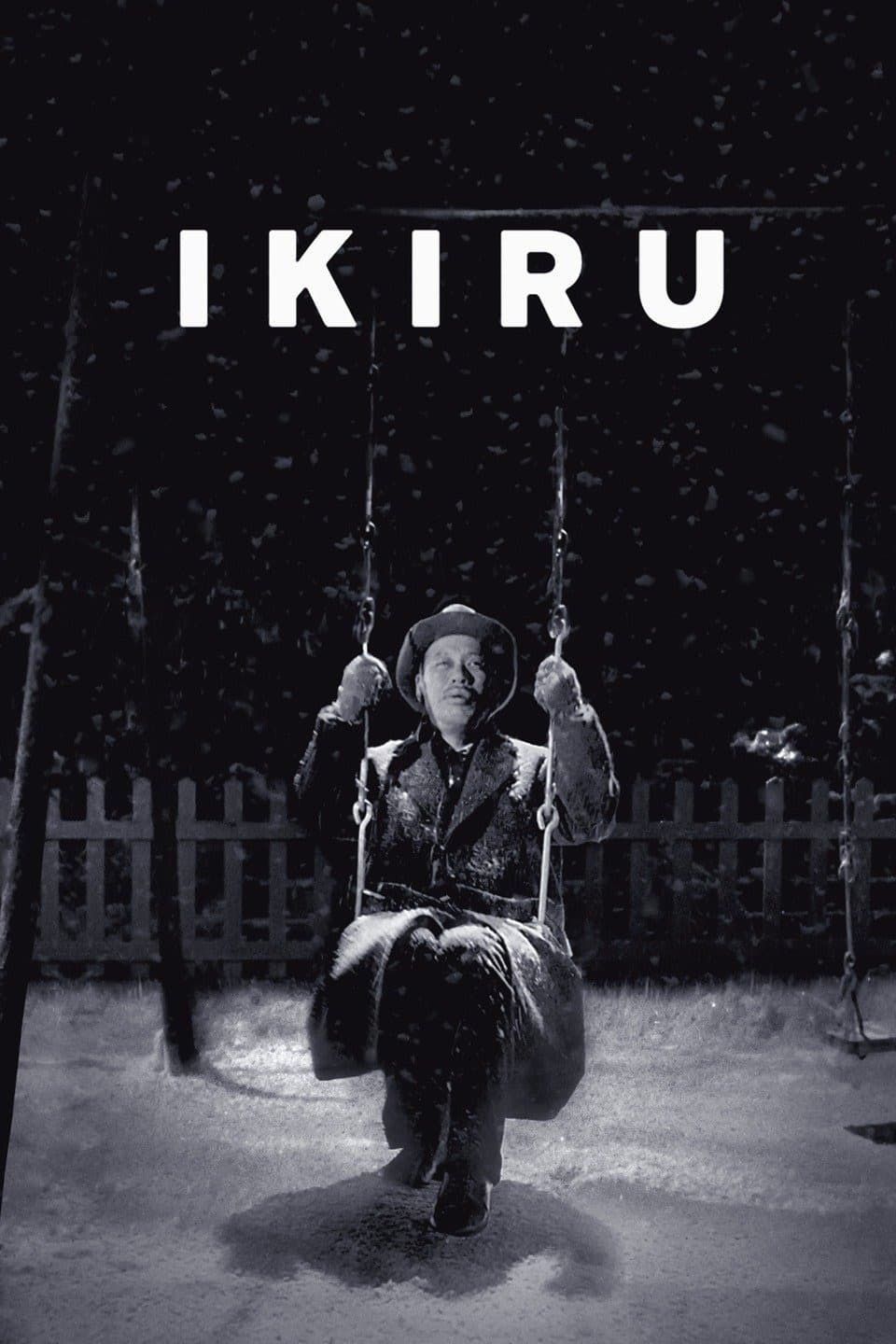

Ikiru

1952

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Often, when one thinks of Akira Kurosawa, the mind races to the clang of swords, the epic tales of samurai, and the dust and mud of monumental battles. Yet his purest and perhaps most universal masterpiece is a film of almost deafening quiet, a work that replaces the katana with a diagnosis of stomach cancer and the battlefield with the dusty corridors of a Tokyo bureaucratic office. Ikiru (To Live, 1952) is an unusually intimate film for Kurosawa, a heartbreaking and deeply human portrait that focuses on a great character, Kanji Watanabe, and his melancholic, belated view of the world as he reaches the end of his life. It is a work that fights the greatest battle of all: the battle to make sense of an existence before it is too late.

