Le Cercle Rouge

1970

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

A work that builds its semantic heritage on the silence of marginality, weaving a tapestry of profound meanings that emerge not so much from explicit dialogue as from measured actions and gazes laden with unspoken words. In this Melvillean universe, eloquence resides in the absence of superfluous noise, in the minimalism that elevates gesture to a declaration of intent. Marginality, here, is not just a social condition of its anti-heroes, but an existential choice, a kind of secular monasticism that isolates them from the din of the ordinary world, making them almost archetypal figures, devoid of superfluous ties but bound by an invisible code of honor.

Jean-Pierre Melville, a true architect of cinema crafted with almost surgical precision, emerges as the undisputed master of a solitary humanity, destined to cross paths at the crossroads of chance and fate. At this juncture of destinies, he does not merely recount a simple robbery, but defines the rules of an existential game in which three men, moments before perfect strangers, are fatally drawn to one another for a common project: to rob a jewelry store. But what unites them is not just greed or necessity; it is an elective affinity dictated by an unwritten code, a kind of criminal deontology that, in the Melvillean vision, becomes more stringent and noble than many civil laws. The plot of the "perfect heist" thus becomes a pretext for exploring the depths of these bonds forged in the steel of determination and the precariousness of existence, in a constant echo of American noir that greatly influenced the director, but reinterpreted through an exquisitely French philosophical lens.

