Crip Camp

2020

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(2 votes)

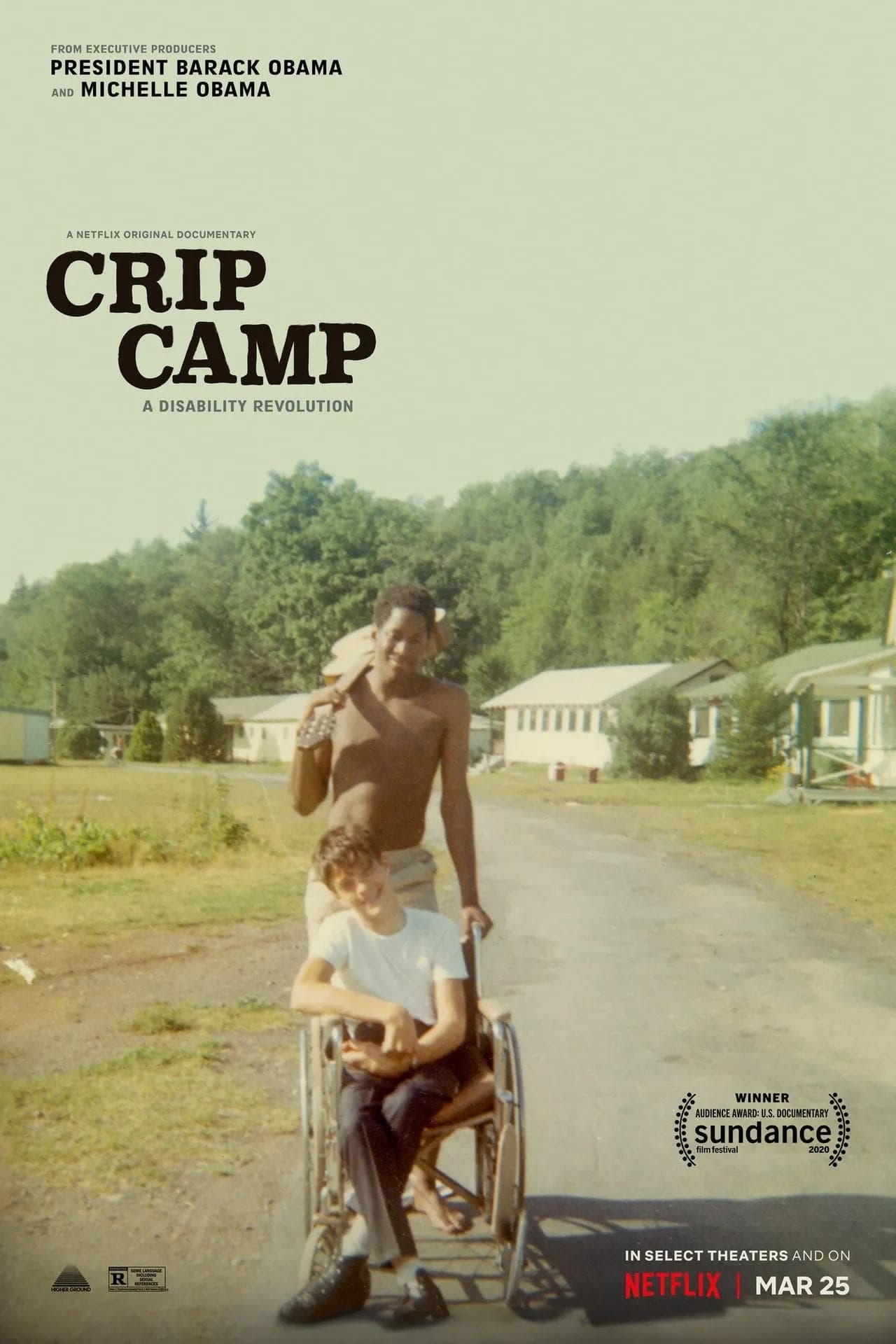

Directors

Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution (2020) by Nicole Newnham and James LeBrecht, is not simply a documentary. It is an act of historical reclamation, a political manifesto of rare power, and, above all, a subversive and joyful narrative that dismantles decades of pietistic representations of disability. The film, produced by the Obamas' Higher Ground, does not ask for compassion, but demands attention. It does not show victims, but reveals revolutionaries. It is a sharp work that uses archival footage to rewrite the present, demonstrating how the struggle for the most basic civil rights often stems from an unexpected utopia.

The film opens in a place that seems straight out of a libertarian dream: Camp Jened, a summer camp for disabled teenagers run by hippies in the early 1970s. This is not a medical institution, but a laboratory of humanity. In this open space, disability is the norm, not the exception. For the first time, teenagers with polio, cerebral palsy, or spina bifida cease to be the object of care or others' commiseration to become simply... teenagers. They discuss sex, smoke weed, play music, argue, and fall in love with a freedom that the outside world, an America of architectural and mental barriers, fiercely denies them.

The intellectual implication of this first part is seismic. Camp Jened effects a fundamental transformation of consciousness: it shifts the "problem" from the individual to society. The campers stop asking "What's wrong with me?" and start asking "What's wrong with a world that doesn't account for me?". This paradigm shift is the seed of the revolution. The camp becomes a political forge where a collective identity is forged, a "crip consciousness" that understands isolation is a strategy of control and that the only possible response is collective action. The second half of the film follows the protagonists of that idyllic summer into the real world, where utopia clashes with the rubber wall of bureaucracy and prejudice. The relationship with the outside world is one of pure conflict. The narrative focuses on the charismatic figure of Judy Heumann and the fight for the implementation of Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, a fundamental law that prohibited discrimination based on disability in federal programs.

When the Carter administration delayed its implementation, Jened veterans organized a historic protest action: the "504 Sit-in" of 1977 in San Francisco, the longest occupation of a federal building in United States history. Here, the film becomes a breathtaking political thriller. We see the disabled community, with all its physical fragility and unwavering political strength, organize a 28-day resistance. In a shrewd and powerful testament to solidarity among the oppressed, they receive crucial support from other civil rights groups, such as the Black Panthers, who brought them hot food daily, recognizing their struggle as part of the same battle for dignity. Disability ceases to be a medical issue and unequivocally becomes a civil rights issue.

Cinema, by its visual nature, tends to observe disability from the outside, objectifying it. Literature, by contrast, has often had the tools to inhabit disability from within. While Herman Melville's Captain Ahab in Moby Dick can be read as the prototype of the villain whose disability fuels a destructive monomania ("All my means are sane, my motive and my object mad"), Benjy Compson's interior monologue in William Faulkner's The Sound and the Fury is a revolutionary attempt to represent a non-neurotypical consciousness unfiltered, from within its fragmented perception. Literature can explore subjectivity; mainstream cinema too often stops at the surface. Crip Camp manages to achieve a miracle: despite being a film, it reaches the interior depth of literature. It does so by using the most honest language possible: archival footage filmed by the community itself and the first-person narration of those who were there. It categorically rejects the pathetic to embrace the political. It does not show us "what it feels like to be disabled," but "what disabled people did to change the world."

Crip Camp leaves us with a truth as simple as it is powerful: rights are never granted. They are conquered.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...