Clerks

1994

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

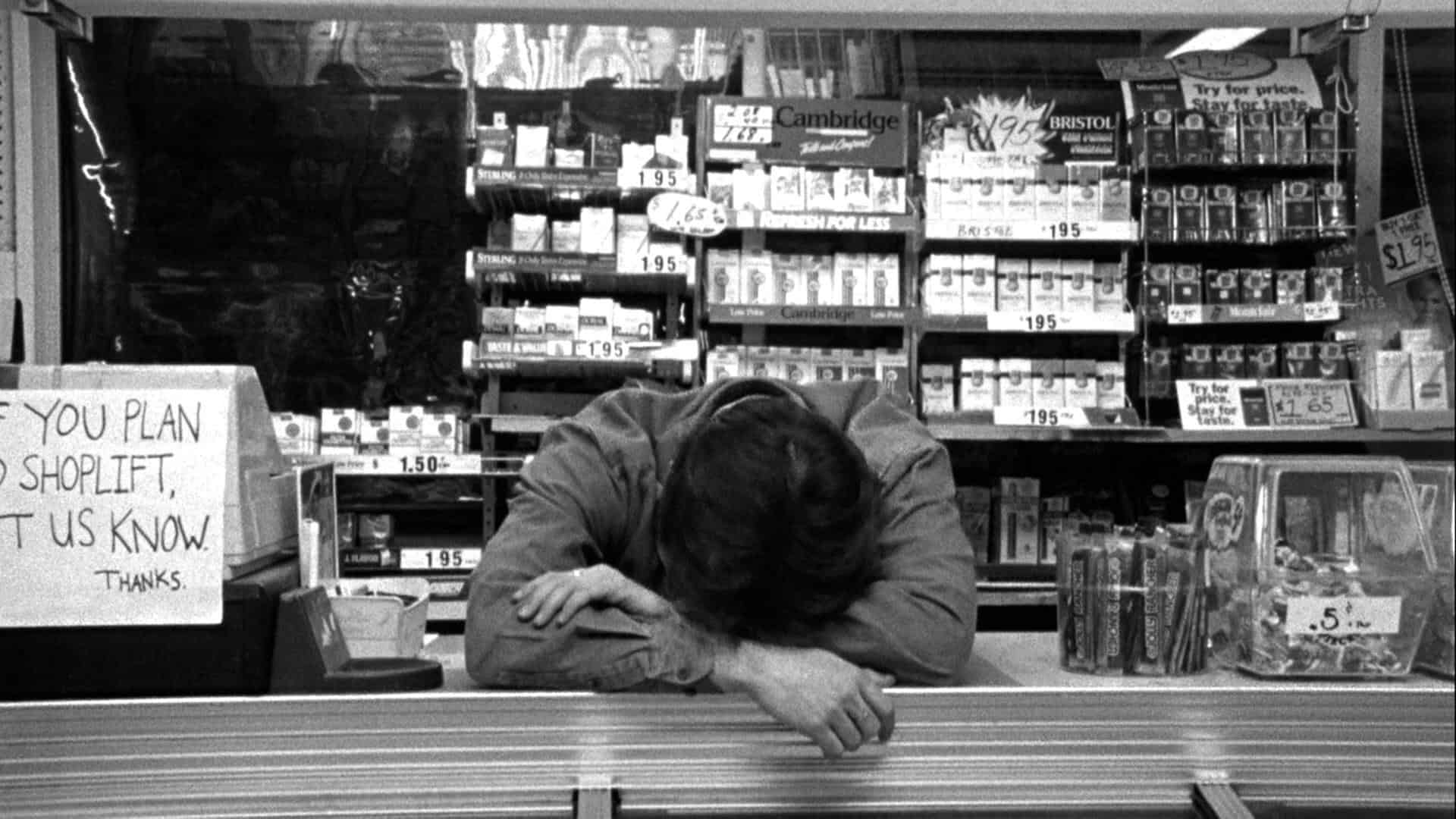

Director

Produced at a very low cost (total budget: twenty-seven thousand dollars, one of the lowest ever) it chronicles a day in the life of a convenience store clerk in a small New Jersey town. A paltry sum, even by the standards of the most extreme independent cinema, which was not an obstacle, but rather a virtue: the grainy black and white, a choice not only economical but aesthetic, lends the film an almost documentary texture, an immediacy that transcends mere representation to become a generational portrait. It is a black and white that evokes urban neorealism, not for epic grandeur, but for its raw honesty in capturing the tedium and small rebellions of everyday life.

