The Banshees of Inisherin

2022

Rate this movie

Average: 4.67 / 5

(3 votes)

Director

Martin McDonagh's The Banshees of Inisherin is a philosophical parable disguised as a black comedy, a work that possesses the density of a Samuel Beckett play and the desolate beauty of an Andrew Wyeth painting. It is a requiem for kindness in a world that has chosen despair as an art form. McDonagh's genius lies in his ironic verve, a writing style that crackles like embers beneath the ashes of a grey and melancholic world. The dialogue is a masterpiece of rural wit and existential depths. There is much laughter, but it is laughter that chokes in the throat. We laugh at Pádraic's "dullness," his obsession with his donkey, but McDonagh is asking us: is it more important to be an "interesting" man or a "kind" man? The answer is far from obvious. The irony is never an end in itself; it is the scalpel with which the director dissects the surface of normality to reveal the void that lies beneath. The funniest line is always a step away from the darkest tragedy.

The film is a duel between two worldviews, embodied by two unforgettable men. Pádraic (Colin Farrell): he is the simple man, perhaps even dull, whose life is punctuated by small routines and sincere affections. He represents decency, community, kindness as a foundational value. His despair, when this world is torn from him, is that of a good man told that his goodness is worthless. Colm (Brendan Gleeson): He is the artist, the intellectual, the man who, looking into the abyss of his own mortality, decides that the only thing that matters is leaving a legacy. His crusade against boredom is a desperate, and at times cruel, fight against time. To pursue immortal music, he is willing to mutilate himself and his humanity.

Colm's act of cutting off his fingers with sheep shears is not merely a plot twist. It is the philosophical pivot of the film, a gesture of violence as absurd as it is dense with meaning, made even more unsettling by its almost rustic context. In an urban or intellectual setting, such an act might be interpreted as an artistic performance, however extreme. But on Inisherin, an island where hands are used for fishing, for farming, for playing the fiddle at the pub, and where the instrument of torment is sheep shears—a raw and brutal tool of work—the mutilation takes on a terrifying concreteness. There is nothing abstract about it. It is a gesture rooted in earth and blood, an eruption of primordial chaos into the monotony of rural life. This contrast between pastoral tranquility and self-inflicted violence tells us that the desert of Colm's soul has become so arid that the only thing that can grow there is physical pain. The meaning of the gesture is a dizzying paradox. Colm claims he wants to sever his friendship with Pádraic to dedicate the time he has left to art, to composition, to leave a legacy that will save him from the despair of nothingness. And to demonstrate the seriousness of this artistic vocation, what does he do? He destroys the very instrument of his art. He cuts off the fingers with which he plays the fiddle.

In this seemingly illogical act lies the truth: Colm's despair is not merely artistic ambition; it is an existential abyss so profound that art itself becomes secondary. The gesture becomes more important than the music. The mutilation is his true, ultimate composition: a grotesque and desperate work of art, sculpted in his own flesh. It is his way of screaming to the world—and especially to Pádraic—a pain he can no longer contain or articulate in words. It is the transformation of inner torment into a visible, undeniable wound. And all this occurs as an interposed element in the conflict between the two men, almost sealing the monstrous divergence between their two opposing worlds.

This conflict is not between a "good" person and a "bad" person, but between two fundamental human needs that are, in this case, irreconcilable: the need for connection and the need for meaning. The island of Inisherin, with its poignant and monotonous beauty, is not merely a backdrop. It is the third protagonist, a desolate land of the soul echoing T.S. Eliot's poem. While a senseless civil war rages on the mainland (heard only through distant rumbles), an equally absurd civil war unfolds on the island between two men. It is a world where communication has broken down, where old bonds are severed for no apparent reason, and where characters, like the prophetess Mrs. McCormick, are spectral figures announcing impending death. The landscape is a spiritual desert where man questions his own existence, finding only the silence of the sea and the wind.

