Giant

1956

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(2 votes)

Director

George Stevens, after directing Shane in '53, did not merely sign off on one of the most monumental works of Hollywood's golden age, but sculpted a genuine epic of the American dream, a dense and layered fresco that captured the spirit of an era of transition. If Shane had sealed the frontier with the dust and melancholy of the sunset of Western myths, Giant cast its gaze towards the intoxicating and at times corrupt future of industrialization and oil wealth, rooting itself deeply in the Texan imagination. It is a narrative transition that reveals Stevens' acumen in decoding the evolution of national identity.

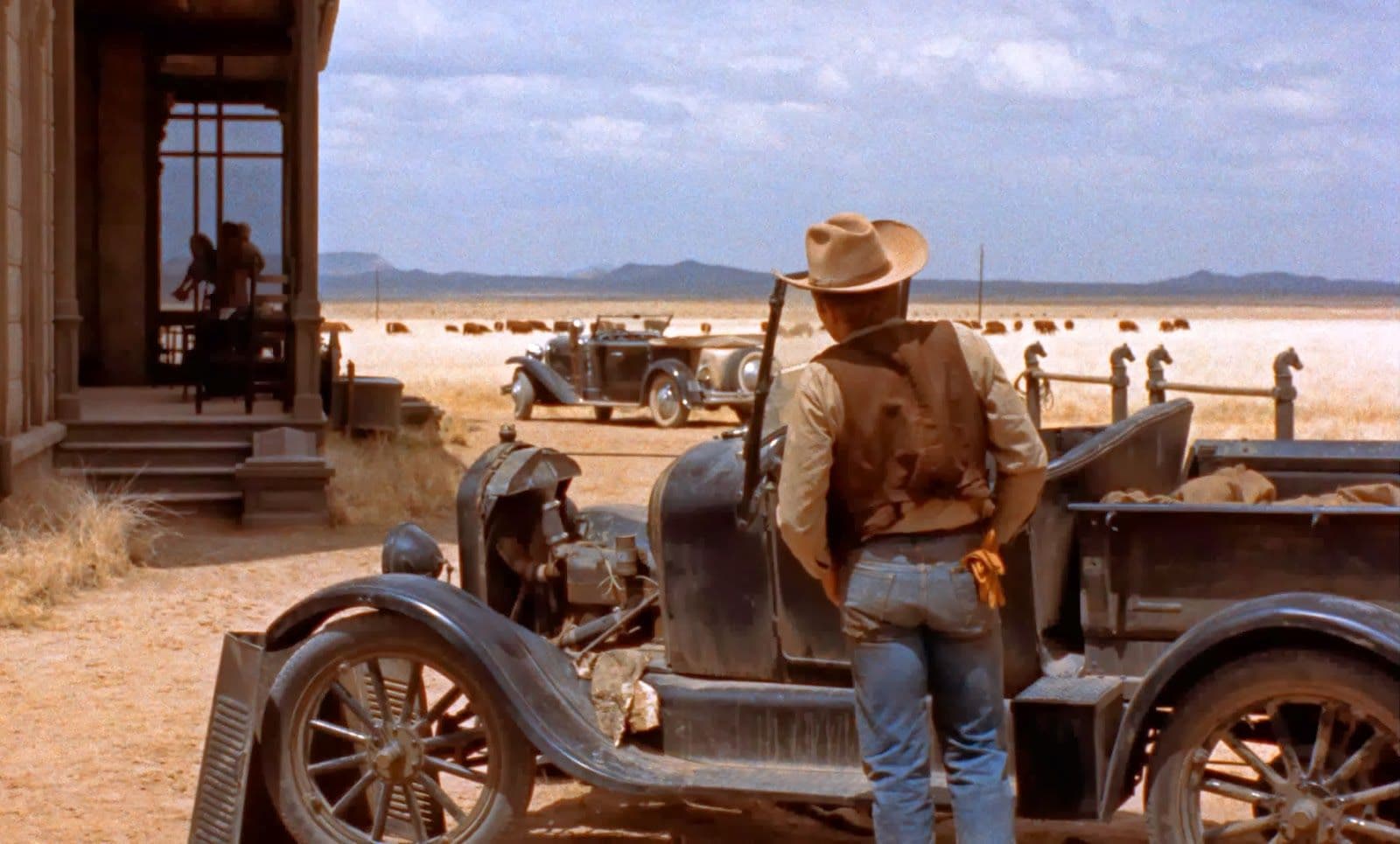

Based on Edna Ferber's eponymous novel, an author whose pen often captured the essence of American family sagas and social transformations – one thinks of Show Boat or Cimarron, both also successfully adapted to the big screen – Giant was immediately a literary success that cried out for its cinematic adaptation. A film with a titanic runtime of 210 minutes that required three years of production, a production odyssey that saw the crew and cast face the rigors of West Texas, specifically in Marfa, where the wind and isolation formed the backdrop for an almost mystical experience for all involved. Its length, in particular, raised concerns at Warner Bros., which asked Stevens to create a shorter version for fear of audience rejection, a request naturally rebuffed. This resistance of the director to commercial pressures is emblematic of his stature as an auteur within the studio system, a man who had the vision and authority to defend it, convinced that every shot and every line was indispensable for the complexity of his fresco.

