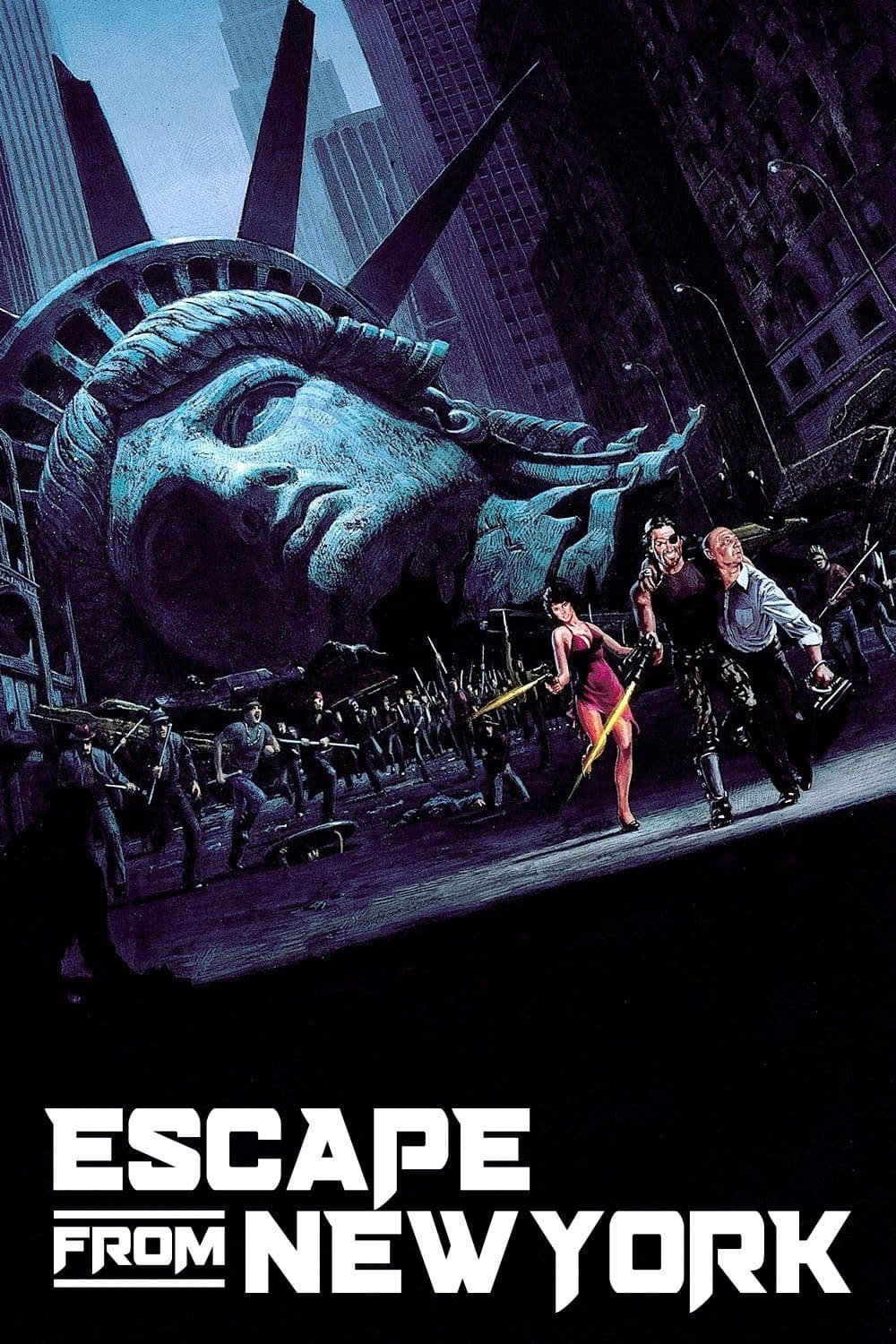

Escape from New York

1981

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

In 1972, John Carpenter wrote a story treatment set in a dystopian future but found no production company willing to believe in the project: too strange, too violent, too politically incorrect. It was an anticipating, almost prescient vision of an America afflicted by deep mistrust in institutions, still shaken by the trauma of Vietnam, and about to face the Watergate scandal. Such an openly cynical and disillusioned narrative about urban destiny and the fallibility of central government was perhaps too bitter for an audience that, though in transition, had not yet fully processed the sense of social and moral decay that would characterize the subsequent years. The film's punk and nihilistic sensibility was, in short, ahead of its time.

