Control

2007

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Ian Curtis was the beating heart of a band that reached peaks of immeasurable popularity in the English post-punk scene after just two albums. It was not a simple ascent in the charts, but the crystallization of an iconography and sound that would carve an indelible groove in the collective imagination, transcending the brief temporal span of their existence.

Joy Division formed in Manchester in 1977 and disbanded with Ian's death in 1980, leaving behind a trail of mystery and an artistic legacy that continues to resonate—a legacy composed of dissonances and dark harmonies, of words uttered with an almost prophetic gravity.

Control, Anton Corbijn's film, is not a mere tribute, but a true exegesis of Ian's myth and his extremely difficult coexistence with epilepsy and success, two exogenous and endogenous elements that profoundly destabilized his already fragile psychological balance, leading him to suicide in 1980 at just twenty-three years old. The film dives with almost surgical courage into the folds of a strained existence, a precarious thread between the incandescent creative flame and the abyss of a tormented soul. The narration is not limited to a chronological account, but seeks to penetrate the psyche of an artist who, almost like a modern Icarus, burned himself at the blaze of his own disarming genius.

Ian's life, a true modern Greek drama, was divided between his wife Deborah, whom he married very young and with whom he had a daughter, and his lover, a Belgian journalist named Annik Honoré, whom Ian met backstage at one of his concerts. This duality, this split between the domestic hearth and the fatal attraction to an accomplice in his artistic journey, is one of the film's main pillars, an element that increases the tragic dimension and empathy for a man torn apart by forces too great for him, trapped between duties and irrepressible desires. The fidelity to the biography, based largely on Deborah Curtis's book, Touching From a Distance, lends the narrative a startling depth and veracity, avoiding any hagiographic sugarcoating.

There is no emphasis or panegyric rhetoric in the film, which owes its title to a song Ian wrote, with prescient melancholy, in memory of a friend killed by epilepsy: "She’s Lost Control." The title itself, in its dual meaning, becomes a poignant metaphor not only for the pathology, but also for the protagonist's loss of all mastery over his own life, his own body, his own destiny.

