Fantasia

1940

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Directors

Fantasia is a pioneering work that revolutionized the way animated cinema was conceived, an audacious fusion of classical music and visual art that has enchanted generations of viewers. It is not a mere cartoon, but a true "visual concert," an ambition Walt Disney had long harbored, desiring to elevate animation to a complete art form, capable of conversing with the noblest expressions of culture. An almost mad project for its time, which defied not only narrative conventions but also market logic, presenting itself as an immersive and transcendent experience.

Walt Disney, with this ambitious project, created a unique synesthetic experience, where images take shape and come alive to the rhythm of the greatest musical compositions, from Bach to Beethoven, from Stravinsky to Tchaikovsky. The intuition was to allow music to dictate the rhythm and form of the images, not vice versa. To realize this vision, Disney availed himself of the collaboration of the renowned conductor Leopold Stokowski, whose presence was not just technical but also scenic, acting as a bridge between the audience and the orchestra, as a guide through the labyrinth of sensations that the film offers. This partnership infused the work with a gravitas and authenticity that went far beyond mere entertainment.

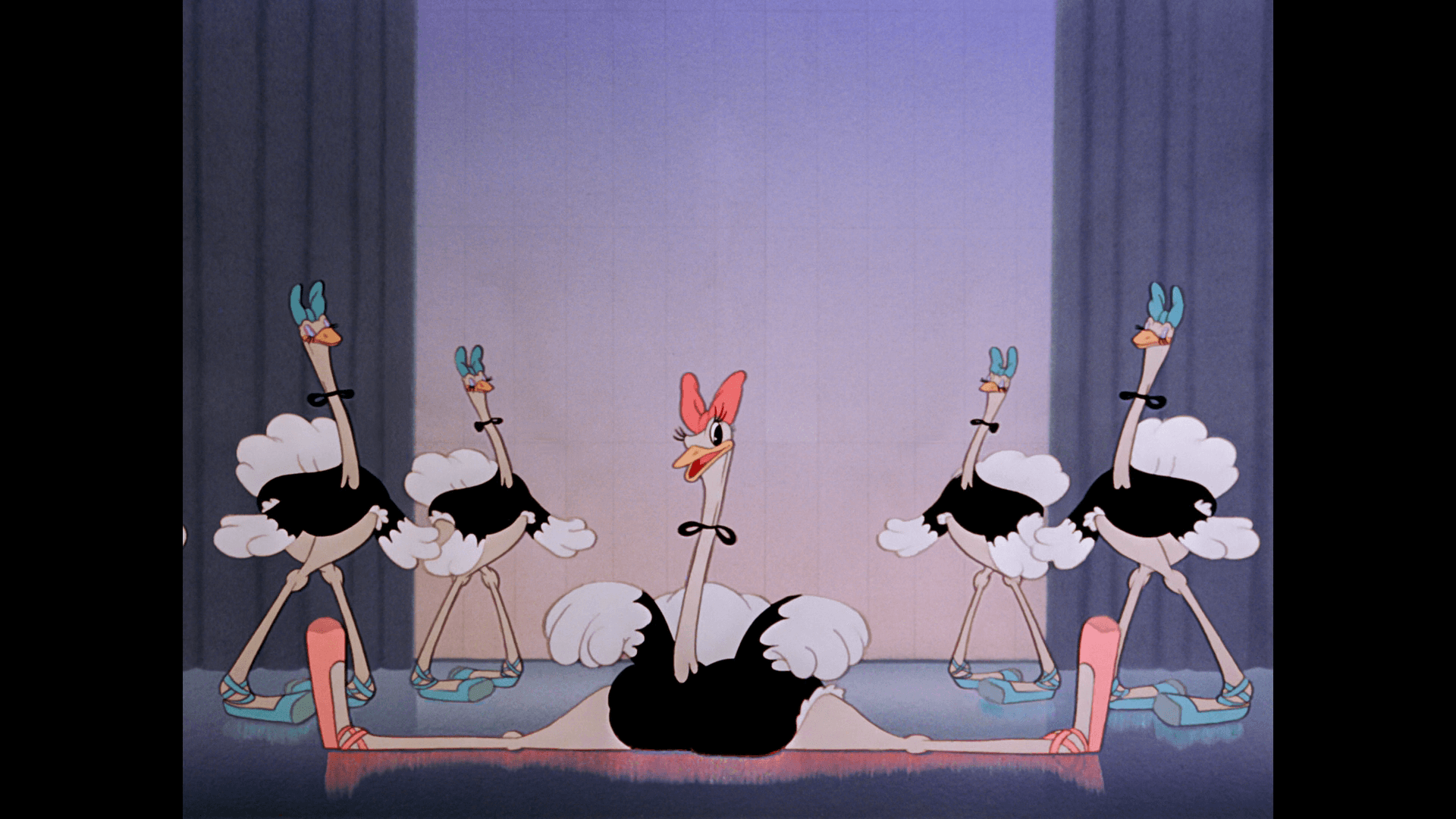

The film is an extraordinary journey through fantastic and surreal worlds, where dinosaurs dance to the rhythm of "The Rite of Spring," hippopotamuses twirl to the notes of "Dance of the Hours," and fairies and sprites float through the air to the sound of "The Nutcracker Suite." Each segment is a microcosm unto itself, a narrative and aesthetic universe that, while deriving from the same musical matrix, explores radically different themes and visual styles. The "Rite of Spring" sequence, for example, is not just a chronicle of biological evolution, but a powerful and visceral meditation on the primordial force of nature, on the struggle for survival and the inexorable cycle of life and death, an interpretation that Stravinsky himself, despite reservations about artistic license, recognized as possessing its own intrinsic validity.

