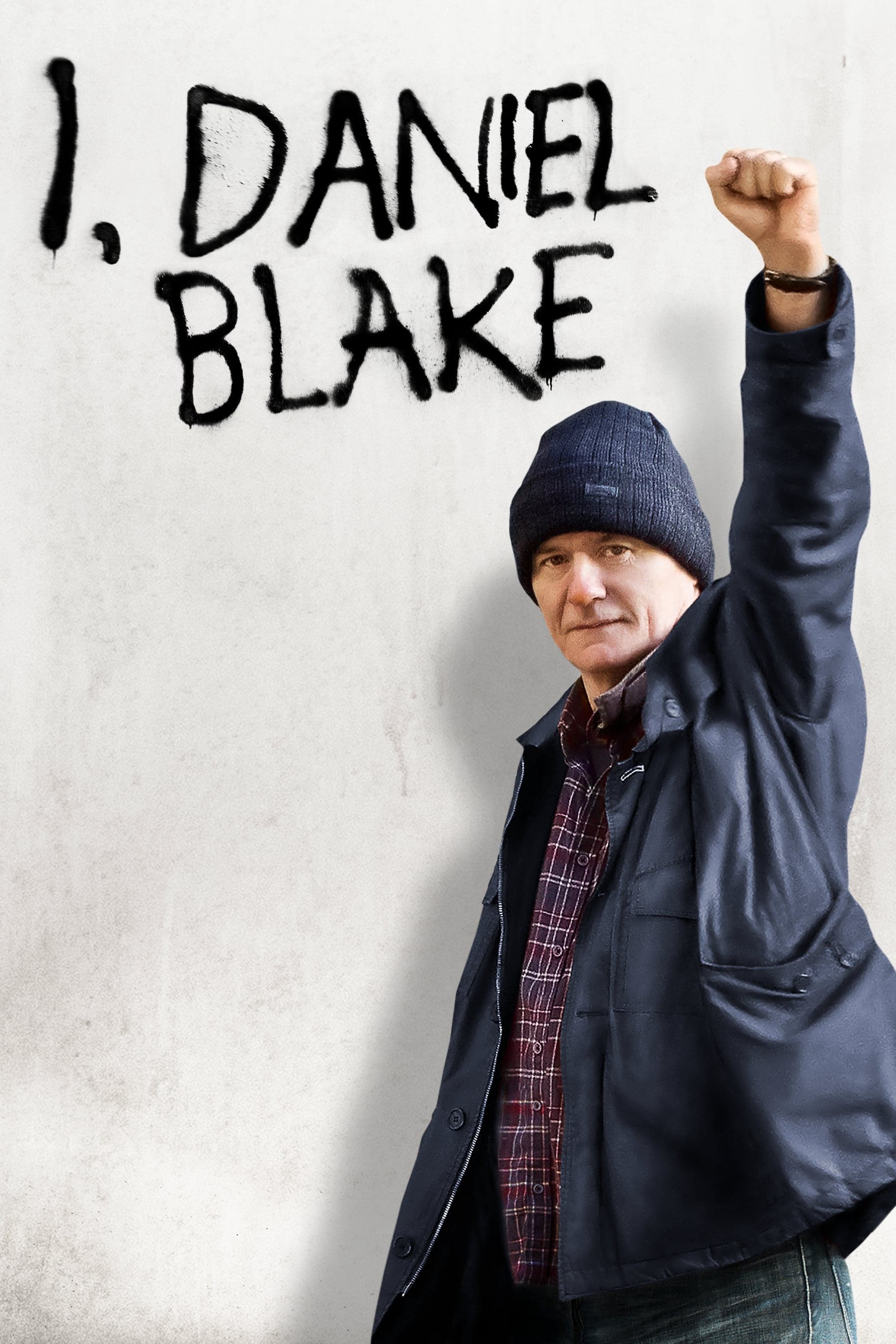

I, Daniel Blake

2016

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

Winner of the Palme d'Or at Cannes in 2016 and numerous other awards, this film crowns the great cultural and political commitment of Ken Loach, a British director who has always been sensitive to themes of social injustice, oppression, and disparity that turn the humblest class into a kind of lightning rod, upon which every kind of aberration of the so-called Rule of Law descends.