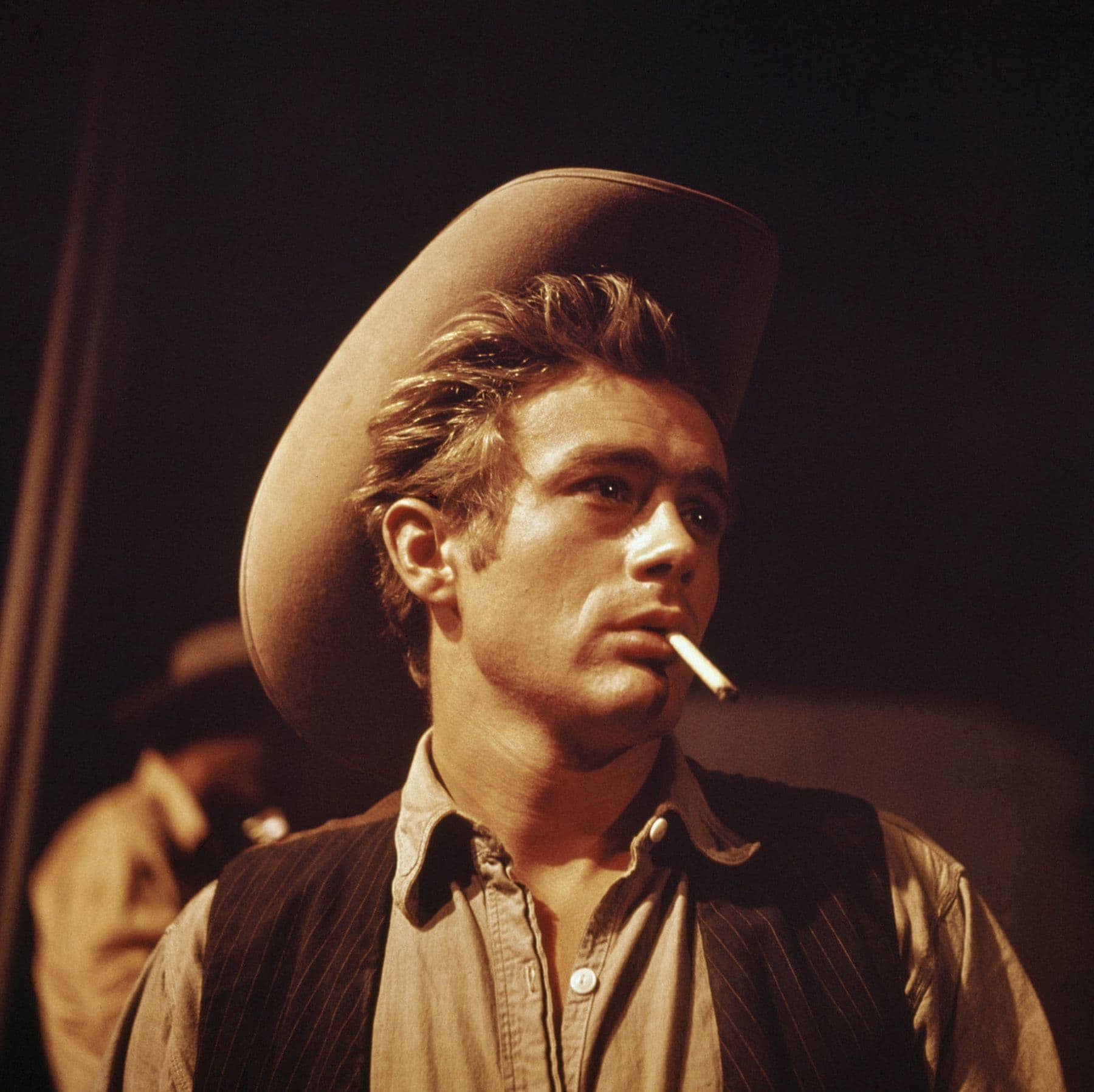

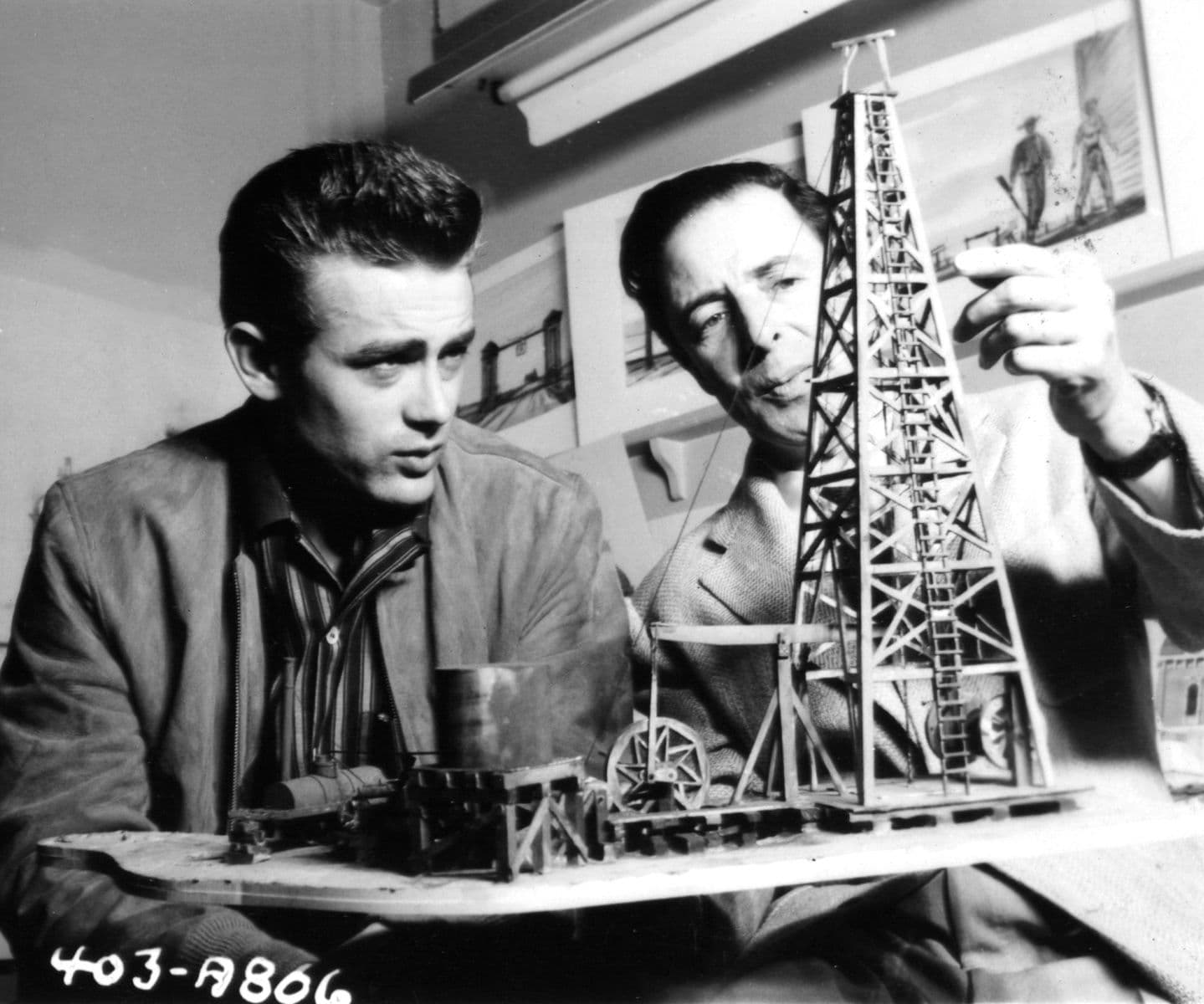

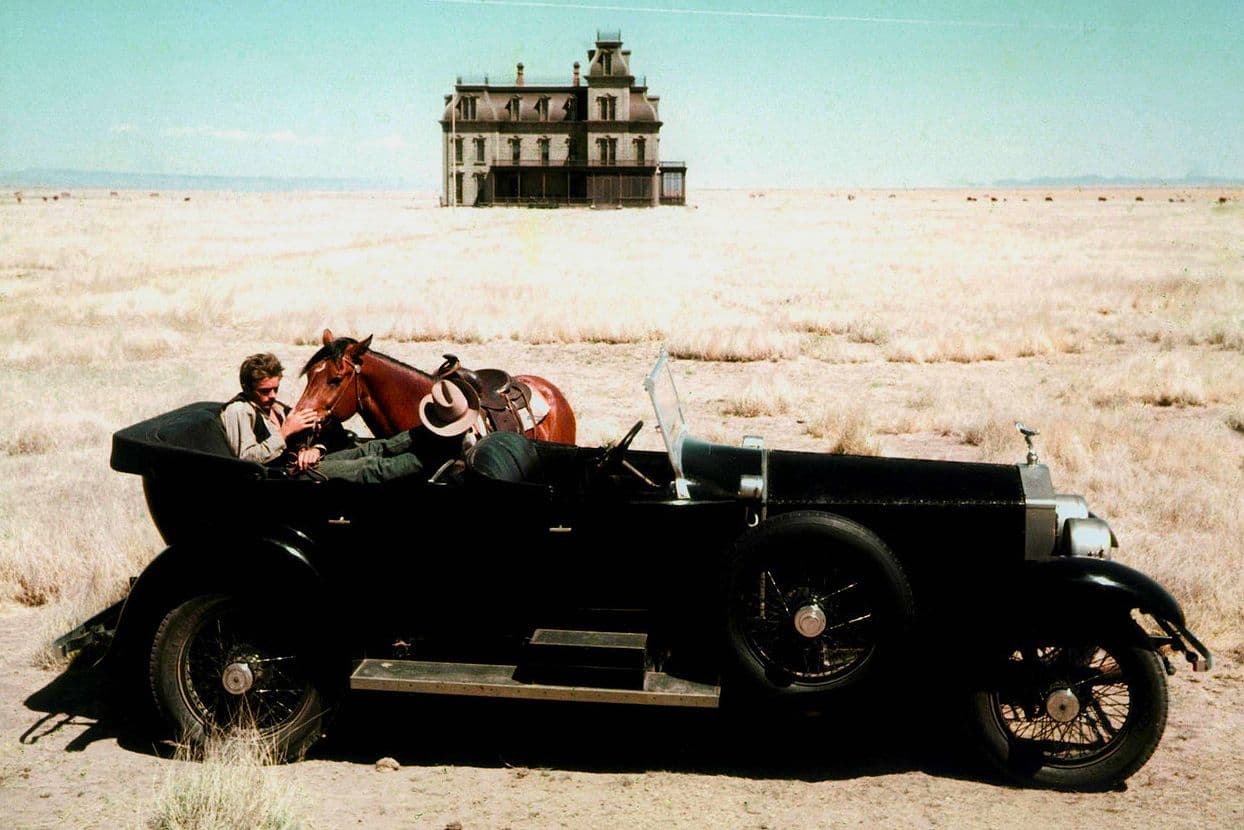

Giant is essentially an epic centered on a Texas family saga, a microcosm reflecting the tensions and metamorphoses of an entire nation. Jordan "Bick" Benedict Jr. (portrayed by Rock Hudson in a state of grace) is the head of the family, the embodiment of the old land-owning aristocracy, tied to the land and its age-old traditions. He has married the wealthy and sophisticated Leslie Lynnton (a sublime Elizabeth Taylor), a woman from Maryland who, with her progressive sensibility, acts as a catalyst for change and a critical mirror of Texan customs, from racial segregation to gender expectations. The peaceful, albeit complex, coexistence of the two will be undermined by the ambitious and resentful Jett Rink (James Dean), a taciturn and rebellious ranch hand who, thanks to a small land inheritance and a stroke of luck with oil, will make an exorbitant fortune and take his cynical revenge on the Benedict family, embodying the dark and predatory side of the American