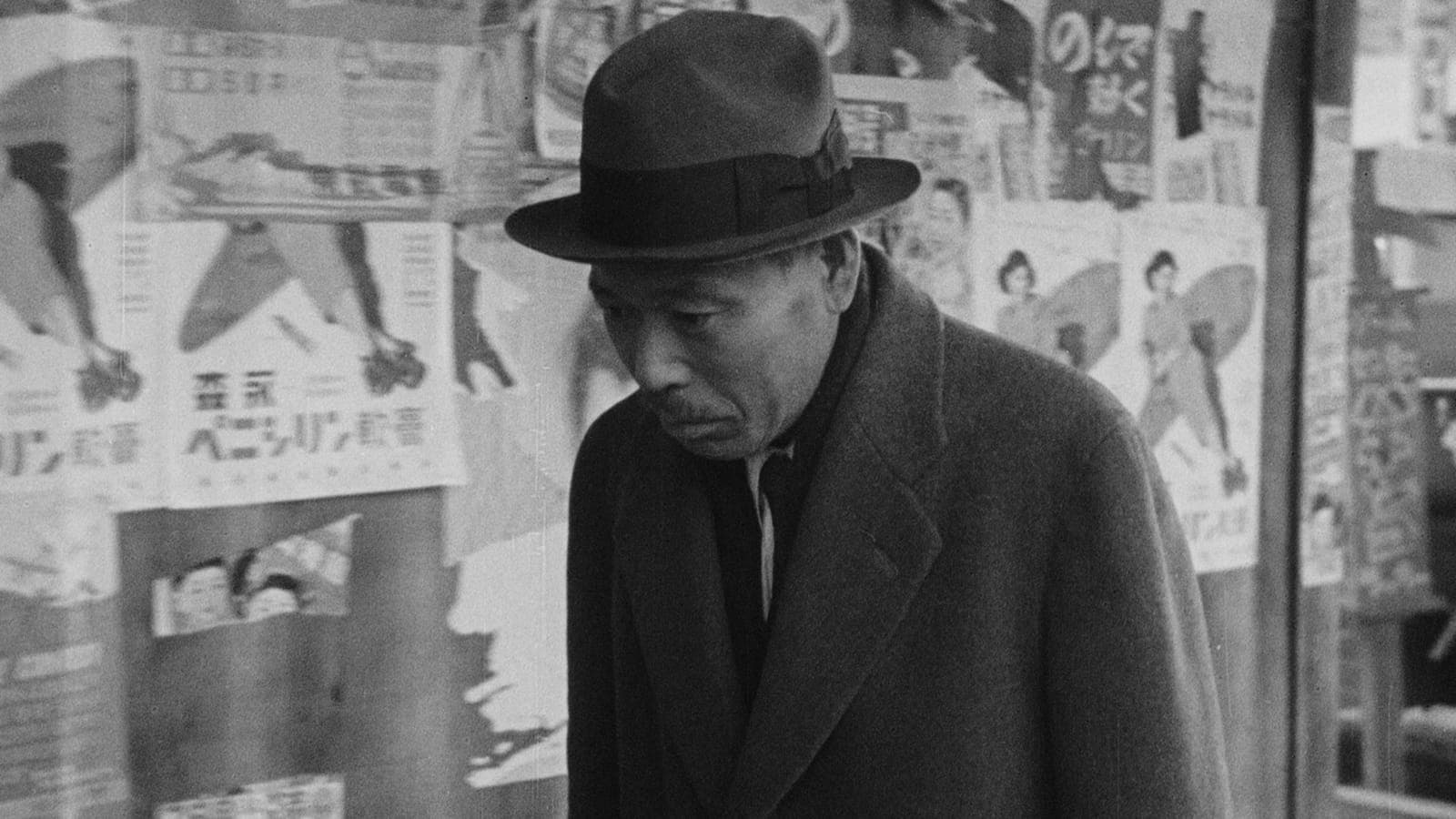

Ikiru can be read as the ontological manifesto of Kurosawa's poetics, a precious film to be savored because it contains, in distilled form, his entire philosophy on the human condition. Its greatness lies in its bold and ingenious narrative structure. For the first two-thirds, we follow the desperate odyssey of Watanabe (an immense Takashi Shimura, whose face is a mask of tragedy and hope), a bureaucrat who for thirty years has been a living “mummy,” stamping papers and saying no to citizens. When he discovers he has only a few months to live, his world collapses. But two-thirds of the way through the film, the protagonist dies. Kurosawa makes a radical gesture here: he dedicates the last, powerful part of the film to Watanabe's wake. Through the fragmented, drunken, and often contradictory memories of his fellow bureaucrats, we try to reconstruct the mystery of his final transformation. The film thus becomes an investigation into memory and the meaning of life, demonstrating that the value of an existence does not lie in how it is lived, but in how it is remembered and in the impact, however small, it has on others.

Kurosawa's existentialism emerges as an aesthetic means of redemption from a certain type of cinema that clearly constrained him. Freed from the codes of jidaigeki, the director immerses himself in a profoundly modern crisis that has more to do with Sartre than with Bushidō. Watanabe, thrown into the world with the awareness of his imminent demise, experiences classic existential escapism. First, he experiences hedonistic nihilism during a Dante-esque night spent in bars and pachinko parlors, guided by a Mephistophelean writer. Then, he attempts to absorb the vitality of others through his fascination with a young and lively colleague, Toyo. However, he realizes that both paths are illusions. True redemption cannot be found outside oneself but must be constructed. His epiphany is an act of pure will: existence precedes essence. He decides to give meaning to his life by performing a single, small, stubborn act: fighting against his own bureaucracy to transform a polluted area into a children's playground. It is not a heroic gesture on an epic scale, but it is his masterpiece, the act that defines and saves him.

