Annie Hall

1977

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

A neurotic, ironic, and irrational film, Woody Allen’s Annie Hall sees the director unleash all his creativity, bringing to life a character who lays bare the workings of his own mind, his obsessions, his emotions, to reverberate them onto the viewer, who follows him always with a half-smile ready to turn into a boisterous laugh. Alvy Singer, the alter ego of an Allen at the height of his creative powers, is not simply a character, but a true archetype: the Jewish-New Yorker intellectual, perpetually in analysis, obsessed with death, sex, politics, and, above all, women. His neurosis is not a flaw, but the very driving force of his comedy and his inescapable humanity, making him a man with whom it is impossible not to empathize, even when his self-irony borders on the purest self-flagellation.

The result is an enjoyable work, where each of us steps into Alvy Singer’s shoes and shares his deepest neuroses, laughing at the barrage of his witty lines (some of the best: “Hey, don't knock masturbation: it's sex with someone I love,” “My grandmother never gave me any presents, she was too busy being raped by Cossacks,” “Politicians have their own ethics. All their own. And it's one notch below that of a sex maniac”). These quotes are not mere boutades, but flashes of genius that illuminate Alvy’s cynical and disenchanted view of the world, a view that, despite its eccentricity, reflects the anxieties and absurdities of modernity. Allen’s genius lies in his ability to transform human misery into sublime comedy, a rare alchemy that elevates the genre to heights of psychological and social introspection.

The story is a gigantic flashback where the protagonist relives his life, his phobias, and above all, his love for Annie, an aspiring singer trying to achieve success. But the narrative of Annie Hall is far from linear or conventional. Allen masterfully breaks the fourth wall with ease, addressing the viewer directly, inserting subtitles that reveal the characters' unexpressed thoughts, Disney-style animations, and even fragments of a childhood evoked with a wry glance. This fragmentation and incessant meta-cinematic dialogue are not mere stylistic devices, but the very hallmark of Alvy’s disquiet, his need to analyze, deconstruct, and understand an existence that eludes him. The influence of the French Nouvelle Vague, particularly Godard with his anti-narrative approach and his break with conventions, is palpable and is re-elaborated in a quintessentially Allenesque style, transforming formal innovation into a vehicle for psychological exploration.

