Apur Sansar

1959

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

After Pather Panchali (Song of the Little Road) and Aparajito (The Unvanquished), “The World of Apu” is the third film in the celebrated Apu saga by Indian (Bengali-born) director Satyajit Ray.

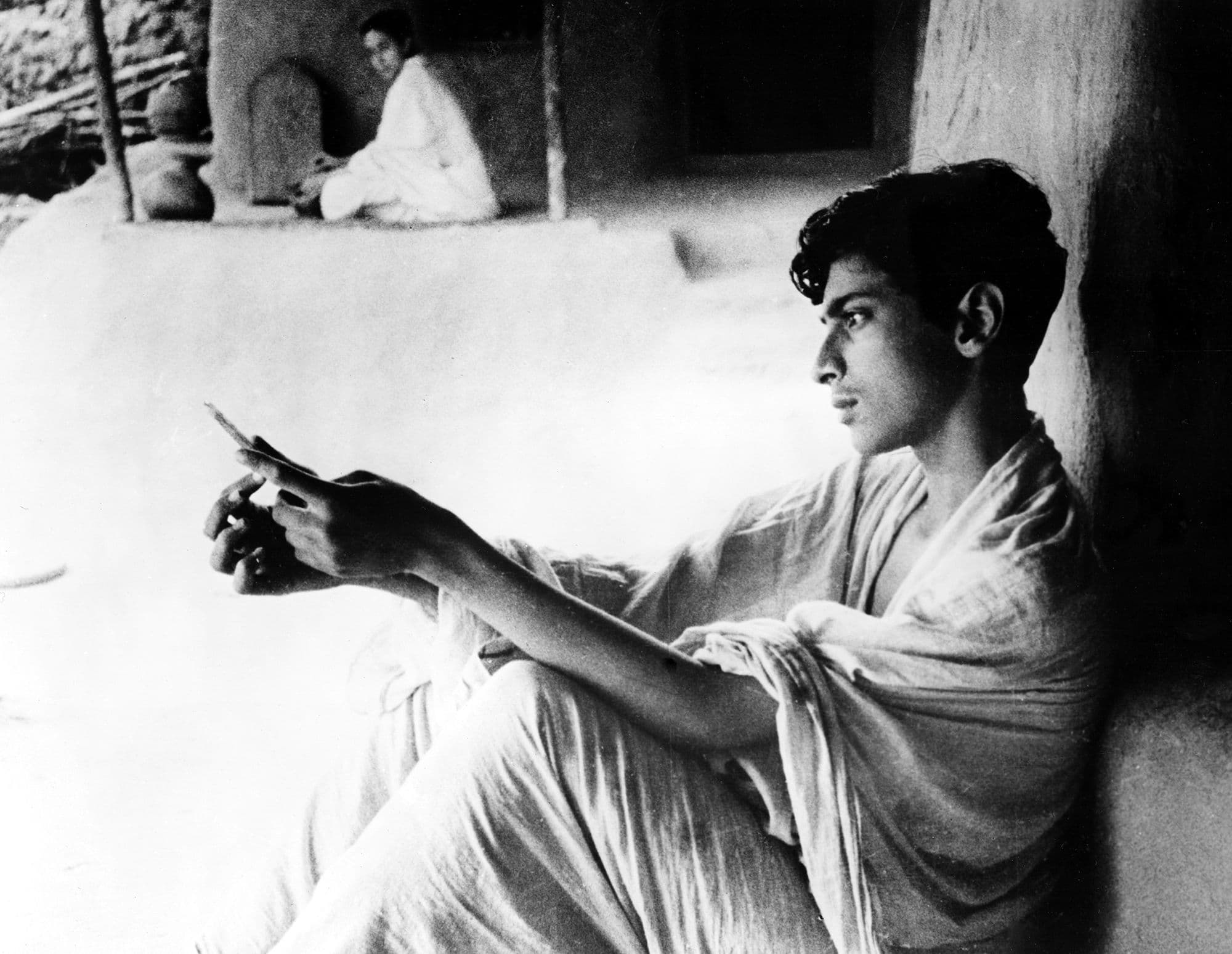

Perhaps of the three, it is the most Western in the psychological drives of its protagonist, certainly the most captivating. This "Westernness" is not a mere stylistic choice, but rather a profound exploration of human archetypes that transcend rural Bengal to reach a universal dimension. Apu, here, is no longer just the boy who grew up among kash fields and secular rites; he is the uprooted intellectual, the budding artist grappling with disillusionment and the search for meaning in a world that seems to reject him. His is an existential crisis that could well inhabit the pages of a Dostoevsky or the canvases of a Hopper, a sensitive soul crushed by the weight of expectations and the fragility of happiness. It is precisely this vulnerability, this incessant search for an identity beyond social conventions, that makes Apu an eternally modern character, a bridge between Eastern spirituality and the anxieties of contemporary man.