The film, while deeply Japanese in its portrayal of postwar bureaucracy—a metaphor for the spiritual paralysis of a nation—is charged with a disconcerting universality, thanks in part to its cultured literary references. It is impossible not to see in Watanabe's odyssey an echo of great Russian literature. His descent into hell in the Tokyo night has a Dostoevskian flavor, but the most powerful and direct parallel is with Leo Tolstoy's The Death of Ivan Ilyich. Both works tell the story of a bureaucrat who has lived an “artificial,” “inauthentic” life and who, only when faced with illness and imminent death, awakens to the terrible realization that he has never truly lived. Watanabe's struggle to build the park is his desperate attempt to perform the one ‘authentic’ act that can redeem an entire existence of emptiness. Although Japanese cinema at the time was populated by other giants, Kurosawa stands out here. While Ozu gently and melancholically analyzed the slow dissolution of the traditional family and Mizoguchi staged the tragic fate of individuals crushed by social structures, Kurosawa infuses his story with a spark of active hope, a powerful affirmation of the individual's ability to act and create meaning for themselves, even within the most suffocating system.

The final scene is one of the most iconic and moving images in the history of cinema. Watanabe, alone at night in the park he created, slowly swings on a swing as the snow falls, singing softly to himself an old melancholic song, “Gondola no Uta.” It is not an image of a sad death. It is an image of triumph. At that moment, Watanabe is fully, totally, painfully alive. He has found his place in the world, he has accomplished his work, and he can leave in peace. Ikiru is a film that every human being should see, a memento mori that reminds us not so much that we must die, but that, precisely because of this, we have a duty and an opportunity to learn how to live.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...