Ken Loach's films have always been a vehicle for incisive criticism of an unbalanced, unjust, and oppressive system. They are never mere political didacticism, but rather an almost documentary-like immersion into the daily lives of marginalized existences, often invisible to the eyes of affluent society. His aesthetic, rooted in the tradition of British social realism – from Free Cinema to "kitchen sink drama" – manifests through a dry, essential direction that shuns any stylistic baroque excess to focus on the raw truth of the characters and their circumstances. The fundamental contribution of Paul Laverty, Loach's long-standing screenwriter, is evident in his ability to weave intimate and personal narratives that resonate with universal issues, elevating individual stories to collective metaphors. The frequent use of non-professional actors or little-known faces contributes to that sense of authenticity that is the distinctive hallmark of his cinema, a cinema that does not spectacularize pain but exposes it with dignity.

One of Ken Loach's most famous quotes perfectly expresses his idea of cinema: "A film is not a political movement, nor a party, nor even a newspaper article. It's just a film. And the best it can do is add its voice to public outrage for every injustice." This statement reveals the programmatic modesty of a filmmaker who, despite having a crystal-clear political agenda, understands the limitations of his medium, but also its ineluctable strength as a sounding board for unheard cries. Loach is the director of the invisible, of the voiceless, of those marginalized due to their social condition, or their skin color, or simply because they are exploited by an economic mechanism that crushes manual labor for the consolidation of capital. He does not merely show us these figures, but elevates them to witnesses and, in some cases, to martyrs of a system that does not want or know how to recognize their inherent dignity.