The story is that of Apu, a destitute unemployed writer, who marries the beautiful Aparna. The sudden marriage to the radiant Aparna, portrayed by a very young and unforgettable Sharmila Tagore in her screen debut, is the linchpin of a brief but dazzling period of happiness. Their union, born from an act of altruism rather than pre-existing love, blossoms into a palpable chemistry, imbued with an almost ephemeral tenderness, like a dream destined to fade. And fade it does, with the unprecedented brutality of Aparna's death during childbirth, an event that is not just a tragedy, but an inner cataclysm for Apu. His despair is not screamed, but rather creeps in, festers, transforming into a total negation, a pathological refusal of his son who is, in his eyes, the living personification of pain, the unwitting cause of his immeasurable loss. The woman dies in childbirth giving birth to his son, and Apu will refuse to see the child until he is five years old. This self-imposed exile from paternal affection is the beating heart of the drama, an open wound that Satyajit Ray explores with a psychological delicacy reminiscent of Bergman or Truffaut in their exploration of family dynamics and unresolved trauma.

A poignant relationship between father and son will emerge, becoming the focal point of the narrative. The path leading to the reunion with young Kajal (whose name means "kohl," black eye makeup, often associated with protection and beauty in children's eyes, a non-random detail) is an initiatory journey for Apu. It is not a simple rapprochement, but an arduous ascent from the depths of self-pity and emotional reclusion. Ray, with his inimitable direction, shows us the gradual thawing of Apu's heart, the initial awkward interactions and then, little by little, the emergence of a pure bond, untainted by conventions, but forged in mutual necessity. The son becomes the anchor, the catalyst for rebirth, the bridge that reconnects Apu to life, to responsibility and, ultimately, to the hope of a future. This relationship, woven with eloquent silences, fleeting glances, and small gestures of affection, is the true apotheosis of the film, a testament to the resilience of the human spirit and the redemptive power of filial love.

A film of unparalleled stylistic sophistication, where expressionism and neorealism merge to create a work of poignant beauty. And here, Ray's genius manifests in its full maturity. His "unparalleled stylistic sophistication" is not a mere exercise in style, but the weaving of a cinematic language that absorbs and reflects Apu's inner turmoil and the surrounding reality. Neorealism, borrowed from the great Italian lesson of Rossellini and De Sica, manifests in the meticulous attention to daily details, in the use of often non-professional actors (like the very young Alok Chakraborty as Kajal, whose spontaneity is disarming), in the choice to shoot in authentic locations that pulsate with a life of their own, from the crowded alleys of Calcutta to the rural spaces of a return to origins. But superimposed on this adherence to reality, in a sublime counterpoint, is a discreet yet powerful expressionism. The evocative use of shadows, the compositions that isolate Apu in his solitude, the close-ups that delve into the depths of his tormented gaze – every shot, a result of the virtuosity of cinematographer Subrata Mitra, contributes to painting a dense and complex emotional landscape. It is not the visual exasperation of the German masters, but a subtle stylization that amplifies sensations: the claustrophobia of his writer's room, the desolate immensity of the landscapes that reflect his inner void after loss, the light that progressively rekindles in his eyes as the bond with Kajal strengthens. It is this fusion, this harmony between social observation and psychological inquiry, that elevates the film to a universal masterpiece. Ravi Shankar's soundtrack, ethereal and melancholic, weaves another layer of meaning, an ancestral lament that accompanies ephemeral joys and deep sorrows. The film is not just a story, but a complete sensory experience, a visual and emotional symphony.

A film that lingers in the heart, yes, but does much more: it delves into the soul. “The World of Apu” masterfully concludes a trilogy that is not just the story of one man, but the epic of an entire nation in transformation, a bridge between tradition and modernity, between the innocence of childhood and the complexity of adulthood. It is a testament to cinema's ability to transcend cultural and linguistic barriers, to touch universal chords with rare grace and depth. Ray, with this work, does not just offer us a film; he gifts us a mirror in which to reflect our own losses, our own rebirths, and the perpetual search for meaning in life's inexhaustible cycle. It is a work that, with the passage of years, does not cease to reveal new nuances, confirming its status as a cornerstone not only of Indian cinema, but of world cinematic art.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...