Nine years later, bolstered by the success of Halloween (1978), which had demonstrated his mastery in generating suspense and box office returns with limited budgets, Carpenter received an offer to make the film from the production company AVCO Embassy Pictures, which provided him with six million dollars. This was a meager sum even for that era, but far from being a limitation, it transformed into a catalyst for the director's ingenuity, forcing him into ingenious visual solutions – from detailed models for aerial views of Manhattan to real exterior night shots, such as the dilapidated ruins of Union Station in St. Louis, Missouri, which magnificently evoked a New York fallen into ruin.

Carpenter sets his film in a futuristic New York transformed into an open-air prison. The temporal setting is 1997, a near-future where the dizzying rise in the crime rate has forced the government to turn the island of Manhattan into a colossal detention center. This premise, at the time, was not just entertainment science fiction but a dystopia rooted in the growing urban anxieties of the era: the perception of an escalation of violence, the decline of city centers, the failure of rehabilitation systems. The idea of transforming Manhattan into a gigantic social waste bin, where problems were simply confined and forgotten, was a crude metaphor for the contempt for marginalized classes and an indictment of policies of mere containment.

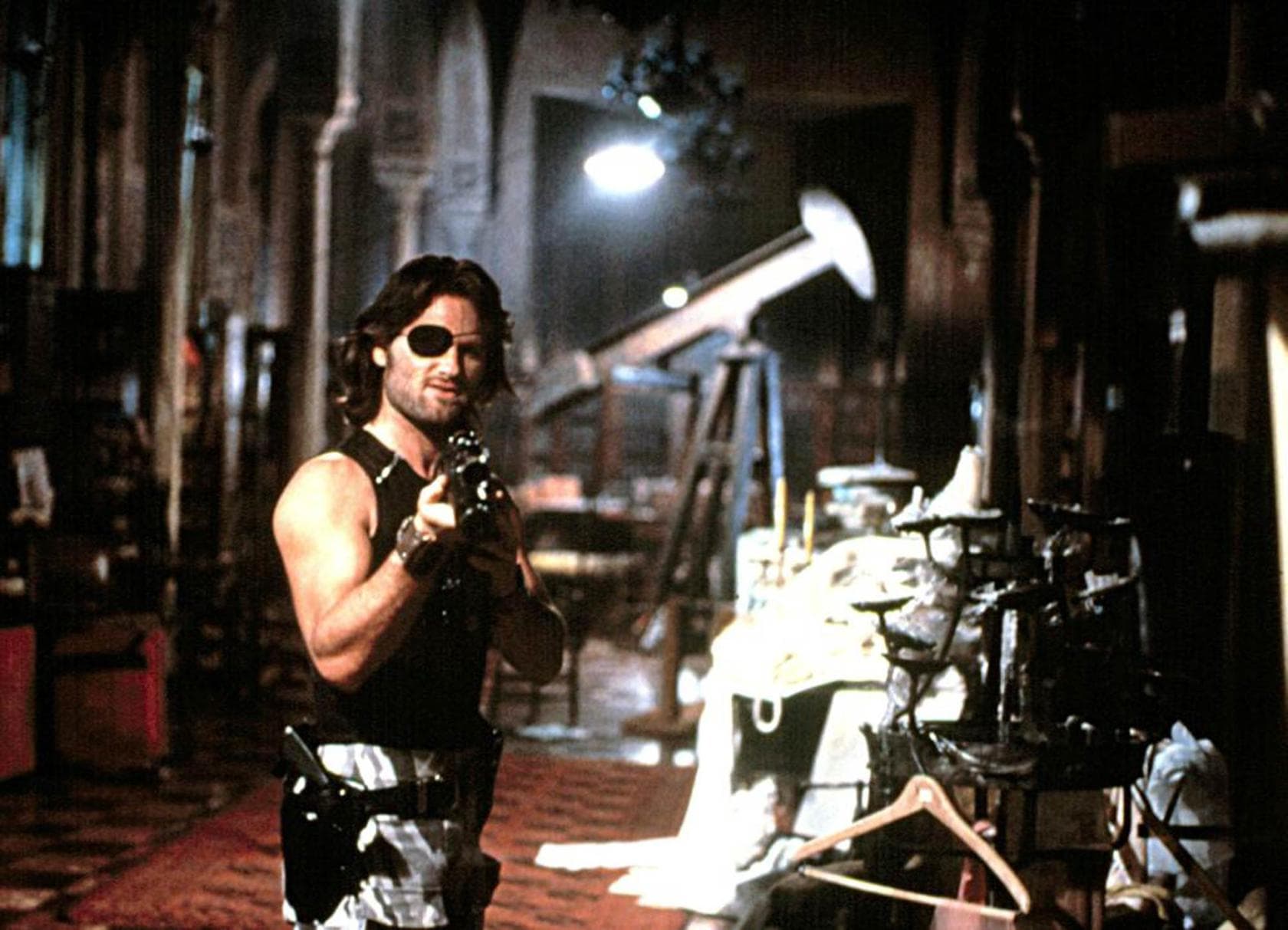

In this ghetto-metropolis roams the worst dregs of the globe, tyrannized by the Duke, leader of this criminal microcosm, portrayed with theatrical cruelty by Isaac Hayes. His figure is a magnificent counterpoint to the anti-hero par excellence that the film presents to us. When the presidential plane crashes due to a malfunction and the US President (a hypocritical and cowardly Donald Pleasence) falls into the Duke's hands, it will be Snake Plissken who must extricate the institutions from their predicament. Kurt Russell, in the role of Snake Plissken, forges an icon destined to last: a cynical and disillusioned war veteran, a decorated war criminal who is the exact antithesis of the polished action hero, closer to a Clint Eastwood from The Good, the Bad and the Ugly dropped into an urban hell. His eye patch, shuffling gait, and hoarse voice, along with a perpetual sarcasm, make him an archetype of individualistic rebellion against a corrupt system that deserves no loyalty.