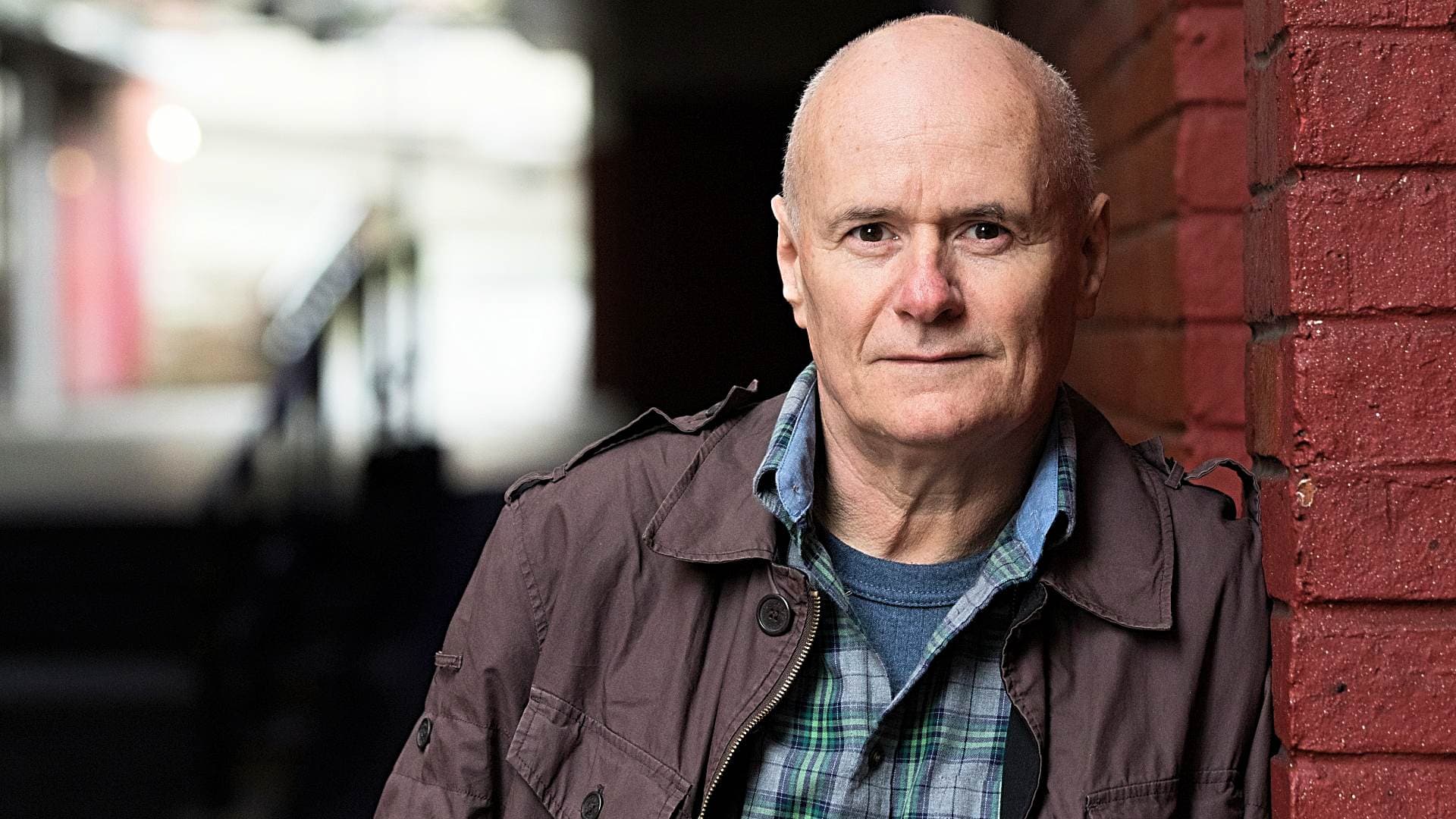

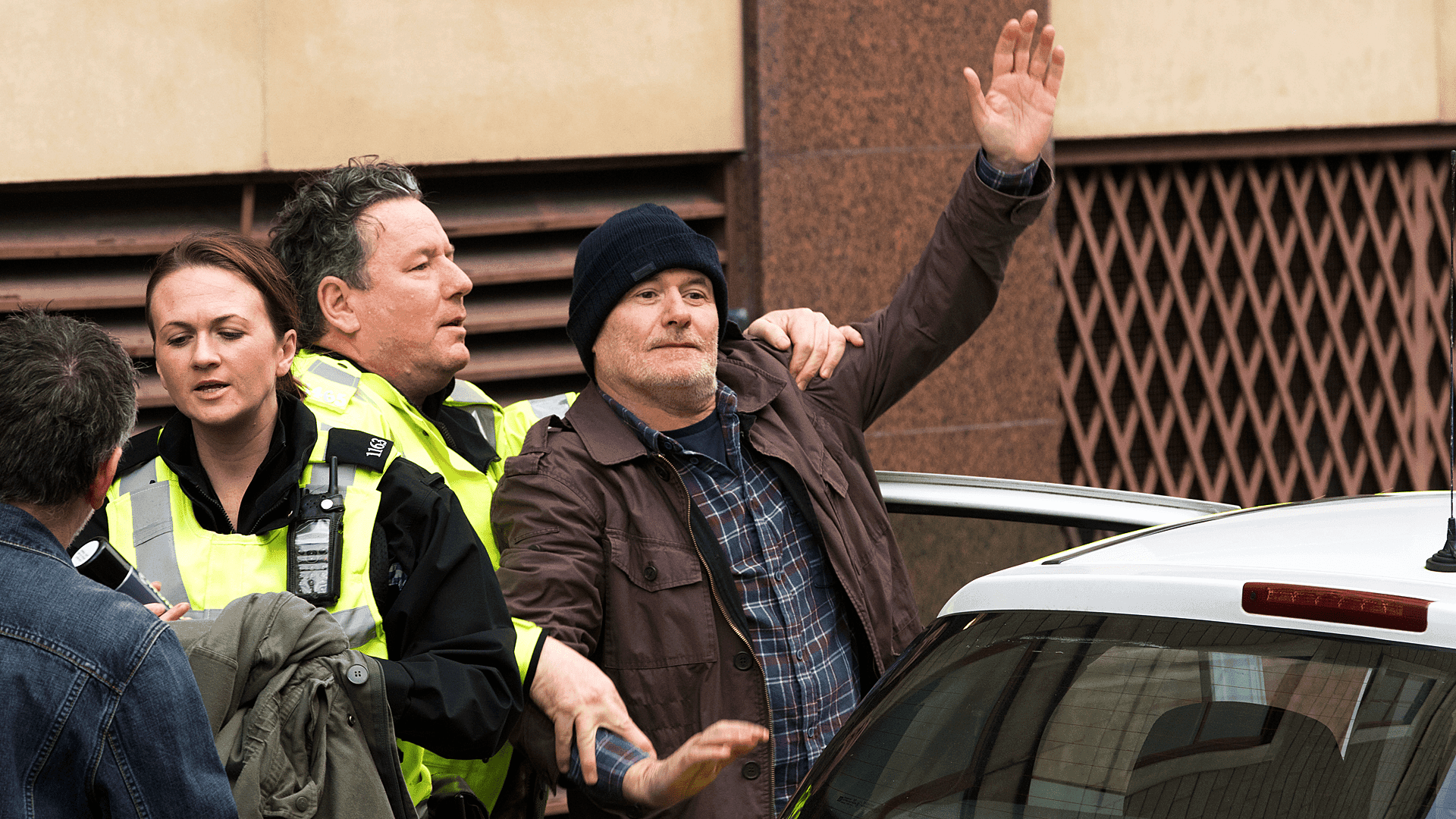

Daniel Blake thus becomes a symbol of opposition, of furious rebellion against this unbearable pressure that crushes the lowest strata of society from above, an ordinary man who raises his battle cry. He is not the hero of an epic, but the embodiment of daily resistance, whose strength lies precisely in his normality and the disarming simplicity of his demands: to be treated with respect. Daniel Blake is a respected carpenter from Newcastle. Reaching the age of 60, he is struck by a serious heart condition that renders him unable to work. Thus begins his bureaucratic ordeal to apply for state benefits determined by his illness.

An ordeal that, in an era of austerity policies post-2008 financial crisis, becomes the burning metaphor for an England (but by extension, a West) that has chosen to cut ties with its most vulnerable citizens, transforming the welfare state from a safety net into a punitive labyrinth. Daniel thus plunges into the sharp gears of English bureaucracy, a perverse mechanism where the applicant is bounced from one office to another after interminable phone waits, where he is humiliated by degrading medical examinations that question his very perception of pain, where he is submerged by countless forms to fill out, often digital, in an era where the digitalization of public services creates an insurmountable gap for those who are elderly, lack access, or computer skills. The Kafkaesque description of this system, which seems to exist only to self-perpetuate and wear down the citizen, is one of the hardest blows delivered by Loach. There is no face to evil, but an anonymous and dehumanizing organization, where every counter, every operator, is merely a cog in a larger, more ruthless mechanism.

Daniel soon realizes that while waiting for the much-desired benefit to arrive, he will have to find undeclared work to survive, although this entails the risk of a harsh penalty if discovered. His dignity as an honest worker, a law-abiding citizen, is compressed and trampled by the very institutions that should protect him, pushing him to the margins of legality for the sacred necessity of eating. In one of his pilgrimages from one government office to another, Daniel meets Katie, a single mother of two children, also a victim of the fierce bureaucracy. Their stories, though different in age and background, mirror each other, revealing the systemic nature of the oppression. The film does not spare the viewer the most atrocious scenes, such as when Katie, overcome by hunger and shame, opens a can of beans and frantically eats it at a food bank, bundled up with her broken dignity, under Daniel's helpless and sorrowful gaze. It is a moment that pierces the stomach and soul, making palpable the abject degradation to which the system pushes individuals.

