The Killers

1946

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

In a squalid, fourth-rate hotel, a man waits with disillusioned resignation for the arrival of the hitmen. It is not merely a wait, but a lucid, almost stoic acceptance of his fate, an act of surrender preceding death, imbued with a palpable melancholy that Robert Siodmak’s camera captures with disarming effectiveness. The cold precision of the dialogues, the impenetrable calm of the imminent victim, Ole Andreson, nicknamed "the Swede," are details that etch into the viewer’s memory an image of ineluctable fatalism, a prelude to an investigation as much noir as it is existential.

One of Hemingway’s most fascinating stories begins with this striking mise-en-scène, its laconic prose, steeped in a philosophy of omission – the famous "iceberg theory" – finding in Siodmak an exceptional visual interpreter. The director, with a mastery that transcends simple transposition, succeeds in making the implicit tangible, in suggesting inner worlds and submerged dramas solely through the power of images and atmosphere. The brutalist elegance of Hemingwayan narration, where the unsaid weighs as much as the said, is mirrored in the cinematographic grammar of noir, made of dense shadows, eloquent silences, and faces that conceal as many secrets as they reveal.

Siodmak works admirably on the Hemingwayan material by focusing his camera’s lens on the protagonist’s figure, probing every hidden emotion and returning it in the form of pure essentiality, stripped of all unnecessary formal embellishment. His approach is that of a carver, capable of distilling the tragic essence of an existence. The profound influence of German Expressionism, a movement of which Siodmak had been a pioneer before emigrating to Hollywood, manifests itself in every shot, in every interplay of light and shadow that is not mere embellishment, but a structural element of the psychological narration. Chiaroscuro is not merely style, but a language that expresses moral corruption, the blurring of good and evil, the very nature of fate gathering around the characters. It is a ballet of light and shadow that envelops the Swede, revealing his fragmented past and his intrinsic, desperate solitude.

Hemingway himself admitted that this film was the only one that had truly captured the spirit of his work. A statement that sounds like an investiture, an acknowledgment of Siodmak’s ability to preserve the thematic and tonal integrity of the original story, without succumbing to the sirens of gratuitous spectacularization or emotional over-explanation. Unlike other, often failed, transpositions of his works, I Gangsters does not betray the dryness, the implied violence, and the relentless fatalism that are Hemingway’s trademarks, but rather enhances them, makes them visceral through an aesthetic that becomes almost tactile. The sense of inevitability, the resignation in the face of a pre-written destiny, are rendered with a visual power that equals, if not surpasses, the evocative force of the written word.

After the killing of the Swede, an act that serves as a focal point rather than an epilogue, the patient weave of flashbacks will begin, laying bare the man's life and the reason for his tragic end. This non-linear narrative structure, a classic noir film device, here becomes an almost forensic investigative tool, a journey back into the folds of memory and betrayal. The investigator, the tenacious but disillusioned Riordan (played by an excellent Edmond O’Brien), is not the typical problem-solving hero, but rather an archaeologist of others' pain, who assembles the fragments of a broken existence. Each flashback, a tile in a tragic mosaic, reveals layers of deceit, shattered ambitions, and cursed loves, until it forms the complete picture of an inexorable fall. Time, in noir, is often a labyrinth from which one cannot escape, and here it is more than ever, with the past inexorably predetermining the present and sealing the future.