Kevin Smith, a debutant director at the time, wrote, produced, acted in, and filmed what is evidently a story pertaining to his personal experience, painting with undeniable emotional participation the personalities of the two main clerks and their bizarre escapades. This was not merely a biographical transposition, but an almost foundational act for what would become his "View Askewniverse", a coherent and irreverent narrative universe that draws directly from the idiosyncrasies of his world and his reference pop culture. Smith, with almost unconscious courage, mortgaged his comic book collection and credit cards to finance this project, transforming an act of financial desperation into a milestone of American independent cinema, a manifesto of the Generation X "slacker" aesthetic, which finds its battle cry against the banality of the working world in existential nihilism and irony.

Effervescent dialogues, a jocular tone in every situation, improbable characters animating the bleak routine of work behind a counter. The true strength of Clerks lies in its biting verbosity and its ability to elevate the trivial to the rank of philosophical discussion. Every line is a stab, a lightning-fast aphorism, a pop culture quote distilled and re-elaborated in a provincial setting. Discussions about the ethics of the Death Star "contractors" in Star Wars or the presumed virtues of oral sex, far from being mere vulgarity, become expressions of a profound existential unease, a search for meaning in a world that seems to offer none. The characters, though on the fringes of productive society, possess an internal logic, however distorted, that makes them strangely fascinating and representative of a counterculture that rejects bourgeois conventions.

These ingredients, along with the director's already accomplished craftsmanship, make this film loved by viewers who quickly identify with the two protagonists. Smith's ability to orchestrate verbal chaos and give a relentless pace to an apparently static plot is proof of an innate talent for storytelling, even in the absence of means. His is a cinema that celebrates the antihero, the chronic procrastinator, the dreamer without concrete ambitions, and does so with a disarming sincerity that creates an almost immediate empathetic bond. Despite their imperfections and often unacceptable reactions, Dante and Randal become universal archetypes of youthful frustration and the desire to escape an oppressive daily life, in a way that recalls the existential angst of certain beat literature, filtered through the aesthetics of the videotape and fast food.

Dozens of memorable scenes; the film is indeed divided into small titled sketches, picking up on a glorious comedic tradition from the genre's beginnings. This structural choice is not random; it evokes the fragmentation of variety theatre, vaudeville, or even early silent comedy films, where autonomous vignettes followed one another to build a mosaic of situations. Each title – "Dante and Randal and a Customer Who Wants Eggs", "The Debate on Whether the Empire Was Evil" – functions as a Brechtian caption, almost a silent film intertitle, punctuating the flow of events and highlighting the intrinsic absurdity of each interaction, transforming the workday into an episodic comedy of the absurd.

The customer searching for the perfect egg, victim of a phobia that leads him to rummage through, feel, and smooth eggs in convenience stores across half the country, only to then discover he is an educational director, a useless professional figure who thus vents his frustration. This scene is a microcosm of Smith's social criticism: the character, seemingly a harmless eccentric, turns out to be a representative of ineffective bureaucracy, whose obsessive-compulsive disorder about eggs is a metaphor for his alienation and his inability to find authentic meaning in life, except through the micro-management of the trivial. His figure is an ironic warning against the futility of certain professions and the emptiness of the lives they create.

The woman desperately trying to capture the clerk's attention about rental films, a clerk who sarcastically ignores her, deriding her cinephile anxiety. This is another touch of meta-cinematic genius. Her eagerness to share a passion, even through the distorted lenses of the most pedantic cinephilia, clashes with Randal's dismissive apathy, who, as a true video store employee, has developed an immunity to the wonder of cinema, reducing it to a mere shelf product. It is a bitter and hilarious portrait of the distance between authentic passion and its commodification, a sketch that unmasks the illusion of "knowledge" as a form of superiority, and the defensive reaction of those who, trapped in routine, reject any glimmer of others' enthusiasm as a threat to their own indifference. Clerks is, ultimately, a monument to the ordinary, elevated to the extraordinary through the keen and irreverent lens of a filmmaker who knew how to find epic scope in a convenience store and philosophy in bar chatter.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...