Fists in the Pocket

1965

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Debut film for a director who never embraced compromises, and who, indeed, from this dazzling debut work, imposed a radical gaze, a scathing social and psychological critique, destined to forge a unique authorial path in the Italian and international cinematic landscape. Bellocchio, with "Fists in the Pocket", does not merely break conventions; he pulverizes them, ushering in a season of highly personal cinema that rejects both the dictates of dying neorealism and the sterile fascinations of a more polished and conciliatory cinema. His approach is that of an intellectual provocateur, steeped in the Marxist and psychoanalytic readings that animated the cultural ferment of the 1960s, a period of deep social tensions and generational rebellions.

And Bellocchio's spirit is perfectly infused also in this debut work where a family drama is vivisected with almost scientific rigor, a clinical dissection that allows no space for pietism or easy consolations, laying bare its dark recesses and murky implications. The camera becomes an inquiring eye, an implacable scalpel that penetrates the bourgeois surface to reveal a universe of latent pathologies, of latent dysfunctions exploded into violence that is both physical and emotional.

The story is set in the Piacenza area, in Bobbio, a place that for Bellocchio is not just a backdrop, but a true metaphorical epicenter. The house where the action unfolds is not a nest, but a prison, a claustrophobic microcosm in which the family, archetype of the social cell, is reduced to a tangle of neuroses and sick interdependencies. It is a bourgeois family, a blind widow living with her four children, an embodiment of a social class that, beneath its respectable surface, conceals moral putrefaction and an inability to confront modernity. It is a Bourgeois with a capital B that Bellocchio intends to unmask, a symbol of an Italy in transition, still bound to old hierarchies and values, but already undermined by a deep malaise.

One of these children, Alessandro, has character problems combined with an epileptic pathology. His epilepsy is not a simple medical diagnosis; it manifests as the somatic expression of a deep existential unease, the boiling over of an imprisoned and rebellious psyche. Alessandro is the fulcrum of this implosion, the catalyst of destruction. In a mad scheme, he will plan the killing of his mother and a mentally handicapped brother, citing humanitarian pretexts, a perverse logic that mixes twisted pity and a desire for liberation, not only for himself but for the entire family, trapped in a limbo of non-life. He will begin a morbid and consuming endeavor to put his hallucinated death project into action, a plan that is not the result of mere madness, but of a lucid, albeit sick, awareness of the unsustainability of their existence. His determination recalls that of certain Dostoevskian characters, driven by a reason that, though deviant, imposes itself with ineluctable force.

