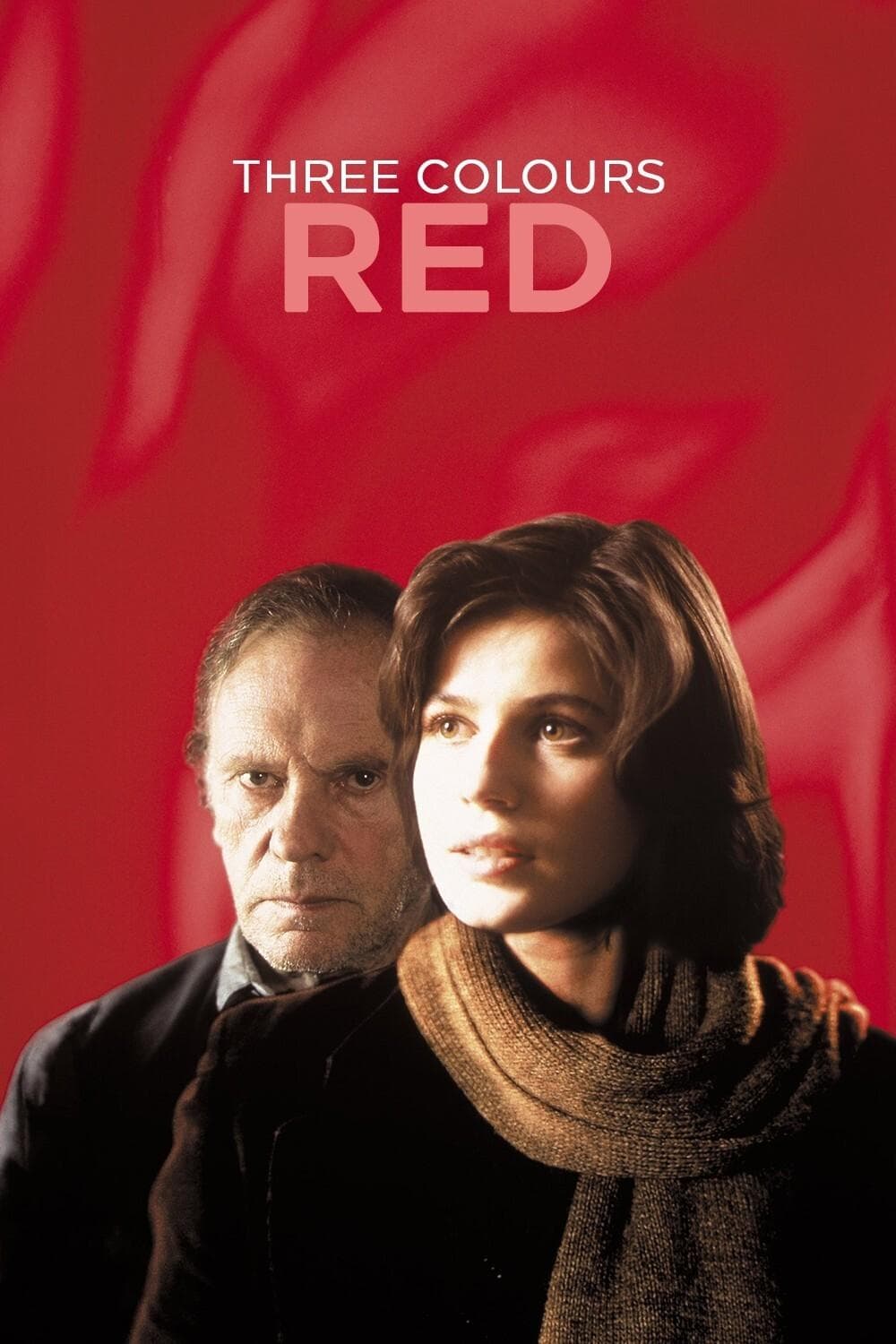

Three Colors: Red

1994

Rate this movie

Average: 4.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

Krzysztof Kieslowski is a director who left this earth too soon, unable to grace us with more films like this small, luminous masterpiece. His sudden passing, which occurred at the peak of his artistic maturity, deprived cinema of a moral and spiritual inquiry that few other authors have been able to conduct with such depth and sensitivity. Three Colors: Red is not merely a film, but a true philosophical summa, a lucid and poignant testament to his worldview.

