Into the Wild

2007

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

“The essence of the human spirit lies in new experiences,” Chris yells to Ron from the top of a ridge; it is a parting remark and Chris is urging his elderly friend to leave a house full of solitude to lose himself in the world, to enact a radical change in his life. It is not just a farewell, but a manifesto, the echo of an existential creed resonating through the breathtaking landscapes of the wildest America. In these words of Chris lies the key to understanding this film: his candor, his overwhelming enthusiasm, his naive joy in discovering the world is the narrative core around which Sean Penn builds a story of freedom from all social constraints, masterfully and sensitively adapting his narrative to John Krakauer's novel of the same name.

Penn, a director of rare emotional intelligence, does not merely faithfully transpose Krakauer's journalistic inquiry, but elevates it to a visual epic, imbued with a lyrical melancholy and an intense spiritual quest. His approach is that of a painter who paints with light and sound, relying on Eric Gautier's sublime cinematography to capture nature's implacable and seductive vastness, and on Eddie Vedder's evocative soundtrack, which becomes almost McCandless's inner voice, a rock anthem to the yearning for purity and youthful restlessness.

Chris McCandless could be one of the millions of young Americans who, after a brilliant college career, is destined for an affluent life and an easy, perpetually downhill path, a preordained journey that embodies the quintessence of the American Dream in its most materialistic manifestation. Yet the young man, in a gesture of radical disillusionment that echoes the disaffection of the 1960s countercultures while placing itself in a contemporary context, donates all his possessions to charity, destroys his credit cards, rents a car, and sets off across the vast American continent, abandoning his name and identity to be reborn as "Alexander Supertramp."

