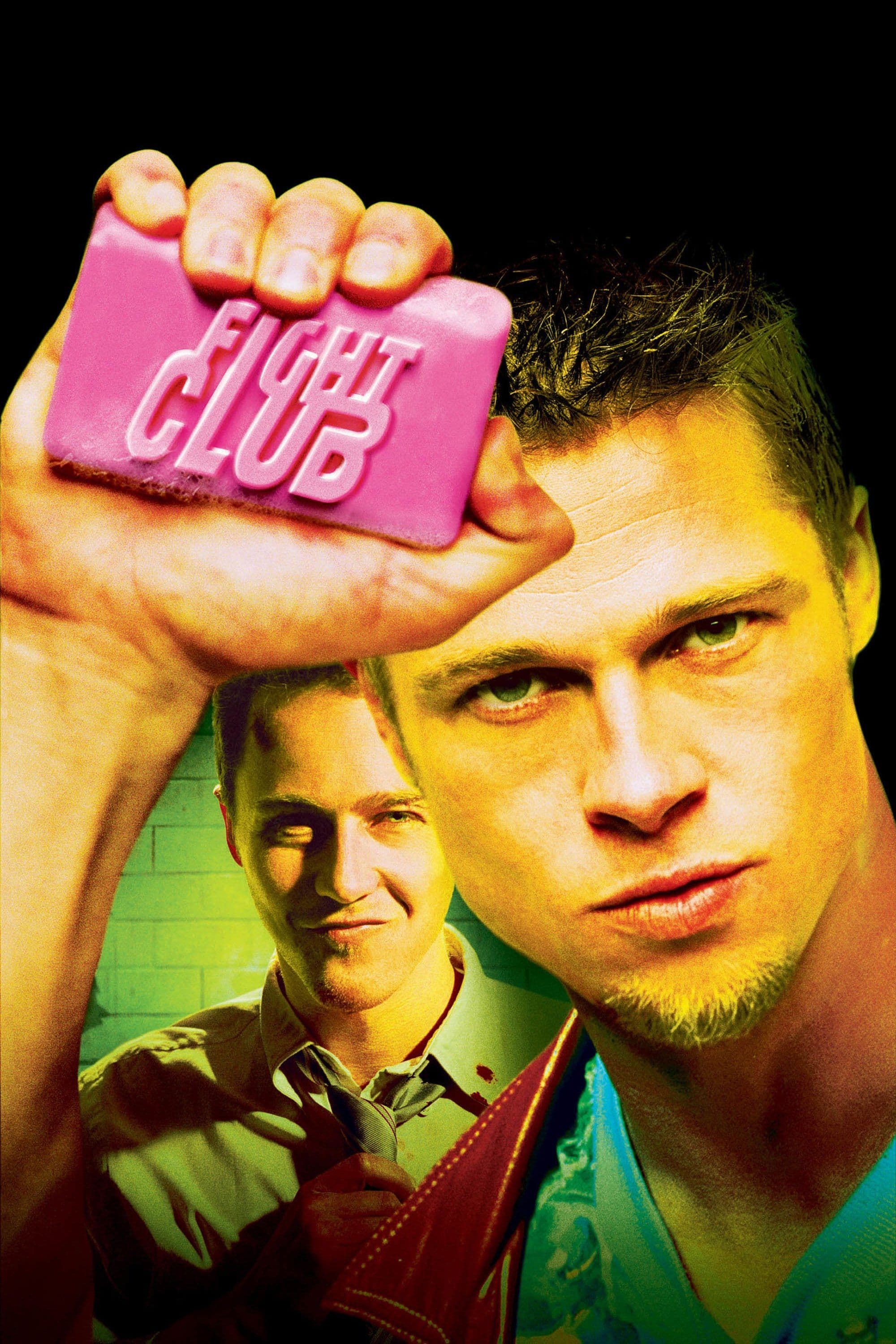

Fight Club

1999

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

There is a voice within each of us, a hidden part of ourselves that continues, gnashing its teeth and whispering in the shadows, to comment on our actions, to furtively speak to us, inspiring us to other actions. It is the echo of a primordial self, a Jungian shadow stirring in the recesses of the psyche, or the manifestation of the Freudian Id, longing to subvert the order imposed by civilization, an archetypal force that challenges conventions and the veneer of civilization.

