I'm Still Here

2024

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

With this film by Walter Salles, we are faced with a work of almost unimaginable complexity and delicacy, a political thriller that slowly dissolves into a poem about memory, an investigation into the brutality of history that turns into a meditation on the fragility of consciousness.

The great Brazilian director has created his most ambitious and heart-wrenching masterpiece, a work about memory and the trauma experienced by an entire nation. The narrative moves between two time frames and, apparently, two distinct stories, which turn out to be fragments of a single, broken soul.

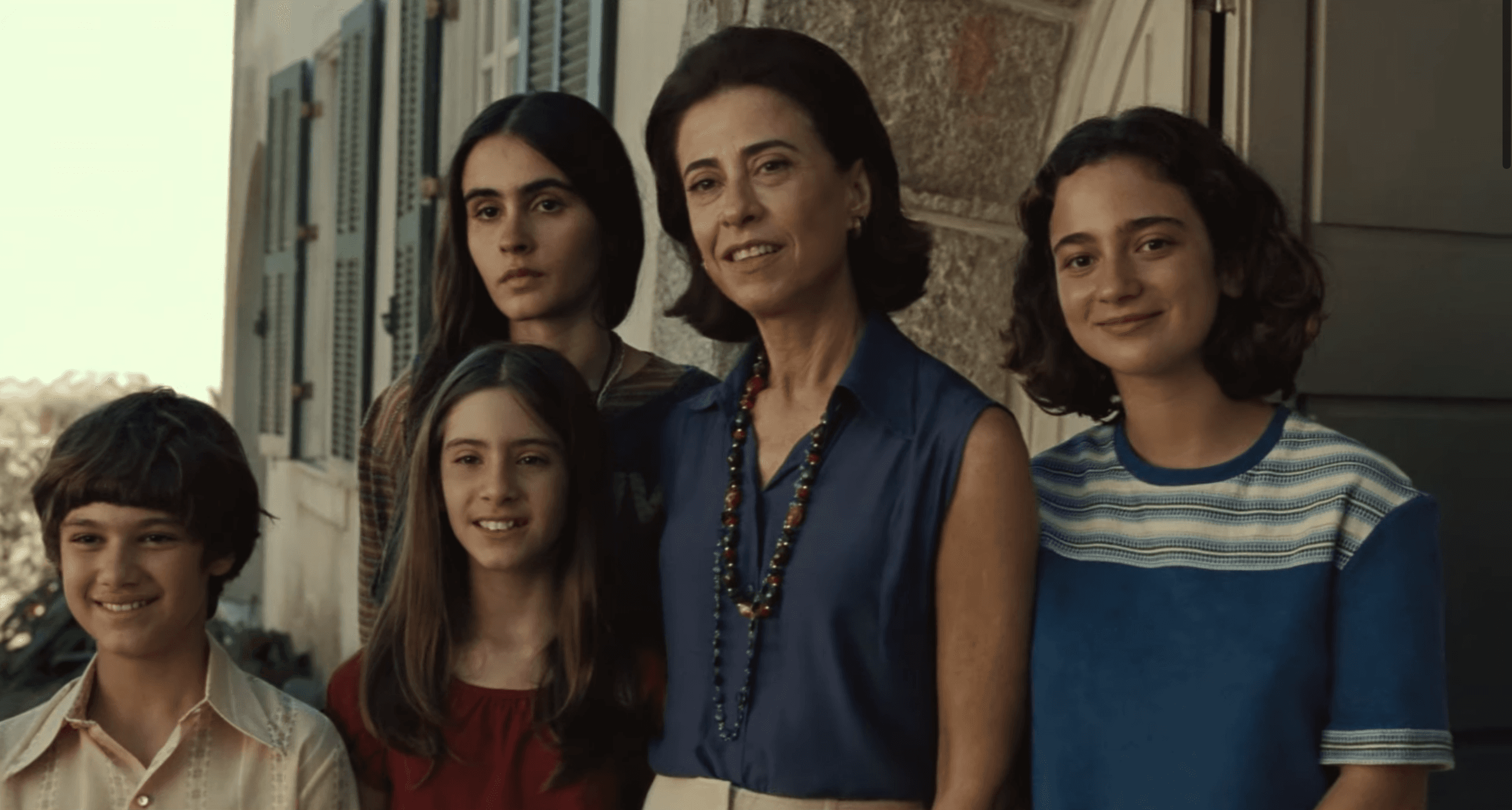

We begin in Brazil in 1971: a country in the increasingly tight grip of a military dictatorship. The life of Eunice, a young teacher, and her husband, a dissident painter, is destroyed by an arbitrary act of state violence: he is taken away by the military and becomes one of the many desaparecidos. From this moment on, Eunice is forced to reinvent her life; from wife and intellectual, she becomes a silent and stubborn pasionaria of memory, a woman who spends the rest of her life fighting to prevent her husband's memory from fading into the oblivion imposed by the regime.

Then, with an ellipsis as abrupt as it is poetic, the film transports us decades later to another dimension. Here, the work becomes a phenomenological investigation into the dissolution of consciousness, the portrait of an elderly European painter struggling against the advance of Alzheimer's to complete his last self-portrait. And here, the viewer begins to understand the film's ingenious and moving game: this second story is not a parallel story. It is Eunice's inner world. Elderly and afflicted with dementia, her mind, in a desperate attempt to cling to the memory of her painter husband, has merged her memory with the imaginary biography of a European artist they both admired. Her personal trauma has been poured into an artistic archetype.

This second level of the film is a work of austere, almost sculptural beauty. The photography is clearly inspired by the portraits of late Rembrandt: the light seems to emerge from the darkness, illuminating the dust in the air, the texture of the canvas, the cracks on the protagonist's face. The narrative is not linear, but follows the unpredictable and fragmentary paths of the painter's memory, which are actually fragments of Eunice's memory. He moves between the present, where his hand trembles but his will is iron, and flashbacks, which are not mere memories but actual hallucinations, where figures from the past (the young Eunice, the ghosts of the dictatorship) enter and leave his room like visitors from another time.

