Five Easy Pieces

1970

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Robert Dupea had it all: a wealthy family and a promising future as a brilliant pianist. Yet the man leaves everything behind for a job in the oil fields and a more-than-ordinary life far from home. A choice that, at the time of the film's release in 1970, resonated with an almost iconoclastic resolve, embodying the spirit of an entire generation poised between youthful rebellion and the inescapable confrontation with reality. It is not simply an escape, but an act of radical abjuration of a preordained destiny, a silent declaration of war against bourgeois conventions and the suffocating legacy of an upbringing focused on perfectionism and excellence. His decision to immerse himself in a proletarian existence, amidst the fumes of oil rigs and the vulgarity of a motel, is a desperate attempt to free himself from a gilded cage, to find a raw authenticity that his original environment denied him. This radical renunciation immediately positions him as an embodiment of the disillusionment that permeated post-1968 America, an America that was beginning to doubt its own foundational myths.

When his sister calls him back to Washington due to their father's serious illness, it will be an opportunity to revisit his past and unravel the psychological origin of his choices. This return home is not a pilgrimage but a forced immersion into a past never truly buried, an archaeology of the soul that forces him to confront the ghosts of an upbringing as privileged as it was oppressive. The family estate, a sanctuary of art and discipline, becomes the setting for a silent reckoning, where each member embodies an aspect of his flight: his sister Partita, also a pianist and a figure of resigned excellence, the personification of the path Robert rejected; his brother Carl, a musician stuck in the role of family caretaker, a figure of stagnation and passive acceptance; and his father, the primal source of that suffocating pressure that drove him adrift. There, amidst lavish furnishings and rarefied conversations, the air thickens, and Robert's motivations are revealed not as a mere whim, but as the consequence of a visceral rejection of an imposed identity, of a role that would have stifled him like a garment too tight.