Chuck Palahniuk, a writer who explores the psychological register of every story he writes with disarming rawness and lucidity, is interested in understanding what this voice is, to make it a powerful narrative element around which to build a story. His prose, razor-sharp and often disturbing, lends itself to investigating the latent pathologies of contemporary society, the fetishes of consumerism, and the resulting identity crisis, transforming individual malaise into a collective cry.

The grand narrative device of Fight Club, his first novel published in 1996, is centered on this presence that splits each of us into an “other self,” like a reflection reverberated in daily life that comes to life, a guardian angel fabricated within the folds of our consciousness. It is a narrative that borders on an inverse bildungsroman, where growth is not towards integration, but towards radical fragmentation, a nihilistic journey into the abyss of the psyche.

Fight Club is not an easy story to transpose to the big screen; it contains psychological implications difficult to render visually and a plot that is certainly politically incorrect in its direct assault on the pulsating heart of capitalism and toxic masculinity. Yet Fincher delivers a sumptuous film where everything appears perfectly synchronized and subservient to the narrative mechanism. Fincher's direction does not merely illustrate the story; it elevates it, dissects it, and reassembles it with a mastery that makes it a work of art in itself. His stylistic signature – the somber aesthetic, Jeff Cronenweth's obsessively clean cinematography, the neurotic editing that sometimes inserts subliminal frames of Tyler Durden before his revelation – transforms the novel's disquiet into a visceral and disturbing experience. The sound, meticulously crafted, with the industrial soundtrack by the Dust Brothers, becomes an additional character, a rhythmic pulse that amplifies alienation and cathartic violence.

The protagonist (whose name is never revealed, emphasizing his anonymous interchangeability within the system that swallows him) works for an automobile company, in the insurance branch. He is a cog in a system that guarantees financial stability at the expense of the soul.

He is neurotic, enslaved by the objects he buys with manic seriality, obsessed with Ikea furniture and a catalog of prefabricated life, paranoid and frustrated by a life spent in solitude, a regular attendee of support groups for the most disparate illnesses to indulge a morbid voyeurism and to cry in a group, pursuing a sort of cathartic therapy. His search for an authentic emotion, even a pain not his own, in a world anesthetized by consumption, is a symptom of his profound anomie, an existential pathology masked as office neurosis.

During one of his business trips, he meets the man who will change his life: Tyler Durden. A modern Mephistopheles, a demiurge of chaos who bursts into his aseptic existence.

He presents himself as a soap salesman; he seems like a bizarre, slightly unhinged guy, but his nonchalance, his animal charm, and his radical estrangement from the rules of the bourgeois world make him irresistible to a man who has lost all sense of self.

Returning home, the narrator discovers that his home has been destroyed by a gas leak; desperate, he calls Durden, who offers to host him in his dilapidated dwelling. An invitation to descend into the underworld, to strip away all material comforts to embrace the brutal authenticity of the street.