He will be sent into Dante's Malebolge to retrieve the precious hostage, with a timed device injected into his veins, set to explode when his allotted time runs out. This narrative device is not just a brilliant engine for tension but a symbol of the total depersonalization and coercion exerted by power: Plissken is reduced to a mere instrument, his very life a negotiable currency. It is a dark and well-scripted film, with a relentless narrative pace and a mythological protagonist. Its darkness is not only aesthetic but thematic: the film paints a bleak picture of human nature and power, suggesting that, beyond political rhetoric, violence and oppression are the true driving forces.

The music, created by Carpenter himself in collaboration with Alan Howarth, is distressing and oppressive, entirely functional to the narrative. The director's trademark, made of pulsating synthesizers, atmospheric drones, and minimalist yet incisive melodies, creates a soundscape that is almost a character in itself. The dark and repetitive themes amplify the sense of impending threat and despair, transforming the sequences into an almost sensorial experience, where sound is as crucial as the image in building Manhattan's claustrophobia. The influence of these scores is today recognizable in countless genre soundtracks, demonstrating their originality and power.

The use of light in this film is interesting, a spectrum of dark shades covering every tone of black: from the hazy and flickering exteriors (perpetually nocturnal, highlighting an endless night of lost hope) to the gothic and uncertain interiors, where men seek refuge from the fury of events. Carpenter, a master in the art of creating atmospheres with limited resources, maximizes the contrast between flickering neon lights and deep shadows, lending the film an almost painterly dimension, a dystopian neo-noir that evokes a sense of isolation and desolation. Dean Cundey's cinematography does not just light the scene but shapes it, making New York itself a sprawling and menacing creature. The film is not just an action film but a work deeply rooted in the anxieties of its time, a social dystopia that still resonates today for its brutal honesty and its iconoclastic rebellious spirit.

Main Actors

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...