The work dialogues beautifully with other great films about old age and memory, but subverts their premises. If Haneke's Amour showed the physical devastation of the end of life with almost clinical lucidity, and Zeller's The Father made us experience the labyrinthine confusion of dementia from within, Salles' film chooses a third way: that of artistic and political resistance. Its protagonist, whether the fictional painter or Eunice who imagines him, uses the act of painting, the only language he has left, as an anchor to prevent himself from being swept away by the tide of oblivion. Every brushstroke is an act of memory, an attempt to say “I am still here.” It is a film of heart-wrenching emotional power, a work perfect in its execution. The title thus takes on a double, powerful meaning: it is the battle cry of the political dissident who refuses to be erased from history, and it is the desperate whisper of a conscience struggling not to vanish into the fog of dementia.

In this way, Salles creates a work that is both a tribute to the Latin American political cinema of the 1960s and 1970s, with its denunciation of dictatorships and the desaparecidos, and a work that fits into the tradition of great European auteur cinema on memory, where historical trauma and personal memory merge. The genius lies in bringing these two worlds together. Eunice's political struggle for her husband's historical memory is transformed, in her old age, into a neurological struggle for her personal memory. The act of remembering becomes the last, supreme act of resistance. The film suggests that forgetting a state crime and forgetting the face of those we love because of illness are two sides of the same terrible tragedy: the loss of identity.

The ending is a moment of indescribable beauty and sadness. We see the elderly Eunice, in a rare moment of lucidity, facing a blank canvas. Her hands, which we saw trembling and uncertain in the body of the imaginary painter, now move with newfound determination. She begins to paint. We do not see the process, but at the end the camera shows us the finished painting: it is not a Rembrandt-style self-portrait, but a vibrant, almost expressionistic portrait of the smiling face of her young husband, as he was in 1971. In that last, heroic act of creation, she has managed to defeat both dictatorship and disease, bringing the truth back to light, if only for a moment. It is proof that art is not only a tool for recounting memory, but is memory itself. For its bold and moving narrative structure, its profound political reflection, and its ability to find heartbreaking beauty at the heart of tragedy, this film manages to move and awaken consciences from the torpor of oblivion. And that is no small feat, no, ultimately it is not at all.

Main Actors

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...