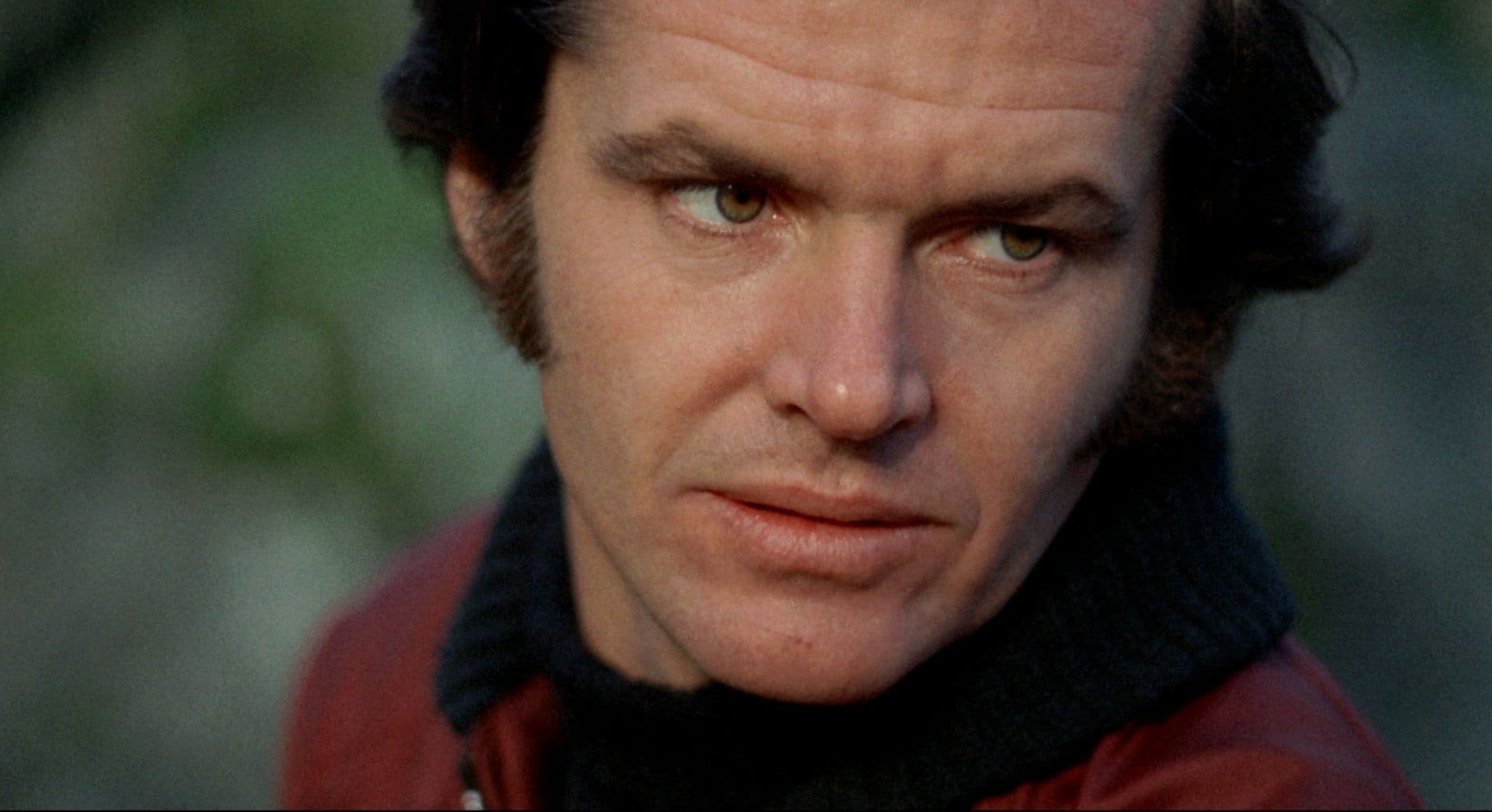

Jack Nicholson is fantastic in the lead role, imbuing the character with a disturbing and somewhat mystifying depth. This performance, which earned him an Oscar nomination, is not just a masterful acting; it is the affirmation of an archetype, the definitive consecration of Nicholson as the quintessential anti-hero of "New Hollywood." His Robert Dupea is a tormented man, capable of ferocious outbursts of anger and moments of unexpected tenderness, a repressed volcano threatening to erupt in every shot. The actor imbues the character with a unique blend of seductive charisma and an almost pathological unease, making him simultaneously fascinating and repulsive. He is not a tragic hero in the classical sense, but rather a rebel without a compass, a wandering soul who carries the burden of acute intelligence and an unbridgeable solitude. His nervous gestures, his evasive glances, his sardonic smile that often masks an abyss of disdain and melancholy, all contribute to building a psychological portrait of rare complexity, elevating the film from a simple drama to an epoch-making character study, a warning about the fragility of the modern soul.

Bob Rafelson in the director's chair delves into his character, laying bare his weaknesses and virtues, in a Freudian manner, with a detached, analytical, almost scientific method. This approach is Rafelson's stylistic hallmark and that of the "New Hollywood" movement, of which he, along with Bert Schneider and Stephen Blauner, was one of the founding pillars with their legendary BBS Productions. BBS, an anomaly in the studio system of those years, gave directors almost total creative freedom, allowing for the emergence of deeply personal and disillusioned works, far from the extravagance and optimism of previous decades. Rafelson, with Five Easy Pieces, adopts a gaze that is both empathetic and unsparing, perhaps inspired by the existential alienation of Antonioni or Bergman's films, but placed within a deeply American context, that of on-the-road wanderings and marginal existences. His direction does not judge, but observes, allowing interactions and silences to reveal the protagonist's inner fractures, as in an analysis session where the patient, while refusing to open up, exposes every raw nerve through their behavior. The narrative proceeds in fragments, almost as if to reflect Robert's disconnected life, a mosaic of fleeting encounters and temporary places that amplify his sense of existential precariousness.

A fascinating, refined, introspective film. The title itself, Five Easy Pieces, is a subtle and poignant metaphor. It refers to the basic piano exercises that Robert, in a moment of frustration and anger, performs only to then reject them with contempt, emblematic of his inability or reluctance to face life in its simplest and most immediate forms, preferring (or being condemned to) a self-imposed complexity, an inner torment that he himself fuels. This is a film that probes not only the psyche of an individual but the human condition itself in post-hippie America, an era in which grand narratives were fading and the individual found themselves alone before their own nihilism and responsibility. It is a work that, with its melancholic elegance, questions us about the nature of happiness, the meaning of freedom, and the price of authenticity, suggesting that often, even while desperately seeking it, we ourselves preclude the possibility of attaining it. The camera moves with an almost choreographic grace, capturing the immensity of the American landscapes that serve as a mirror to the vastness of Robert's inner void, from the desolate flatness of California's oil fields to the cold and distant elegance of the Washington islands.