dream. His upward trajectory, marked by an insatiable desire for recognition and an unquenched bitterness, becomes the tragic counterpoint to the (at times naive) nobility of the Benedicts.

The three principal actors are masterful, truly screen titans who offer unforgettable portrayals here. Rock Hudson, in particular, delivered one of his best performances in this film, escaping the clichés of the "leading man" to bring to life a layered character, stubborn yet vulnerable, who credibly evolves over decades, facing the decline of his influence and the emergence of new realities. Elizabeth Taylor, far beyond her iconic beauty, instills Leslie with remarkable intellectual and moral strength, transforming her from a mere wife into a true protagonist of social change within the family and community. But it is James Dean who leaves an indelible mark in his last cinematic performance. His premature death, which occurred shortly after the end of filming (necessitating some voice re-recordings to complete his character), confers on Jett Rink an almost prophetic aura of self-destructive genius. Dean channels his tormented "method" energy into a portrait of rare intensity, a figure of rebellion and solitude who has imprinted himself on the collective imagination like few others.

George Stevens successfully navigates the fine line that divides formulaic melodrama from epic drama, a precarious balance he masterfully maintains for all 210 minutes of the film's runtime. His dramatic pacing, patient yet taut, makes it one of the few epics of its era that continues to withstand the test of time; his vision indeed remains captivating even today. The narrative, though vast and rich in subplots, never loses sight of its thematic cornerstones: progress at the expense of tradition, the difficult coexistence between different cultures and social classes, female emancipation, and the fight against racial prejudice (particularly courageous for cinema of that era). In this, Giant stands as a spiritual sibling to other great American sagas like Gone with the Wind, but with a more disillusioned and critical eye on the distortions of the American dream. William C. Mellor's "bewitching cinematography" contributes decisively to this grandeur, capturing the breathtaking vastness of the Texan landscape, the endless skies and boundless plains that become a metaphor for the grandeur and solitude of the characters, reflecting their unbridled ambitions and intimate fragilities. The wide, almost pictorial shots lend the film a scope that transcends family melodrama to touch universal chords on the human condition and the unstoppable flow of history.

Giant demands time and dedication, certainly, but it repays with a taut narrative and cinematography that is pure visual poetry, offering a cinematic experience that is simultaneously an intimate psychological exploration and a monumental essay on the complex American soul of the 20th century. It is a film that does not merely tell a story, but invites the viewer to reflect on the cost of progress, the ephemeral nature of wealth, and the persistence of values that, even when tested, define the very essence of humanity. A masterpiece that, even today, resonates with surprising modernity.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...