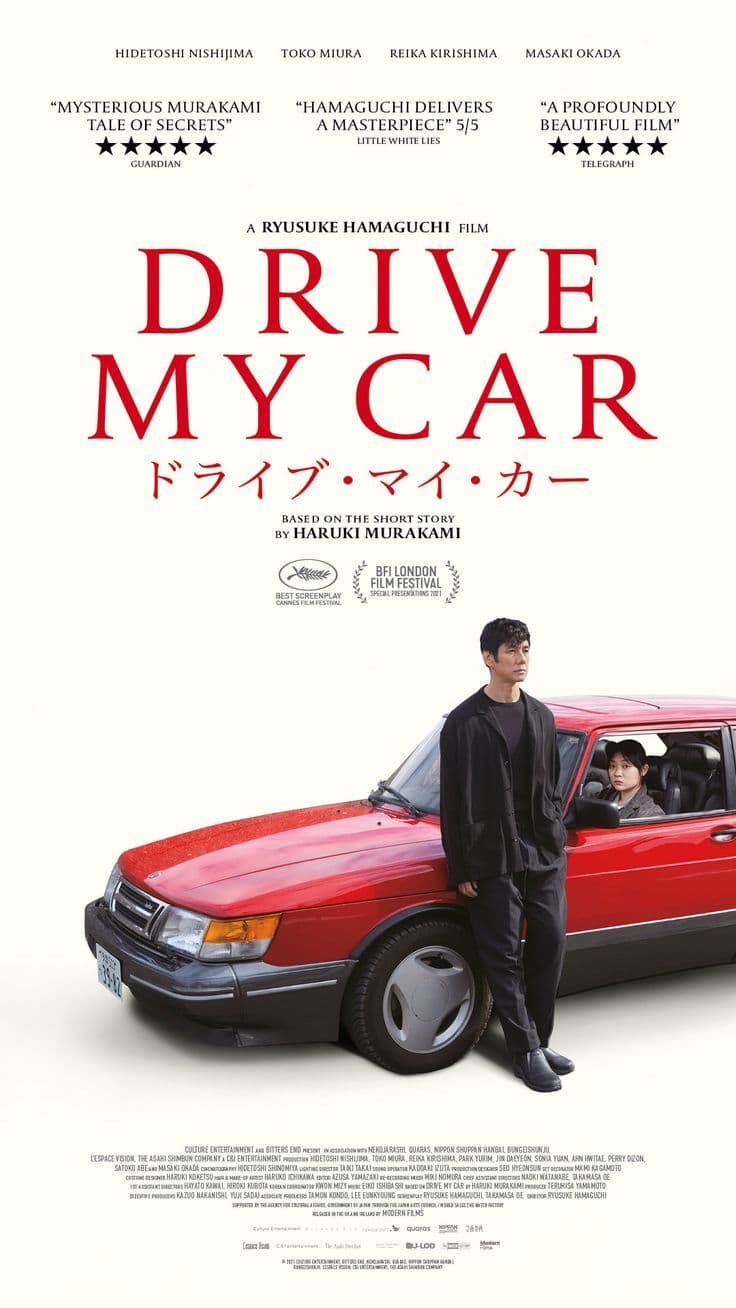

Drive My Car

2021

Rate this movie

Average: 4.25 / 5

(4 votes)

Director

Drive My Car is a three-hour monumental work that rejects every emotional shortcut to embark on a phenomenological dissection of pain, language, and silence. Far from being a conventional drama, the film takes shape as a philosophical treatise disguised as a road movie, a ruthless investigation into incommunicability that finds unexpected catharsis in the therapeutic power of theatrical text. It is cinema that demands unconditional surrender, but which repays with an almost unbearable intellectual and emotional depth. Hamaguchi's characters, borrowed from Haruki Murakami's laconic prose, are essentially Leibnizian monads: entities closed in on themselves, "windowless," containing a universe of private pain inaccessible from the outside. Yūsuke Kafuku, the protagonist, and his wife Oto built a union based on a ritual—sex, followed by post-coital storytelling—that masks an abyssal chasm of silence regarding the foundational tragedy of their lives: the death of a daughter. Their communication is a code, not a dialogue, a way to orbit around pain without ever naming it.