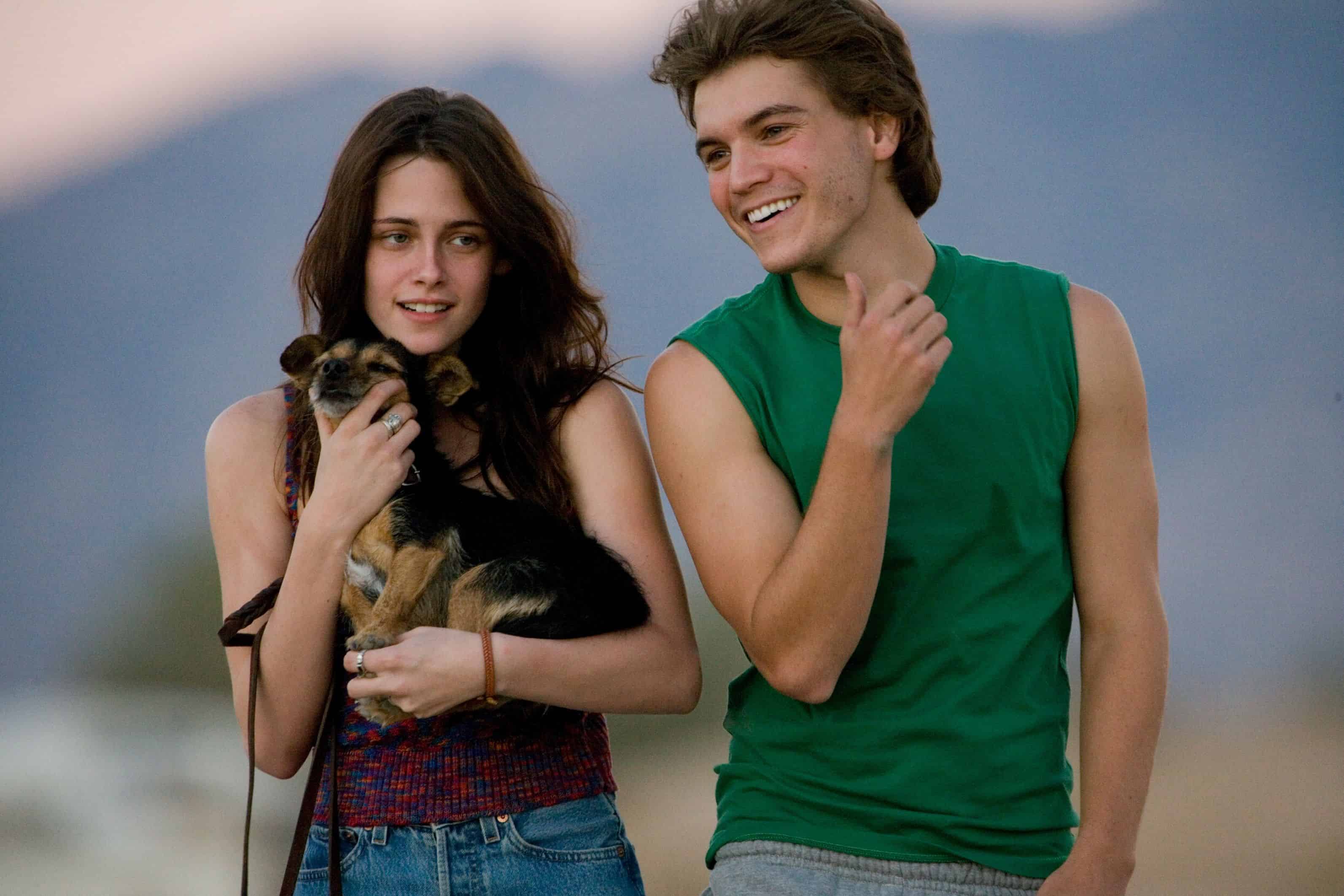

This initiatory journey allows him to savor the very essence of the concept of freedom, the nectar of emancipation from every burden with which society intended to shackle him: the burden of family expectations, conformism, consumerism that atrophies the spirit. It is a path that brings him into contact with a gallery of unforgettable characters, true archetypes of the most marginal yet authentic America. He will meet men and women with whom he shares a piece of his journey, passing like a lightning bolt through their lives and leaving a sense of purity, of a surreptitious affection for his carefree nomadism, almost a catalyst that pushes them to reflect on their own existences. From the hippie couple Jan and Rainey, who find in him a kind of spiritual son, to the rough but golden-hearted Wayne Westerberg, to the elderly and solitary Ron Franz, each encounter is a piece that completes the mosaic of humanity and solitude, and that shows Chris's ability to inspire, even in his flight, a sense of profound connection. His fleeting presence illuminates them, challenges them, forces them to look beyond the horizon of the everyday.

The essence of the film is captured by Lord Byron's verses used as an epigraph at the beginning of the film: "There is a pleasure in the pathless woods, There is a rapture on the lonely shore, There is society, where none intrudes, By the deep Sea, and music in its roar: I love not Man the less, but Nature more." This passage is not a mere quote, but a hermeneutic key that reveals the pulsating heart of the narrative: the quest for a primordial, almost transcendental authenticity, in communion with the wild element. The film, in this sense, engages in dialogue with a long American literary and philosophical tradition, from Emerson to Thoreau, from Whitman to Kerouac's beatniks, all driven by a discontent with civilization and an irresistible attraction to the road and to nature as the only true teacher. Alaska, the final destination of his pilgrimage, is not just a geographical destination, but the embodiment of that "ultimate limit" where life and death confront each other without filters, where man strips himself of every superstructure to reveal his true essence.

Emile Hirsch, in portraying McCandless, offers a performance of extraordinary physical and psychological dedication, embodying with equal force his visionary innocence and his sometimes blind obstinacy. His body, which progressively transforms on screen, becomes a metaphor for sacrifice and extreme vulnerability in the face of an unforgiving environment. It is a film that shakes us to the core, allowing us to glimpse what each of us might have become had we decided to surrender to the wild element, to heed that ancestral call that promises absolute freedom but that, inevitably, demands a price. The narrative, enriched by the brief but powerful incursions of the voice-over by his sister Carine McCandless (Jena Malone), adds a dimension of tenderness and suffering, reminding us of the pain left by his radical choice. A tragically fatal freedom for Chris's body, consumed by hunger and the implacable nature, certainly not for his soul, which finds peace precisely in the ultimate embrace with the wild he had so sought and loved. His story is not only a warning about the dangers of excess, but an ode to the courage of living with authentic passion, a hymn to the search for a meaning that transcends conventions and continues to inspire, even at the cost of life.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...