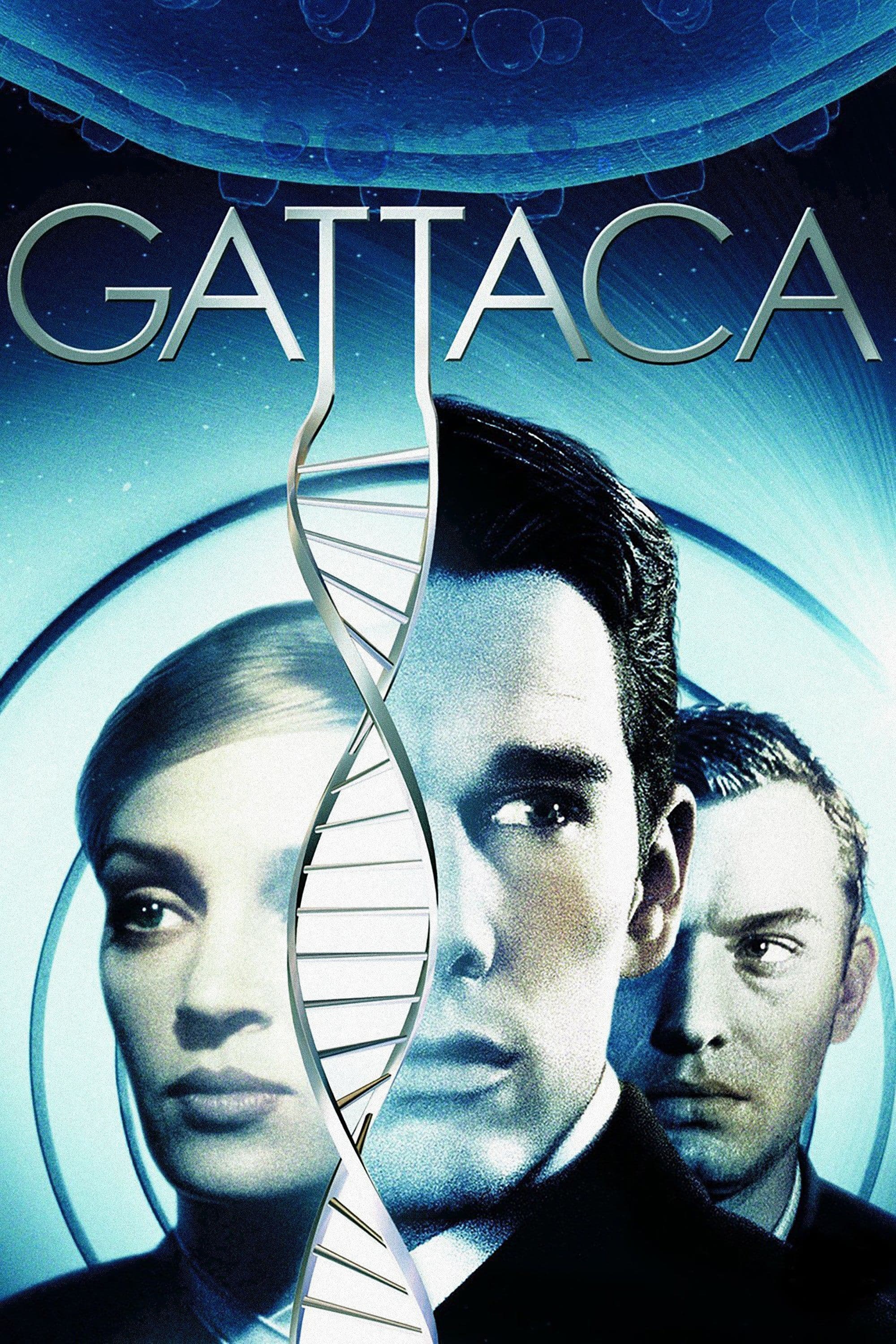

Gattaca

1997

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Andrew Niccol, a cinematic demiurge whose filmography – from the caustic Lord of War to the visionary The Truman Show (though here only as screenwriter) – has often distinguished itself by a rare sociological acuity, writes and directs a story set in a dystopian future that is not mere escapist science fiction, but a profound meditation on the most intimate fibers of our being. The beating heart of Gattaca is indeed centered on the human genetic makeup and how this, in the relentless game of increasingly refined selection, can impact the very structure of society and, with far more subtle brutality, human relationships. The work therefore stands as a lucid warning, focusing its analysis, with the precision of a genetic scalpel, on the sociological and psychological implications of genetic programming that, though a promise of perfection, proves to be the most insidious of prisons.