Daniel fights for her because he recognizes in her a victim just like himself, a person adrift upon whom the system mercilessly descends. This act of empathy, of solidarity, is the beating heart of the film, an antidote to the toxicity of bureaucratic indifference. The paternal relationship between the two is key to understanding the film, a wonderful work of rapprochement between two entirely different souls united by harsh contingency. Affection, mutual aid, the rediscovery of a sense of community – themes dear to Loach, often celebrated in his films – emerge here as the only, untamed resistance to the forced individualism imposed by dominant economic logics.

A film that first and foremost moves with the strength of its humanity, with the power of a language that makes solidarity and fraternal cooperation among people the only bulwark of civilization. In this sense, "I, Daniel Blake" fits into a noble tradition of social critique cinema, from Vittorio De Sica's Umberto D. – with its poignant and disarming portrait of an elderly man grappling with loneliness and the cruelty of an indifferent world – to the films of the Dardenne brothers, who with their realistic aesthetic and focus on the marginalized have charted a similar path in the heart of Europe. The power of Loach's film lies in its ability to make us feel the coldness of the algorithm on the characters' skin, to make us perceive the echo of automatic responses and impersonal denials as veritable slaps. The final scene, with the emblematic eulogy, is not only the conclusion of an individual story but a devastating indictment, a bitter catharsis that transforms mourning into a collective cry.

Daniel is a hero of our time, an invisible shadow that passes us by among thousands of other human beings, a light that shines ever more brilliantly in a context of indifference, of total apathy. Daniel is us, as we would like to be, as we should be: people who care about others in difficulty, men and women who strenuously oppose the modern drift away from every most elementary feeling of human collaboration. A work that not only tells a story but pushes us to reflect on the very meaning of "civilization" in an era of growing inequality and dehumanization, reminding us of the inestimable value of dignity and compassion.

Main Actors

Genres

Countries

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...