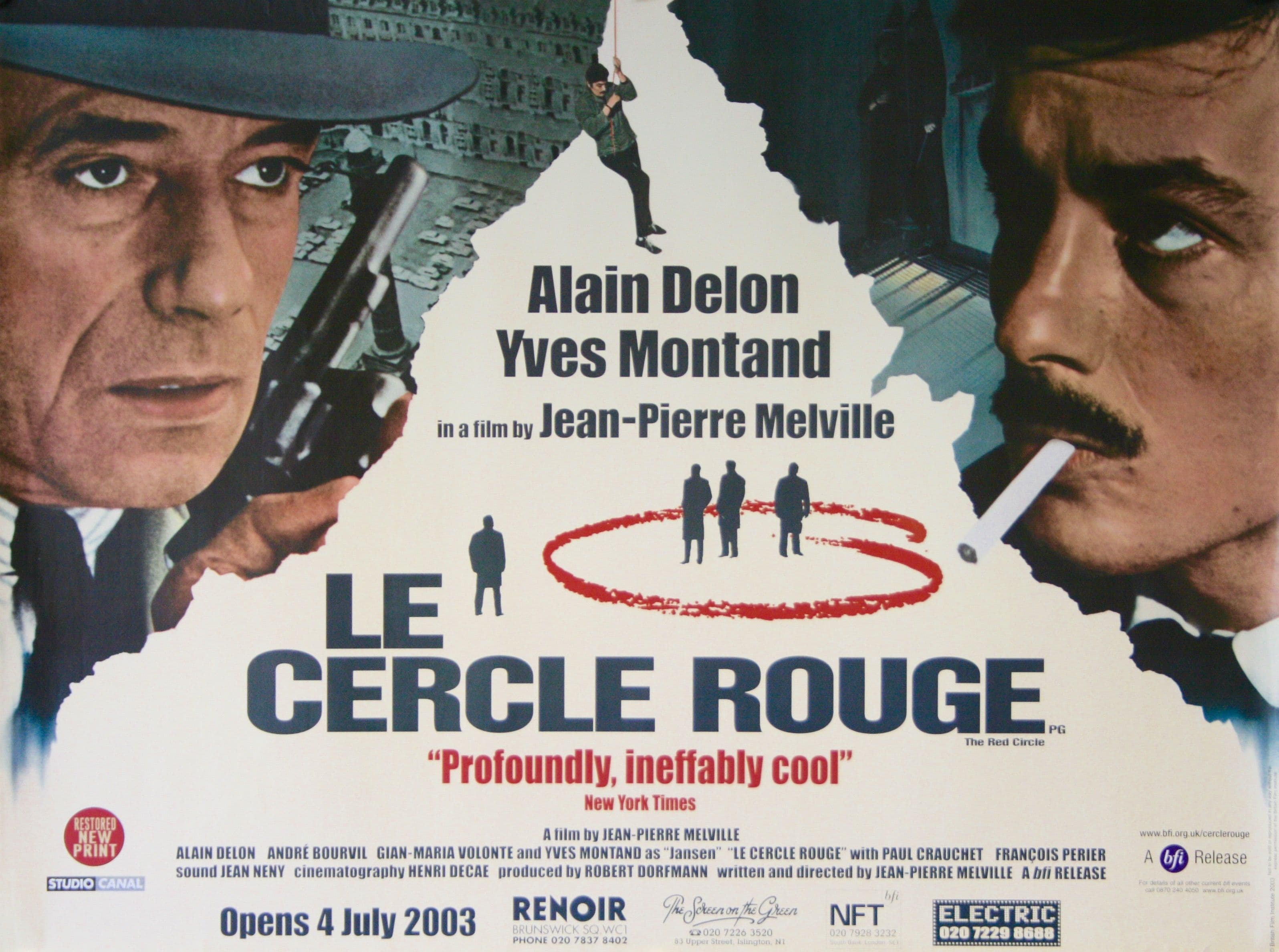

In this regard, note the masterful scene in which Alain Delon – Corey, the elegant professional newly released from prison – crosses paths with Gian Maria Volonté – Vogel, the fugitive with a wild soul. The approach of the two is not a mere fortuitous encounter, but a dance of hesitation and mistrust, where one breathes a kind of dystonia, a palpable cacophony even before a sound is emitted. It is a confrontation between two worlds, two distinct energies, one glacial and controlled, the other volcanic and unpredictable, destined to collide but also to interpenetrate. Melville constructs this moment with relentless direction, made of eloquent close-ups and camera movements that capture every nuance of suspicion and potential alliance. The very air is dense with an almost tangible tension, foretelling a bond that transcends mere convenience.

Then, with an almost ritualistic slowness, the two slowly touch, sense each other, recognize each other. They come to know each other, not through idle chatter or formal introductions, but through a tacit understanding, an affinity of purpose and solitude that unites them in a profound, almost sacred friendship, one that requires no words. This is the hallmark of Melville's cinema: relationships are forged in silence and in the mutual understanding of a code of honor that few chosen ones comprehend. It is here that the theme of the "red circle" emerges, evoked by the cryptic opening epigraph that tells of an invisible circle binding men destined to meet, beyond all logic or will. A karmic bond, almost, that transforms destiny into a complex choreography, a dance of invisible puppets where the strings are woven by fate.

That fusion of souls, observed with the master's clinical eye, represents a pinnacle of cinema, where suspense derives not so much from action as from anticipation, from the palpable tension that precedes the explosion, an almost Bressonian waiting in its ascetic rigor and metronomic precision.

The story proceeds with almost documentary accuracy, following the parallel and then convergent lives of these three men – to whom is added the poignant retired inspector Jansen, played by an Yves Montand in a state of grace, a redeemed alcoholic whose dissolved rationality manifests in an ever-oblique gaze laden with melancholy. The heist plan is never rushed, but takes shape with almost obsessive meticulousness, a ritualistic preparation that is itself an integral part of the spectacle. Melville immerses us in a world of procedures and details, from the procurement of tools to the mapping of spaces, transforming the planning into a symphony of precise and silent gestures, almost a mechanical ballet, until the fateful moment action must be taken. This preparation phase, which occupies a significant segment of the film, is a masterpiece of editing and rhythm, highlighting the professionalism and dedication of the protagonists, regardless of their morality, reflecting the same almost maniacal precision that Melville applied on set.

What emerges is an enchanting film, permeated by a suspended and fatalistic atmosphere, the work of a filmmaker sensitive to the emotion of randomness, to how it regulates lives and decides the fate of men. But in Melville, randomness is often just a mask for a destiny already written, an inevitability that permeates every shot, almost suggesting a predefined cosmogony. It is no coincidence that many critics have likened his style to the rigor of American film noir, of which Melville was a devoted admirer, or to the almost samurai solemnity of certain Akira Kurosawa dramas, where honor and precision of gesture transcend all moral contingency. In "I Senza Nome," each character is a cog in a larger mechanism, a pawn moved by invisible but inexorable forces, and their downfall is never the result of a trivial error, but the inevitable conclusion of a preordained path. The robbery, in this context, is not just a criminal act, but a performance, almost a rite of passage in a world where the boundaries between good and evil are fluid and irrelevant, and where the only true law is that of loyalty and one's own, intimate, consistency.

In this delicate balance between action and contemplation, the three performers are simply superb, true pillars upon which the entire narrative scaffolding rests. Alain Delon, in the role of Corey, is a monument of glacial magnetism, whose sculpted beauty masks a profound melancholy and an almost Buddhist resignation. His silences are more eloquent than a thousand dialogues, and every movement of his is calculated, precise, emanating an aura of dignity that makes the criminal almost tragic. Gian Maria Volonté, on the other hand, delivers a performance of rare intensity in the role of Vogel, embodying a lucid madness that is as visceral as it is controlled, a primal force that moves on the fringes of civilization, yet always within its own, ironclad code. And then there is Yves Montand, the ex-policeman Jansen, whose marked face and whose rationality dissolved into an ever-oblique gaze render a moving and tragic portrait of a man balanced on the abyss, a figure of redemption and despair who acts as a bridge between the two worlds. But one cannot fail to mention the performance of André Bourvil as Commissioner Mattei, the methodical and disillusioned policeman, whose role is not that of a one-dimensional antagonist, but of a melancholic counterpart, also part of that inexorable circle, driven by his own sense of duty and a solitude mirroring that of the criminals he pursues. "I Senza Nome" is not just a genre film, but an elegy on the human condition, an essay on solitude and brotherhood, a timeless work that continues to resonate for its rigorous beauty and intellectual depth, a masterpiece that confirms Melville as one of the greatest visionaries of modern cinema, capable of elevating the polar to pure philosophical art.

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...