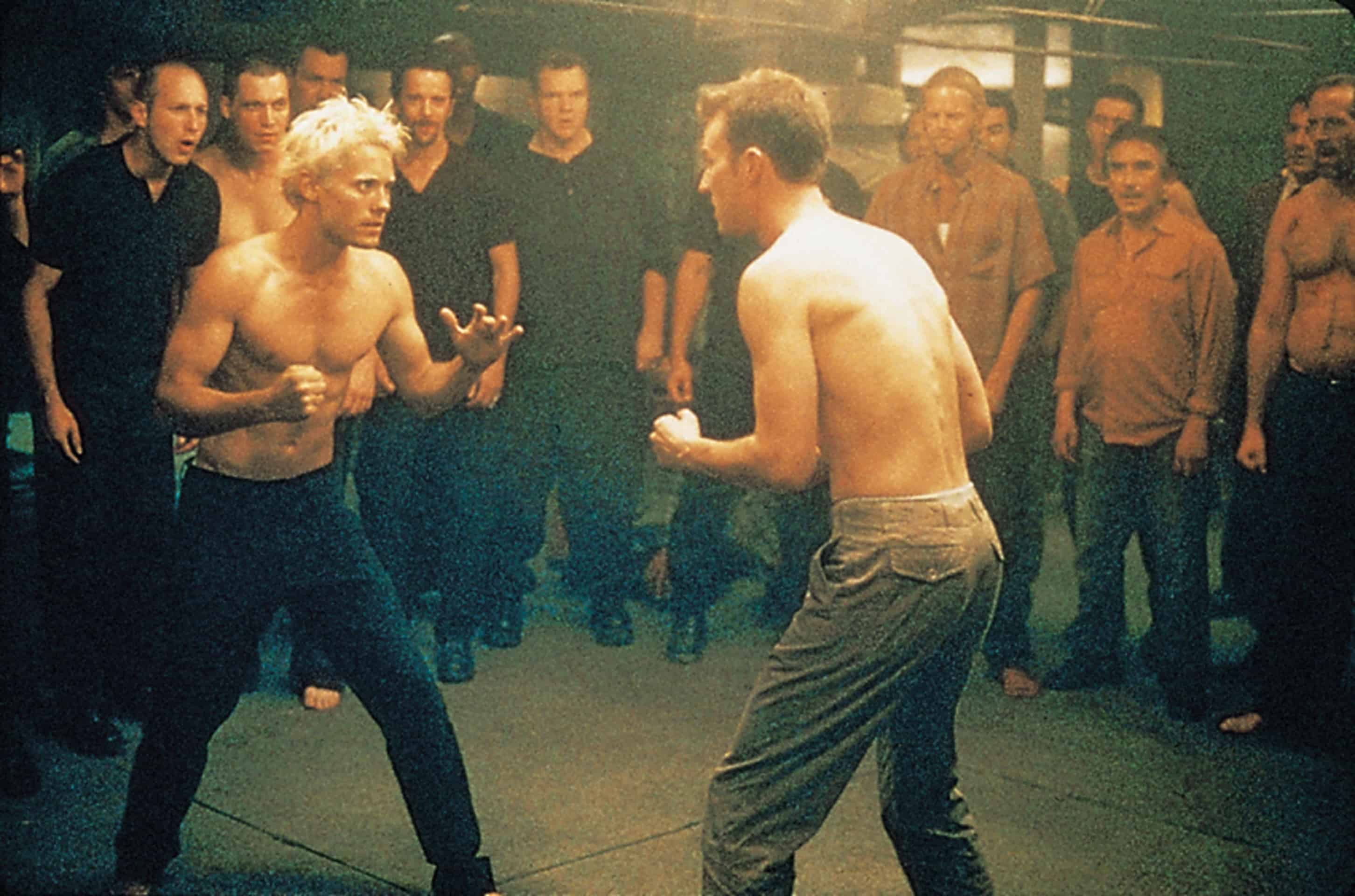

By spending time with Durden, the narrator adopts his habits as a frequenter of the metropolitan night, learning to fight as a therapy to heal his spirit. Violence is not an end in itself, but an initiatory ritual, a way to rediscover one's body, one's pain, one's true essence outside the golden cages of consumerism.

Thus begins the creation of a club where members from all walks of life beat each other senseless, purely for the sake of venting, without any competitive purpose. It is a club of liberation, a primordial rite for men castrated by modern society, a visceral reaction to the crisis of contemporary masculinity. Here, the body reasserts itself as the last bastion of existence, physical pain as the last, authentic sensation in an otherwise muffled existence.

Over time, what seemed like an underground sect of eccentrics will transform into a paramilitary organization with subversive aims. Project Mayhem is no longer just therapy, but an anarchist manifesto, a crusade against the foundations of the capitalist system, against banks and credit cards that cage man in a spiral of debt and false well-being. This progression from the personal to the political, from individual catharsis to social subversion, is one of the film's most fascinating and controversial aspects, which many have misunderstood as an apology for violence, when in reality it is a biting satire on the despair of a generation.

Once Durden's true intentions are understood, the narrator desperately tries to appeal to him not to commit attacks, but the question he poses to Durden echoes in a large empty room, a pale reflection from a mirror showing him his bewildered face. The unreliable narrator mechanism, a literary topos masterfully rendered cinematically here, reveals itself in all its power. The discovery is not just a plot revelation, but a profound inquiry into identity, the fragmentation of the psyche, and the internal struggle between the desire for conformity and the impulse for destruction. The climax is not external, but an epic battle between the two halves of a single individual, a Shakespearean conflict that unfolds in the heart of the urban night.

Nothing is as it seems; it never really is. And precisely this ambiguity, this constant questioning of perception and reality, has made Fight Club a generational cult, a film that continues to provoke, fascinate, and generate debate, decades after its controversial release in cinemas, remaining a perfect seismograph of 21st-century neuroses.

Genres

Countries

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...