Gattaca is not just an aerospace agency, but an eponymous cathedral of eugenic progress that in an unspecified, yet disturbingly near, future oversees all interplanetary missions. Its architecture, a triumph of Art Deco minimalism and almost surgical cleanliness, reflects the ideal of genetic perfection pursued by a society that has elevated DNA to an unquestionable deity. In a world where society is essentially divided, with a rigidity equaling the most archaic castes, between those who have been genetically engineered – the "valids," the "born perfect" with a pre-written and optimized destiny – and those who possess the genetic heritage they received by chance from Nature, the so-called "in-valids" or "God's children," large corporations, not least Gattaca itself, use omnipresent genetic tests – a hair, a drop of blood, a skin cell – to select personnel, determining with an implacable verdict the value and potential of every individual from the cradle.

In this scenario, the dream of Vincent Freeman, interpreted with a poignant blend of vulnerability and indomitable resilience by Ethan Hawke, is to become an astronaut and travel into space, transcending the limits imposed by his genetic "imperfection." But, although he perfectly understands every theoretical and practical implication for admission – a determination bordering on obsession – he does not possess a perfect genetic code, having been born naturally and destined, according to society, to a life of humble, prospectless labor. His is a rebellion against biological destiny, a desperate cry for the affirmation of human free will.

The turning point comes with the crucial and almost Faustian encounter with Jerome Morrow, a crippled young man, reduced to living in a wheelchair after a suicide attempt, but possessing a golden DNA, a genetic heritage so impeccable as to make him a precious commodity in this distorted world. Their relationship, an almost symbiotic and perversely functional pact, will irrevocably change Vincent's life, providing him with the "valid" identity needed to infiltrate the system. The device of "genetic identity theft" becomes the lens through which Niccol explores not only the superficiality of a society obsessed with biological appearance, but also the unexpected depth of human bonds that can emerge outside of any genetic parameter.

The future of Gattaca is, in truth, not too far off, and much of its disturbing power resides precisely in this tangible proximity. A society that determines an individual's aptitudes, propensities, even longevity and predisposition to failure through human DNA seems alarmingly plausible, and it is even more so today, with the advancements in bioengineering and CRISPR technology hinting at scenarios on the horizon that were once pure science fiction. The film, released in 1997, extraordinarily anticipated ethical debates that would become central with the advancement of the Human Genome Project.

Although Vincent's character strives to demonstrate with every fiber of his being that genetic programming does not make one individual more qualified than another, that true excellence lies elsewhere, beyond mere chemical code – "There is no gene for destiny," Vincent exclaims in one of the film's most memorable and significant lines – there remains a subtle horror lurking beneath the narrative's surface, a palpable disquiet that does not stem from monsters or apocalyptic cataclysms, but from the cold logic of eugenics applied on a large scale, leaving a lingering sense of unease in the viewer. The iconic scene of the swimming race against his genetically superior brother, Anton, where Vincent triumphs not thanks to his biological superiority, but through sheer force of will and the ability to "save nothing for the swim back," embodies the heart of his philosophy.

Andrew Niccol's film thus delves, with a taut narrative and a visual aesthetic of rare elegance (thanks to Sławomir Idziak's cinematography and Michael Nyman's melancholic notes), into the mysteries of the human genome, giving rise to an existential thriller that leaves open questions not only about chromosomal heritage and possible manipulations that pursue the distorted utopia of a "chosen race," but also about the true nature of merit, identity, and free will. It is a profound meditation on our obsession with perfection, a perfection that, as Jerome's tragic fate teaches, can prove to be the greatest of prisons, while imperfection and the struggle against it can be the spark that ignites true human greatness. Gattaca is, ultimately, an ode to the indomitable human spirit, a warning against the temptation to reduce the complexity of the soul to a sequence of letters, and a powerful affirmation that destiny, after all, is still something we are called to write with our own hands, beyond any supposed genetic predetermination.

Country

Comments

Loading comments...