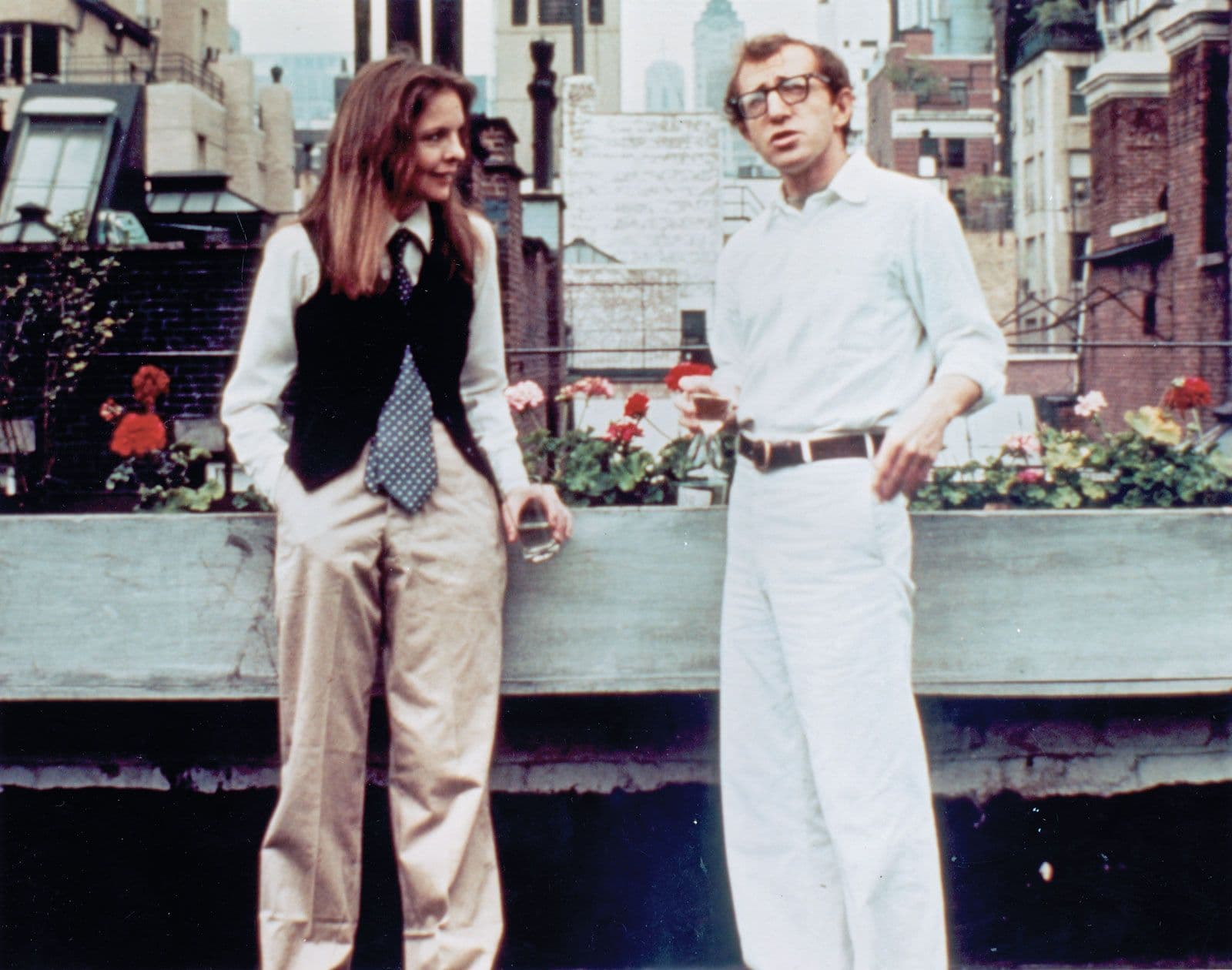

We follow its break-ups and reconciliations, its scenes and quirky, self-ironic declarations of love, until it reaches where no lover has gone before. The relationship between Alvy and Annie (masterfully played by Diane Keaton, whose sartorial style in the film – men's blazers, vests, ties – generated a true fashion revolution, the famous "Annie Hall look") is the pulsating heart of the film, a merciless but affectionate autopsy of how love can blossom between two such dissimilar personalities and, inevitably, wither. Annie, with her disarming spontaneity, her fragility, and her search for an artistic identity, is the antithesis to Alvy: while he is a prisoner of his New York intellectual neuroses, she aspires to liberation and success, even if it means embracing the superficiality of the West Coast. The conflict between New York's neurotic intellectualism and Los Angeles's lightheartedness (or vacuity, depending on one's perspective) here becomes a metaphor for Alvy's internal struggle between his mind and his heart, between what he thinks and what he desires. It is a film that dissects relationship failure not as tragedy, but as an inevitable consequence of two life trajectories that, despite having crossed paths with passion, were destined to diverge.

Some scenes are truly hilarious, like the killing of the spider in Annie's bathroom at three in the morning amidst a thousand questions, hesitations, and "whys," a small domestic tragedy elevated to a parody of male anxiety. Or the scene of the cinema queue with the pedantic critic behind him who expounds upon his hermeneutic doubt about Fellini's latest work (for the record, it should be Casanova) while Alvy wishes he could cover him in horse manure. It is in moments like these that the film reveals its satirical genius. Then, at the umpteenth harangue from the annoying guy against Marshall McLuhan, Alvy erupts and turns to the camera, moving from reality to "what if": and so he literally pulls Marshall McLuhan himself out of a billboard, who destroys the guy to Alvy's immense glee. This scene, in particular, is a masterpiece of meta-narration and intellectual satire, a brilliant exemplification of Allen's ability to play with narrative conventions and to ridicule the pretentiousness of the academic world, transforming a daily frustration into an explosion of surreal satisfaction. It is the triumph of fantasy over dullness, of intellectual vivacity over sterile pedantry.

Annie Hall is not just a romantic comedy, but a profound exploration into contemporary identity, existential anxieties, and the ephemeral nature of human bonds. Its genesis was far from linear: initially conceived as a dark thriller titled "Anhedonia," it gradually transformed under the pen of Allen and co-screenwriter Marshall Brickman into what critic Vincent Canby defined as a "comedy of ideas," a rare gem that unites the lightness of laughter with the depth of philosophical reflection. It redefined the "romantic comedy" genre, stripping it of excessive sentimentality to infuse it with a massive dose of realism, self-irony, and acute psychological observation, paving the way for countless imitations.

A wonderfully rich film, full of playful sarcasm and authentic inspiration, the same inspiration that Allen would soon rediscover in another of his masterpieces, Manhattan, with which Annie Hall forms an indispensable dyad in the director's cinematic pantheon. A film that not only won Oscars for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actress, and Best Original Screenplay, but that continues to resonate, forty years later, with surprising freshness and relevance, demonstrating that the truest art is that which, while starting from the particular, manages to grasp the universal.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...