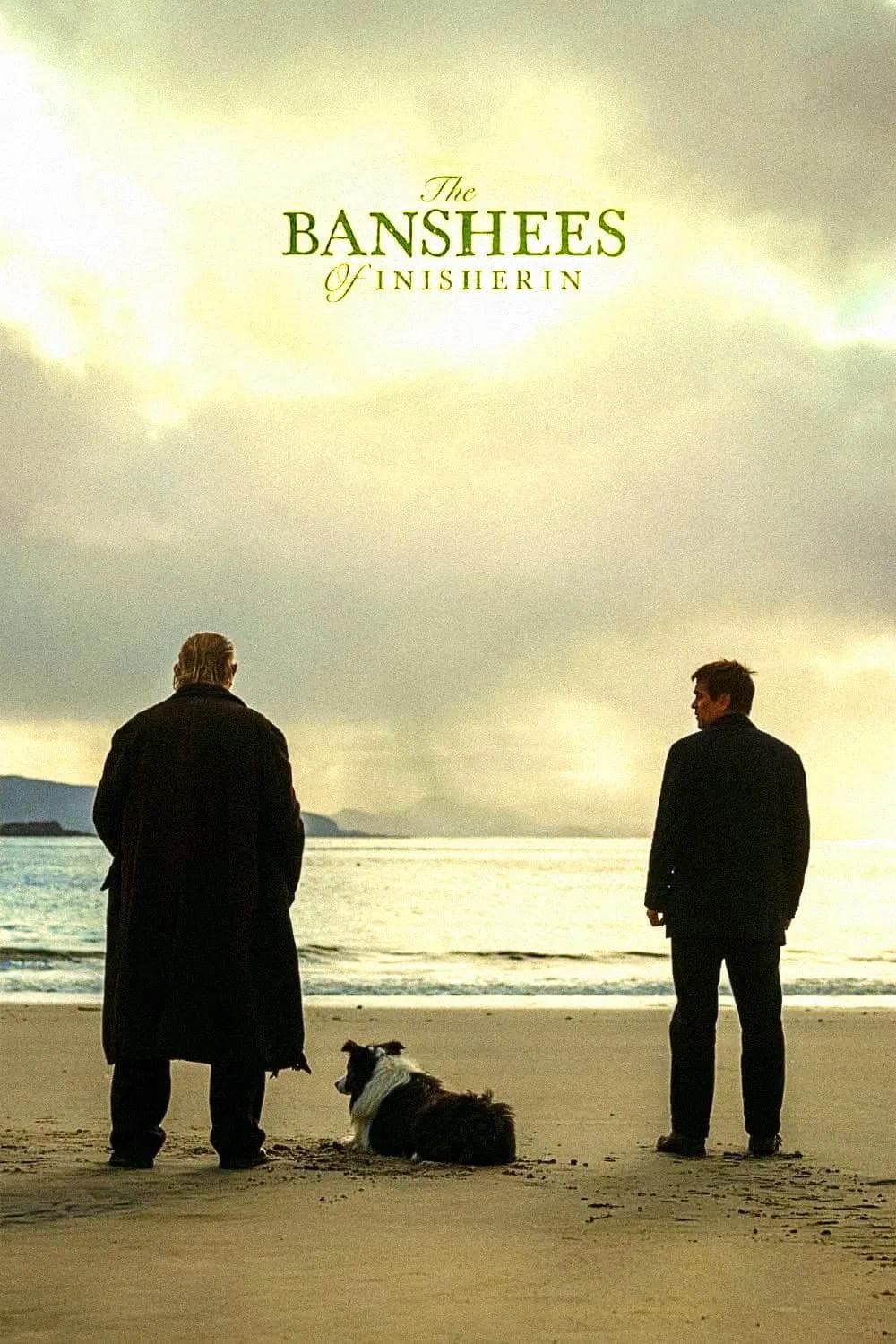

Yet, and this is the film's supreme genius, The Banshees of Inisherin is, paradoxically, a film about the indelible power of friendship. The violence and absurdity of Colm's actions are the exact measure of the depth of the bond he wishes to sever. One does not undertake such extreme gestures for something one does not care about. The sacred fire of that friendship, even in its act of extinction, releases a blinding and destructive heat. In the end, when the two men stand on the beach, enemies yet forever bound by what they have shared and destroyed, we understand that that bond is not over. It has simply transformed into a scar, a shared pain that, in its own way, is still a form of connection. Despite everything, in that desert, something still pulses.

Gallery

Featured Videos

Trailer

Memorable Scene

Comments

Loading comments...