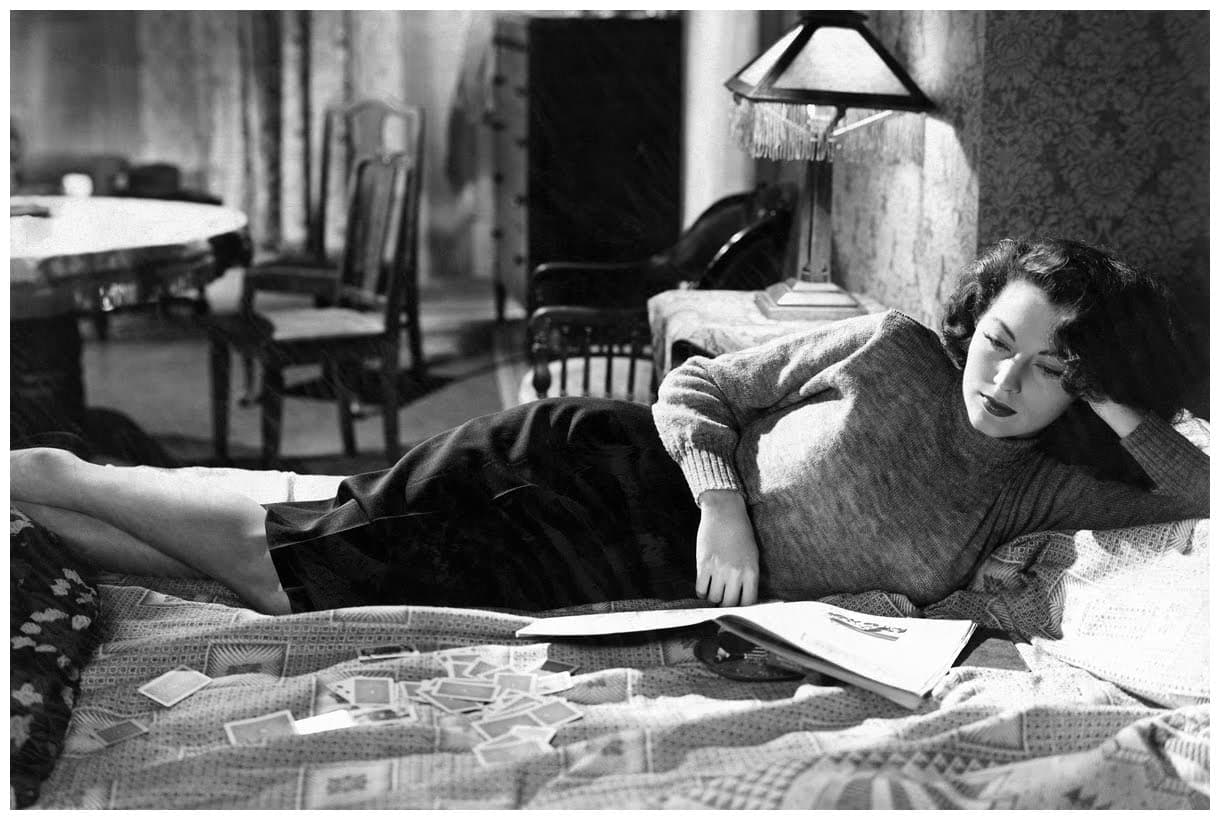

A film that indelibly marks the noir genre, consolidating many of its most iconic tropes and elevating its stylistic hallmark, featuring a great Burt Lancaster in his striking cinematic debut. His portrayal of the Swede, combining an imposing physicality with an almost childlike vulnerability, perfectly embodies the archetype of the fated anti-hero, a boxer whose last fight is against an implacable destiny. Alongside him, a sensational Ava Gardner takes on the role of Kitty Collins, the quintessential femme fatale: a creature of blinding beauty and lethal duplicity, whose mere presence promises both salvation and damnation. She is the magnetic focal point of the tragedy, the disruptive element that diverts the course of the Swede’s life towards an abyss of no return. And above all, an even greater director in the role of Demiurge of emotions, an invisible puppeteer who sagaciously plays with the viewer's morbid curiosity, leading them with a firm hand through the labyrinth of a lost soul and the dark peripheries of a hopeless city. Miklós Rózsa’s score, with its nervous and melancholic themes, further amplifies this growing sense of despair, cementing I Gangsters not only as a noir masterpiece but as a milestone in the representation of human fragility in the face of the adverse currents of fate and temptation.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...