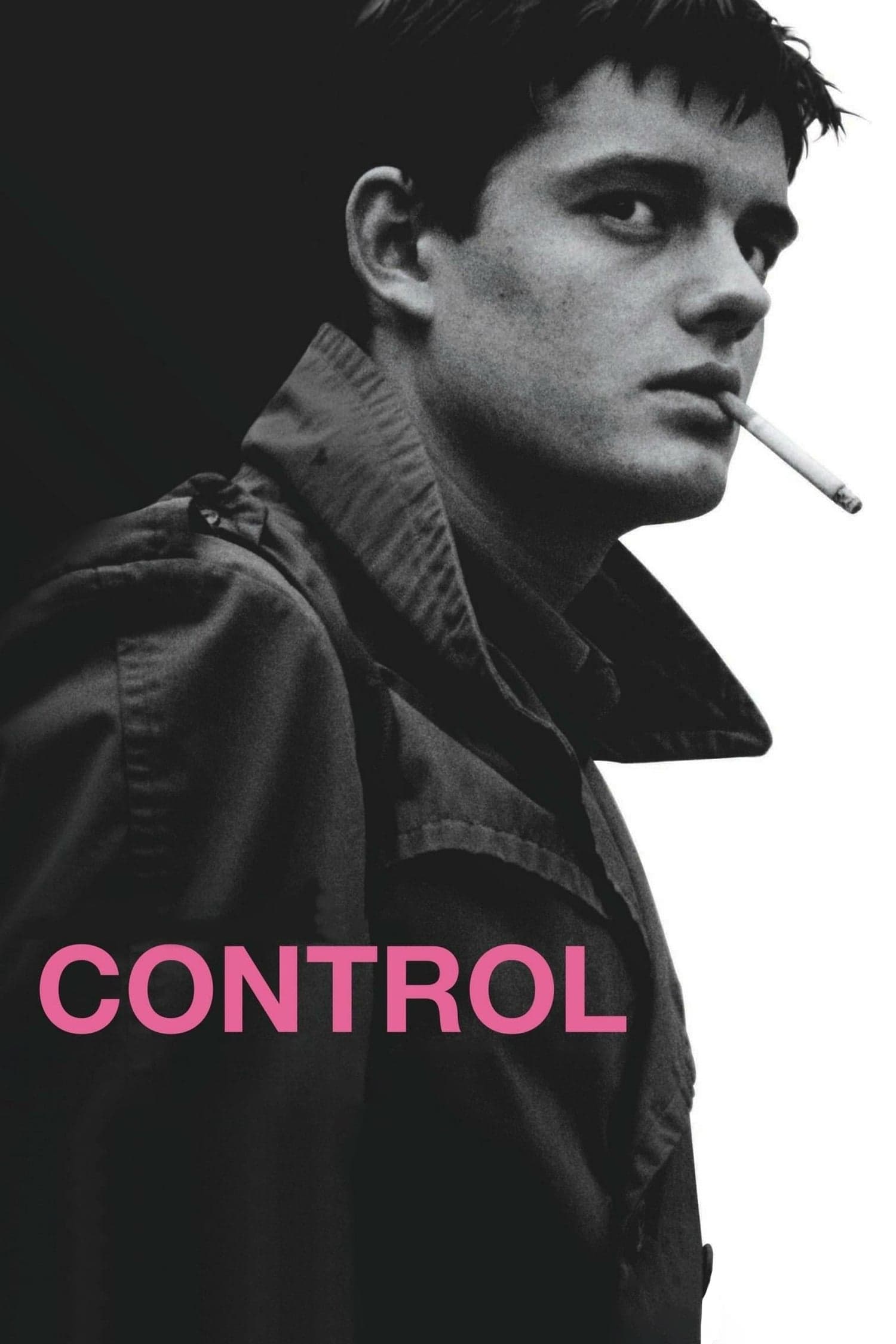

Corbijn films in a black and white of dazzling intensity that is not a mere stylistic choice, but true narrative material. This monochromatism reverberates the band's mood and its genesis in a post-industrial, peripheral, marginal England. The spirit of a cold and raw Manchester, yet vibrant with a nihilistic but vital creativity, returns in the work as a pivotal iconographic element, almost a silent character that defines spaces and moods. It is not a merely aestheticizing black and white, but a formal reinterpretation that evokes neorealism for its ability to capture the desolation of environments and the gravity of faces, while maintaining a sophisticated composition reminiscent of great art photography.

It must be said that Corbijn, here in his directorial debut, is a photographer turned filmmaker, but with a visual experience and sensibility forged by decades of work. Famous for his seductive and aestheticizing black and white photographs, capable of capturing the soul of subjects with a skillful play of light and shadow, this was the framework with which Corbijn portrayed a pantheon of international rock stars: from Mick Jagger to Nick Cave, from Tom Waits to Johnny Rotten. His cinematography for Control is a natural extension of his stylistic signature, where every shot is meditated, every detail significant, transforming sparse environments and raw performances into vivid compositions, imbued with palpable melancholy and austere beauty. This almost documentary approach, yet imbued with a profound sensitivity to image, is what elevates the film beyond a simple biopic.

Control is a film destabilizing in some ways, because it is filmed with the semantic power of a documentary, its almost clinical fidelity to facts and characters, but also with the narrative force of dramatization of events. This hybridization makes it a unique work in the landscape of musical biographies. Sam Riley's interpretation of Ian Curtis is a true tour de force: he does not limit himself to a mere physical or vocal imitation, but embodies the musician's tormented soul with a disarming mimesis, capable of conveying his neuroses, epiphanies, and falls. The stage performances, reproduced with almost maniacal fidelity, are the film's pulsating and feverish heart, restoring Curtis's convulsive and hypnotic physicality.

The result is an enchanting work, in its intrinsically tragic nature, which, through the emotional devastation of a young man, opens the doors to his lucid introspective analysis, highlighting, with a moving yet brutal delicacy, his striking genius and tremendous fragility. Control does not glorify suffering, but explores it with respect and acumen, leaving the viewer with an awareness of the complexity of an existence that, though brief, left an indelible mark on the history of music and, ultimately, art.

Main Actors

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...