms into a prison of resentment and shattered dreams, and on the fragile illusion we often call reality.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...