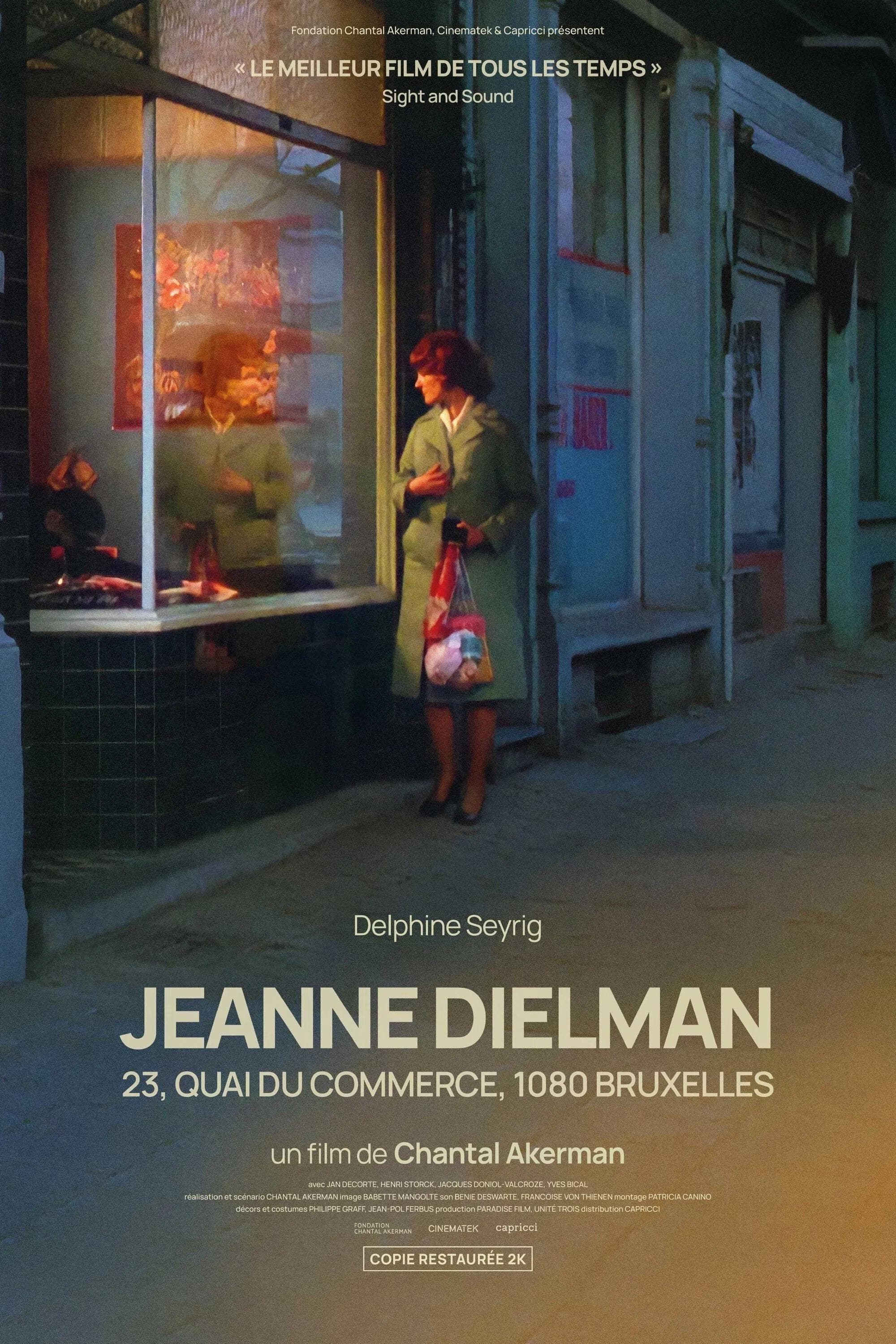

Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles

1975

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Chantal Akerman's monumental 1975 work, shot when the director was only 25, is an act of almost inconceivable audacity and rigor. For three hours and twenty minutes, she asks us to do one thing: watch. Watch a woman make a bed, prepare a meatloaf, polish her son's shoes, peel potatoes. And in this act of patient, almost voyeuristic observation, Akerman constructs one of the most powerful and devastating treatises on the female condition, on alienation and on the latent violence that lurks beneath the surface of bourgeois routine. It is an absolute masterpiece, whose recent coronation as “best film of all time” by international critics is not hyperbole, but the rightful recognition of a work that anticipated decades of conversations about art, feminism, and the language of cinema.