When Oto dies suddenly, Yūsuke remains imprisoned in his monad, continuing to dialogue with a ghost through the tapes she recorded for him. The same applies to his young and taciturn driver, Misaki, and to the young actor Takatsuki, both custodians of unexpressed traumas. In this exploration of alienation, Hamaguchi positions himself as the direct heir to the great European masters of incommunicability. One senses the echo of Michelangelo Antonioni in the composition of spaces, where the desolation of the landscape (highways, winter Hiroshima) becomes a projection of the characters' inner emptiness. And one feels the proximity to Ingmar Bergman, especially in the way the film focuses on faces as maps of psychological torment that words cannot contain.

If, as Ludwig Wittgenstein stated in his Tractatus, "the limits of my language mean the limits of my world," then the characters in Drive My Car are trapped in an asphyxiating world. Their inability to articulate pain condemns them to an existential stasis. How can windowless monads communicate? Hamaguchi offers an answer as brilliant as it is ancient: through the Logos. In this film, the Logos—the Word, Reason, structured Speech—is the text of Anton Chekhov, Uncle Vanya. Yūsuke, as a director, does not merely stage a play, but orchestrates a therapeutic process. He obliges his actors, from different languages and cultures (Japanese, Korean, Mandarin, sign language), to perform a text that is not their own, in a language that often is not theirs. By repeating Chekhov's words, the characters find a vehicle to express feelings they would not be able to formulate with their own language. Vanya's pain becomes Yūsuke's pain. The actor playing Vanya, Takatsuki, by confronting an external text, is forced to confront his own inner chaos. Chekhov's Logos becomes an external structure that allows the inexpressible to be given form.

The multilingual play demonstrates that true communication does not reside in the literal meaning of words, but in intention, rhythm, breath, gaze. It is a profoundly Wittgensteinian insight: meaning lies in use, in context, in the shared language-game, even when the languages are different. The final catharsis, in fact, does not occur through a direct and spontaneous confession between Yūsuke and Misaki in their own language, but through two mediated acts: Yūsuke's theatrical performance as he finally takes on the role of Vanya, and Misaki's confession in her desolate childhood home in Hokkaido, a place that is itself a "text" of her suffering.

Ryusuke Hamaguchi is a leading figure in a new Japanese cinema that, while dialoguing with its masters, has found an autonomous voice. His approach distinctly differs from that of other greats of the past and present. Compared to Hirokazu Kore-eda, Hamaguchi shares a certain humanism and attention to interpersonal dynamics, but is formally more rigorous, colder, and less inclined to consolatory sentimentality. Where Kore-eda seeks warmth in dysfunctional families, Hamaguchi explores their icy distance. The contrast with Takeshi Kitano is even more evident. Kitano's minimalism is made of explosive silences and sudden, stylized violence. Hamaguchi's minimalism, however, is verbose, built on very long dialogues and a purely psychological tension.

Hamaguchi's cinema, along with that of other authors like Kōji Fukada, represents a trend toward long-duration, almost literary works that prioritize the complexity of the word and the patient observation of human relationships, moving away from the genres (J-horror, yakuza movie) that had characterized Japanese cinematic exports in previous decades.

Drive My Car is a film that was missing, it is a work that theorizes itself as it unfolds, using the act of theatrical performance as a metaphor for life and as a tool for healing. The old red Saab 900 is not just a car, but a liminal space: a mobile confessional, a sanctuary, and a traveling stage where two entities, Yūsuke and Misaki, through shared silence and the Logos of others, finally find a way to open a crack in the wall of their solitude and let a fragile ray of light enter. And it is precisely there that the director awaits us.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Memorable Scene

Comments

Loading comments...