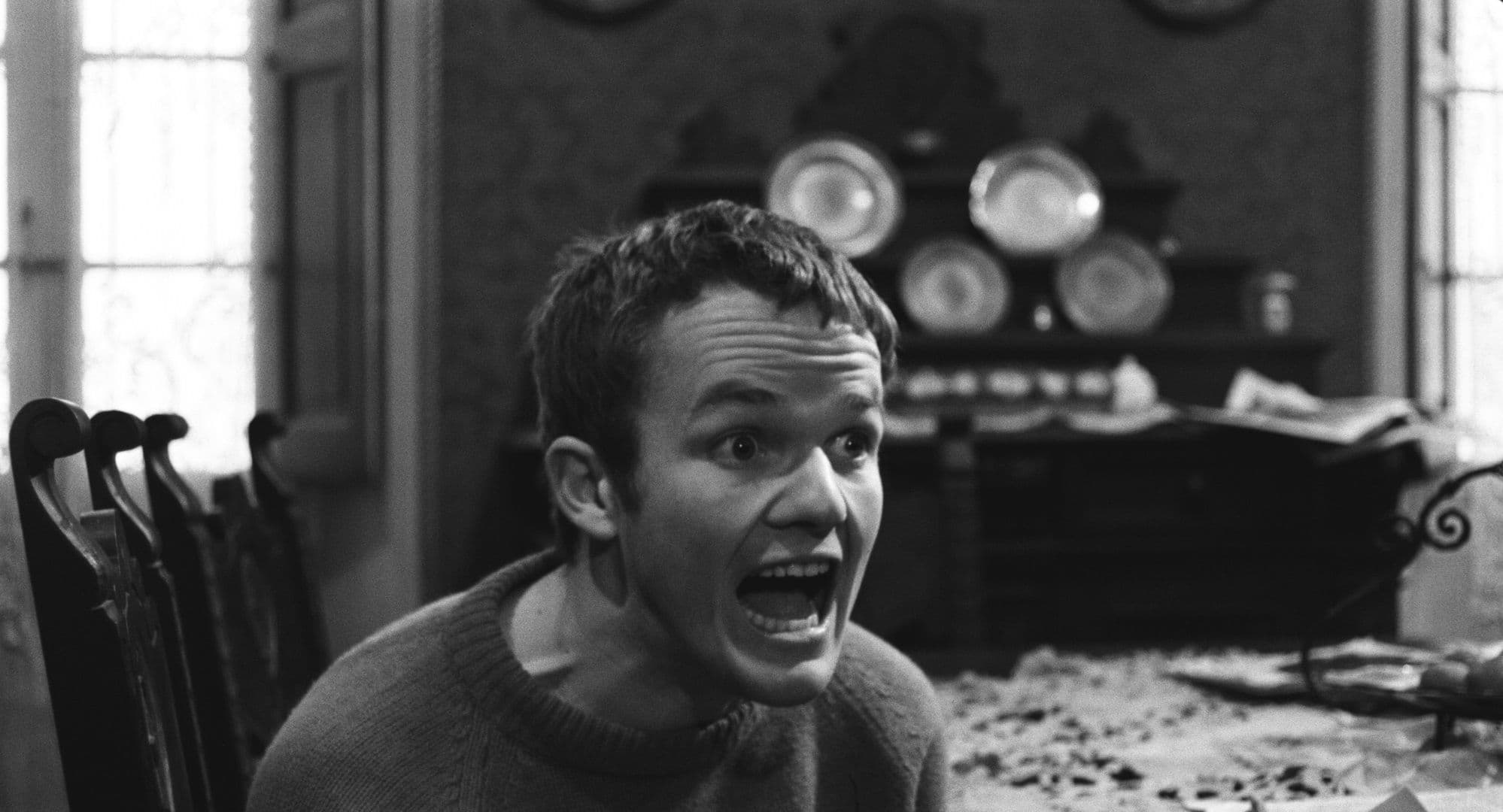

A film that exudes anguish and in which Alessandro is the Deus ex Machina and the sacrificial victim, the Demiurge and the Madman. He is a "deus ex machina" who does not resolve, but triggers catastrophe, a puppet master of a drama he himself embodies. His "madness" is a vehicle to denounce the pathological "normality" that surrounds him, a magnifying glass on hypocrisies and repressions. Behind his sick mind, one glimpses Bellocchio's cold and sharp gaze, his ability to move characters and flay their psychological sphere. The director does not judge, but shows, with almost surgical lucidity, the ineluctable progression towards the abyss, orchestrating every movement, every shot, to accentuate the growing tension and sense of suffocation. The use of close-ups, often insistent and brutal, amplifies this sensation, making the viewer an uncomfortable witness, almost an unwitting accomplice to the unfolding tragedy.

Among all the striking scenes, we select one perhaps paradigmatic: the dinner. This sequence, an archetype of the "table drama" that would find echoes in subsequent films, from Buñuel to Pasolini, is a showcase of pathologies and repressions. The family is gathered at the table, and Alessandro moves nervously in his chair, a constant tremor that reveals his repressed energy and growing impatience. The camera follows his sudden movements with brutal close-ups of his arm resting on the furniture behind him, of his legs bothering his sister under the table, of his face snapping at his brother, guilty of eating improperly. Every gesture is an electric discharge, a symptom of his rebellion not yet exploded, but already pulsating. Throughout the long scene, a surreal silence reigns, heavy as a millstone, interrupted only by the meows of the house cat climbing onto the table to steal food from the blind mother's plate. The animal, with its primary instinct and its indifference to human conventions, becomes a disturbing element, almost a duplicate of Alessandro's irrational, yet so authentic, behavior. The cat's theft of food from the blind mother's bowl is not a random detail; it is a violation of order, an insubordination that prefigures catastrophe, a vivid image of the moral decay creeping among the family members.

A work in black: bleak and compelling in its anxieties, "Fists in the Pocket" remains a seminal film, not only for Bellocchio's cinema but for the entire European cinematography. Its strength lies in its ability to delve into the depths of the human soul, revealing the darkest impulses and self-destructive mechanisms that can nest even in the most conventional of family contexts. It is a punch to the gut that never stops hurting, a film that, decades later, maintains its subversive power and its unsettling relevance intact, inviting the viewer to confront their own dark side and the often invisible cracks that run through the facade of normality.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...