In the hands of Belgian director Chantal Akerman, the drudgery of women's work and prostitution are not so far apart; every rigorous domestic chore performed almost in real time and every paid afternoon appointment we see the protagonist, the widow Jeanne Dielman (a legendary performance by Delphine Seyrig), carry out brings the viewer closer to the inevitable crack in her impeccable facade. The film is both a triumph of structuralist cinema and an extraordinary indictment of gender roles in society. And yes, watching someone peel potatoes for five interminable minutes has never been so compelling, because in that gesture Akerman encapsulates an entire universe of repression and precarious order.

The film is the most radical deconstruction of the concept of Kammerspiel, or chamber drama. The action is confined almost entirely to Jeanne's apartment, a place that transforms from a nest into a prison before our eyes. But it is a Kammerspiel stripped of all critical dialogue. Unlike the dramas of Bergman or Strindberg, here the conflict is not in the words. The dialogues are sparse, functional, almost emotionless. The real drama is in the gestures, in the ritual, and above all, in its imperceptible disintegration. Akerman's camera is almost always static, fixed, positioned at a medium height that observes Jeanne with a clinical, almost scientific distance. She enters and exits the frame, which remains impassive, defining the architectural space of her existence. This aesthetic choice is not accidental. It is an immersion in the minimalist and conceptual art of the 1970s. Like a work by Donald Judd, the film focuses on form, space, and duration.

As in a durational film by Andy Warhol, the act of watching a mundane action for a long time imbues it with a new and profound meaning. It is precisely in this real-time aesthetic that the film caught the attention of critics, who hailed it as one of the most beautiful films of all time. Akerman's most revolutionary choice is to devote the same amount of time and directorial attention to each of Jeanne's actions.

The time she takes to make coffee is the same as the time she takes to receive a client. In this way, she accomplishes a powerful political act: she equates domestic work with sex work. Both are shown as “jobs,” tasks to be performed with mechanical precision and without emotional involvement to ensure economic survival and order in the home. Prostitution is not an act of transgression or passion, but simply another item on her daily agenda, sandwiched between shopping and preparing dinner. This is the film's most radical feminist thesis: the invisible, unpaid work of the housewife and paid sex work are two sides of the same coin, two forms of alienation of the female body in the service of a patriarchal order.

The influence of this film is immense, though often underground. It is a work that paved the way for a whole strand of slow cinema, influencing directors who work with duration and observation, from Gus Van Sant to Kelly Reichardt. If one looks for parallels in Belgian cinema, Akerman remains an almost unique figure, more closely linked to the international avant-garde of New York (where she lived and was influenced by filmmakers such as Michael Snow) than to a specific national school. Her legacy is transversal, and it is that of having demonstrated that political cinema can be made not through explicit content (slogans, speeches), but through form. The real politics of the film lie in its stubborn, revolutionary slowness. It forces us to experience Jeanne's time, her boredom, her oppression.

The film follows three days in Jeanne's life. The first two are a display of perfect control. Everything is in its place, every gesture is calculated. But on the second day, something begins to crack. The potatoes are overcooked. The coffee is bitter. A button pops off. These are small accidents, almost imperceptible, but in such a rigidly ordered universe, every anomaly is a harbinger of catastrophe. On the third day, order collapses. During a meeting with a client, Jeanne experiences an orgasm for the first time. This involuntary act of pleasure is the final crack, the intrusion of chaos and emotion into a ritual that was supposed to be purely mechanical. Her reaction is immediate, cold, and terrifying. She gets dressed, takes a pair of scissors from her work table, and kills the man. It is not a crime of passion. It is an act of restoration. It is a desperate attempt to eliminate the source of disorder, to silence the disturbance that has shattered her world. The long, motionless final shot, with Jeanne sitting at the dining table in the darkness, illuminated by a strip of light, is one of the most indelible images in the history of cinema. It is the portrait of a woman who, in order to preserve the order of her life, had to destroy it. It is a work that cannot be forgotten. Ever.

Genres

Gallery

Featured Videos

Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...