Good Bye, Lenin!

2003

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Let's be clear from the outset: this film is such an intelligent comedy that it manages to laugh at a collective trauma, which the fall of the Wall and the transition to a democratic system for all East Germans effectively represented. But to simply define it as a comedy would be reductive, almost a lèse-majesté towards its layered depth. Wolfgang Becker does not merely elicit laughs; he dissects with surgical precision and unusual tenderness an era, a historical watershed that redefined not only political geography but also the intimate identity of millions of individuals. The fall of the Berlin Wall, in fact, was not merely a geopolitical event, but rather a hurricane of freedom and, paradoxically, disorientation, which swept away consolidated certainties, habits, and even an entire collective imagination, leaving behind a void as material as it was psychological. Becker's film tackles this dizzying loss with a sagacity that elevates the comedic genre into a vehicle for sociological and anthropological reflection.

The story is that of Christiane, a woman whose existence, until that moment firmly anchored to the principles and routine of the German Democratic Republic, is abruptly interrupted by a heart attack that plunges her into a coma, precisely as History, with a capital H, is making its most unpredictable of leaps. Upon awakening, “after the dust had settled,” as the saying goes, she finds herself catapulted into a radically transformed universe, an urban and cultural landscape now unrecognizable, imbued with the symbols of Western capitalism.

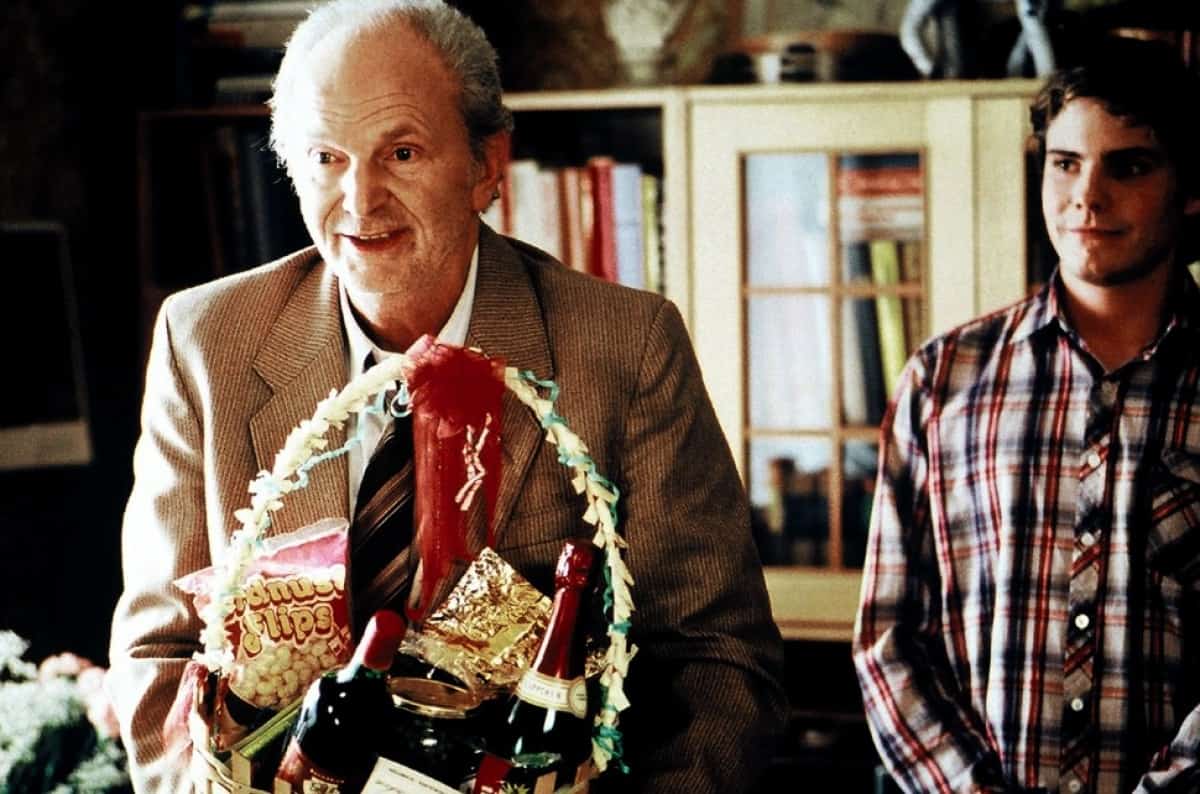

Her son Alex, played by a Daniel Brühl in a state of grace, a young man already oriented towards the dynamics of the new West but still deeply connected to his family and emotional roots, embarks on a mission of filial pietas of epic proportions. His intent is not only to harmonize his mother's return into a capitalist society marked by new rhythms and ideals, but it is a race against time to protect her emotional fragility, to preserve a heart already tested by old private wounds and now threatened by a cultural shock of unprecedented violence. He soon realizes that the only way to protect her is to make her believe she is still under the reassuring aegis of communism.

Hence the idea of building her a kind of protected environment where everything was traceable to the old way of life. This is not a simple pretense; it is an ephemeral work of art, a gigantic performative installation in which Alex, with the help of his cinephile friend Denis, recreates a simulacrum of the GDR. Every detail is maniacally crafted: food labels exhumed from trash cans and glued onto new Western packaging, period music played on crackling vinyl, and, above all, fabricated television news reports. These surreal editions of "Aktuelle Kamera" – the GDR's news program – narrate an alternative history in which the West dissolves, the Wall remains standing, and even Coca-Cola becomes a socialist invention. Here the film reaches peaks of brilliant metaphor, transforming media into a vehicle for a constructed "truth," not dissimilar to certain contemporary drifts regarding disinformation, but here animated by a noble filial intent. One could almost discern an echo of Jean Baudrillard's theory of simulation, where the copy becomes more real than the original, and nostalgia, the celebrated Ostalgie, is not just a feeling, but a true mechanism of identity defense.

Plaudits to Wolfgang Becker for finding lightness, levity, and self-irony in such a dense context. His direction strikes a precarious and sublime balance between the most exhilarating farce and the most intimate drama. He neither demonizes nor glorifies the socialist past; rather, he captures its human essence, its small joys and daily absurdities, with a sincere yet never naive affection. The sequences in which Alex and Denis scramble to maintain their elaborate charade are pure comedy of errors, but with an underlying melancholy that elevates every laugh. Martin Kukula's cinematography contributes to this effect, alternating the desaturation of colors that evokes the image of the GDR – sometimes with warm, nostalgic tones, other times with an almost claustrophobic grayness – with the blinding brightness of new capitalism, with its luminous signs and glittering products.

The work is intelligent, in many ways irreverent, yet always with a bitter and suspended underlying lyricism. Irreverent because it dares to laugh at sacred symbols and still-open wounds, revealing the absurdity of certain ideologies and the fragility of official narratives. But its lyricism emerges in the profound humanity of the characters, in the portrayal of the indissoluble bond between mother and son, and in the painful acceptance that the past, however idealized or criticized, is irrecoverable. The ending, in particular, is a masterpiece of sweetness and illusion, where Alex's "perfect lie" not only protects Christiane but grants her a dignified and, in a sense, epic exit. It is a film that questions us about the nature of collective and individual memory, about the truth that sets us free and the lie that can, at times, protect us. A hymn to the human capacity for adaptation, but also a lament for what is inevitably lost in the inexorable progress of History. Becker's film is not just a historical document disguised as a comedy; it is a universal ode to the resilience of the human spirit in the face of existential quakes.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...