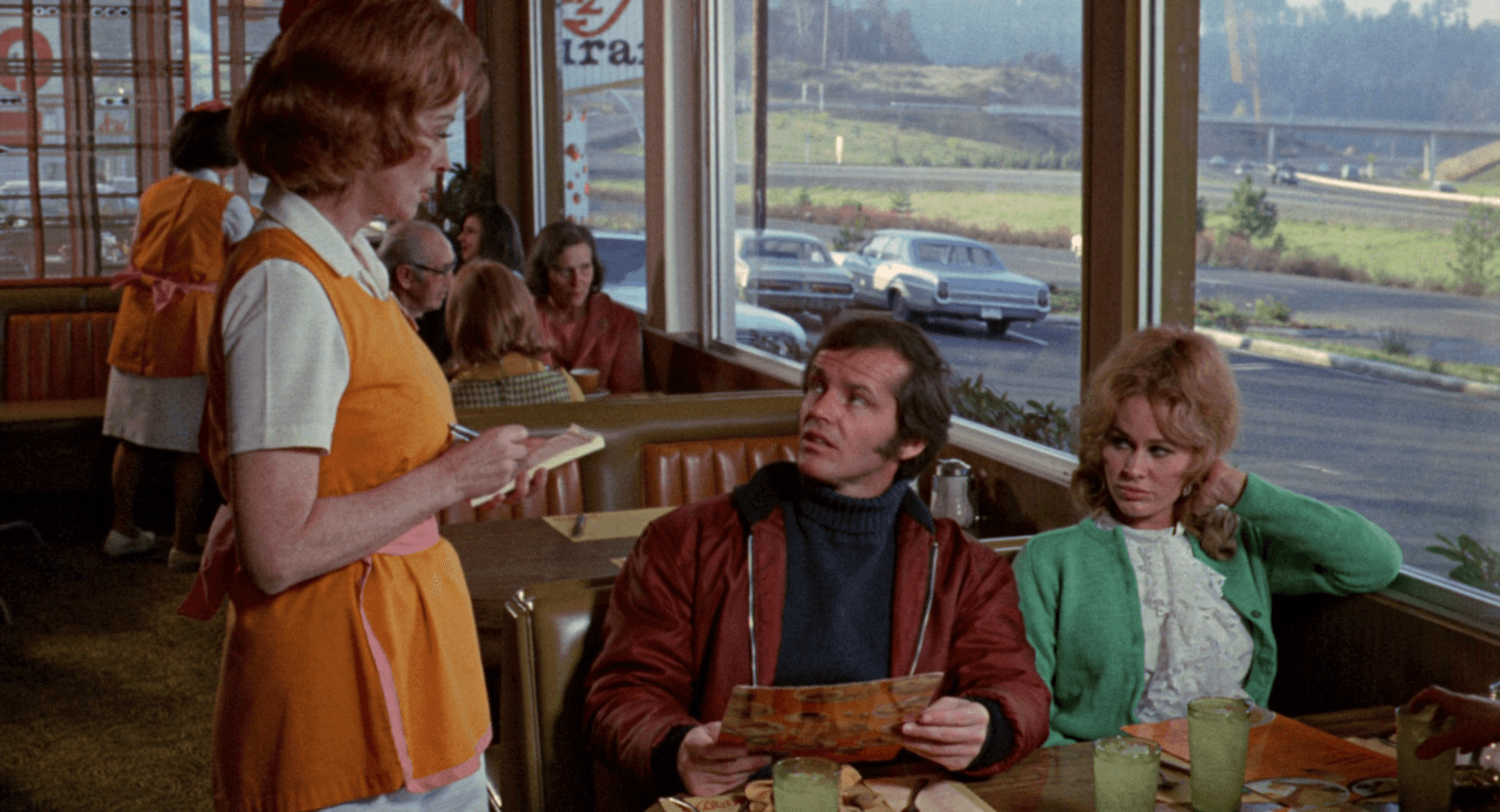

A work entirely focused on the figure of a character who is fundamentally an outcast who abandons and cannot return to his life because he is caught in an invisible net of intolerance towards humanity. This "invisible net" is not so much an external obstacle as an internal barrier, a wall erected by Robert himself between himself and the world, a kind of intellectual misanthropy that prevents him from any true connection. His intolerance is for banality, for superficiality, for the intellectual and emotional limitations of others. It is an elitism disguised as contempt for the bourgeoisie, but which ultimately traps him in an ivory tower of solitude. The iconic restaurant scene, where Robert clashes with a waitress over the possibility of ordering a side of toast with his chicken sandwich, is a microcosm of his inability to compromise, his intolerance for the small, petty rules of communal living. It is not just the request for a piece of toast, but a declaration of war against obtuseness, a challenge to the mediocrity that surrounds and suffocates him. At that moment, Robert Dupea is not just an irritated customer, but the symbol of an entire generation that, while yearning for freedom, finds itself unable to truly connect with it, a prisoner of its own idiosyncrasies and its, at times unbearable, moral and intellectual superiority.

Indeed, there isn't a single scene in the entire film where Robert is at ease with the people around him; this makes him a kind of loser ante litteram, a sociopath adrift in the great sea of life, attempting in every way to survive himself. The definition of "sociopath" is perhaps too strong, but it captures his intrinsic inability to form authentic and lasting bonds. He is more an existential hermit, a nomad of the soul who finds no peace either in the conventions of his past or in the raw authenticity of his present. His final, desperate escape at the end, a gesture of definitive and perhaps self-destructive rupture, aboard a truck taking him God knows where, seals his destiny as an eternal outsider, a man condemned to wander, to search without ever finding, because what he seeks – total freedom, absence of compromise, unblemished authenticity – is intrinsically irreconcilable with human existence and its imperfections. Five Easy Pieces offers no easy answers, nor redemption, but leaves us with the unforgettable portrait of a broken man, a mirror of an America in an identity crisis, a masterpiece of melancholy and disillusionment that continues to resonate powerfully even decades later, an eloquent warning about the complexity of the human desire for authenticity and the intrinsic solitude of those who refuse to conform.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...