Fantasia is a work that challenged the boundaries of animation, experimenting with new techniques and visual languages, and paving the way for a new way of conceiving the relationship between music and image. One can trace echoes of the visual experimentations of the European avant-garde, from the abstract films of Oskar Fischinger and Len Lye, who already in the 1920s and 30s explored the visualization of sound, to the idea of the Wagnerian "Gesamtkunstwerk," the total work of art. Disney elevates this concept, bringing it to the screen with a scale and complexity never before seen.

Disney unleashed the creative flair of his animators and produced a work where note and drawing form an indissoluble vector. These are not mere illustrations of music, but true visual exegeses that emerge from the very fabric of the score. From Tchaikovsky to Ponchielli, from Mussorgsky to Bach, all the greatest orchestral Suites are iconographically rewritten by Walt Disney's pencil, transformed into a visual palimpsest that reveals new nuances and interpretations of the pieces.

The final result is a work of the highest artistic quality, where the drawings are the soul's dreamlike motion, wistfully embroidering upon tonal scales, almost like closing one's eyes to the notes of a great symphony and reliving its musical echoes in a dream through dazzling apparitions. It is an experience that transcends simple viewing, inviting the viewer into an almost synesthetic immersion, where the boundaries between auditory and visual perception become blurred. Bach's "Toccata and Fugue in D Minor," for example, is pure visual abstraction, a ballet of lines and colors that float and intersect, almost as if to visualize the movement of sound waves, anticipating by decades the aesthetics of music videos and multimedia art installations.

The film, devoid of a traditional plot, is structured as a series of animated segments, each inspired by a different classical music piece. This unconventional choice distances it from classical narrative, propelling it towards a more contemplative and experiential cinema. These segments, while independent, are united by a common thread: the celebration of music, fantasy, and art. The presentation of the pieces by music critic Deems Taylor, serving as narrator and unifying element, helps create a sense of cohesion and introduces the audience, even those less accustomed to classical music, to the context and intentions of each piece.

The drawings and story arise from the suggestion of the music flowing in the background, seeming to spring directly from the musical score. Through animation, Disney brings to life visual interpretations of great musical compositions, creating a dialogue between sound and image that stimulates the viewer's imagination and emotions in a profoundly original and lasting way. It is a lesson in how artistic perception can be shaped and enriched by a media fusion.

The harmony and taste with which drawings and music are combined and fused are admirable, almost a sonic fresco that indelibly imprints itself on the imagination of those who approach it. A special mention for the technique in which film footage and animation are superimposed: the Compositing technique. It is the first film to use this technique, later widely adopted in Mary Poppins and other Disney works. But the innovation doesn't stop there: Fantasia was the first film to be projected with the "Fantasound" audio system, a precursor to modern stereophonic and surround sound, with an orchestra recorded with 33 microphones and reproduced through multiple loudspeakers. Although for practical reasons and high costs Fantasound did not achieve widespread diffusion, it represented an epochal leap in cinematic sound technology.

In particular, Disney used a variant of compositing called "optical printing." This process involved superimposing different visual elements (animated drawings, painted backgrounds, live-action actors) onto a single film strip, through a series of optical exposures and mattes. This technical complexity was necessary to achieve the depth and visual richness that distinguished Fantasia, allowing for effects like transparency, fog, and the superimposition of animation layers, lending the images an almost three-dimensional quality.

In conclusion, Fantasia was a landmark work, a film that profoundly influenced animated cinema and popular culture. Its fusion of music and image, its experimentation with new techniques, and its celebration of fantasy have inspired generations of artists. Despite initial financial difficulties, exacerbated by World War II which limited its international distribution, Fantasia was rediscovered and re-evaluated over time, especially in the 1960s and 70s, when its visionary and psychedelic spirit found a receptive audience.

There are countless memorable scenes, and perhaps one above all others: the hippopotamus ballerina performing Amilcare Ponchielli's "Dance of the Hours," dispensing overflowing grace in her graceful movements, almost liberated from gravity. That segment, with its subtle humor and technical mastery, perfectly embodies the spirit of Fantasia: the ability to take the most highbrow classical music and make it accessible, entertaining, and profoundly human, without ever descending into banality, but rather elevating it to a proscenium of pure joy and wonder.

Main Actors

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...