Red represents the conclusion of the "Three Colors" trilogy conceived by the Polish master, a triptych that, drawing upon the foundational principles of the French Revolution — Liberty, Equality, Fraternity — reinterpreted them with acute and sometimes cynical, yet always profoundly human, perspicacity. Red is the third color of the French flag, representing fraternity. But not an abstract or merely political fraternity; rather, that invisible and indissoluble network of connections that binds human existences, often without their awareness. As in Blue and White, Red also features the scene of the elderly woman struggling to dispose of her refuse, a visual leitmotif that Kieslowski elevates into a powerful symbol of urban indifference and isolation. And in this film, unlike the first two where the protagonists Julie and Dominique ignore or pass by, the protagonist Valentine helps her, performing an act of pure and spontaneous compassion, remaining true to the film's dominant theme and pointing towards a rediscovered empathy.

Valentine, a young model whose life is a kaleidoscope of appearances and ephemeral catwalks, fortuitously meets (and here, one might reflect on the entropic cynicism of Chance, or perhaps its ineluctable providence) an elderly retired judge, Joseph Kern. A man whose existence, once dedicated to formal justice, has now retreated into the shadows of an obsessive observation of others. He spies on his neighbours, intercepting their private conversations with sophisticated equipment, to satisfy his supposed sense of duty—in reality, a morbid voyeurism that is as much a search for knowledge as it is an escape from loneliness.

The judge invites Valentine to report him to the neighbours, almost challenging her, testing her morality and her sense of justice. But Valentine, after some hesitation, a subtle dance between repulsion and curiosity, decides not to, magnetically drawn to the judge, to his lucid bitterness and his clandestine spying activities. It is an attraction not of a romantic kind, but rather of intellectual and emotional resonance, almost as if Valentine recognizes in the judge's alienation a metaphor for the isolation that permeates modern society.

Valentine thus enters, with an almost Brechtian ingenuousness, the lives of the spied-upon couple, Auguste and Karin, discovering all their petty secrets, daily hypocrisies, and small lies that dot the two's lives, a bourgeois microcosm that Kieslowski dissects with surgical precision. These revelations are not merely a narrative device, but serve to unveil the fragility of facades and the often painful complexity of human relationships. The judge, for his part, is not a simple voyeur, but a disillusioned demiurge who, through his "orchestra" of others' lives, perhaps seeks to recompose a lost sense, an order in a universe he perceives as chaotic and devoid of true justice.

Embittered by the couple's plight, and perhaps by the discovery of her own emotional vulnerability, Valentine decides to join her boyfriend in England to find out if she is still in love with him, or if hers is merely an emotional dependency. On the ferry she travels on, Auguste will also be present; after discovering his wife's betrayal, he is going to London to forget, to escape a reality that has proven unbearable. A storm causes the ship to sink, a cataclysm that acts as a divine gesture, a cosmic reset that sweeps away false securities and pre-ordained plans. But the two miraculously manage to save themselves, a handful of survivors among whom, in a fleeting and metaphorical appearance, are also the protagonists of Blue and White, suggesting a common destiny, a fraternity that transcends individual narratives. And in the tragedy, they find themselves close, no longer just physically but in a deep, silent mutual understanding that goes beyond words. It is here that "fraternity" fully manifests itself, not as an ideal but as the inevitable interconnectedness of existences.

The story unfolds following two narrative registers: on one side, appearance: people appear for what they are not; their superficial crust seems to hide indecipherable abysses, social masks behind which a more complex and often uncomfortable truth is hidden. On the other side, the essence of people, their soul stripped of every adornment and exposed to public ridicule like a kind of book without a cover, in which every page reveals vulnerabilities, hopes, and baseness. This polarity is not merely stylistic, but is the pulsating heart of Kieslowski's inquiry into the human condition. The director of photography Piotr Sobociński masterfully illuminates this dichotomy, enveloping the characters in warm shades of red that clash with the cold lights of solitude, while Zbigniew Preisner's melancholic and powerful notes punctuate the emotional rhythm, anticipating and amplifying inner revelations.

A poetic dichotomy that incises like a hot blade into the lives of the characters in this story, reverberating in their uncertainties, their small basenesses, their splendid and ineffable humanity. Red offers no easy answers, but poses eternal questions about chance and necessity, observation and participation, solitude and connection. It is a film that invites us to look beyond the surface of things, to recognize fraternity not as an imposition, but as the inescapable weaving of our being in the world, a moving elegy on the infinite complexity of souls and the improbable beauty that emerges when destinies intertwine.

Genres

Countries

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...