La Haine

1995

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

A great film by Mathieu Kassovitz about youth malaise, an electric shock traversing and riding the seething resentment smoldering in the remote suburbs of the French capital. The discontent, layered by decades of failed policies, broken promises, and an almost colonial state indifference, finds its explosion in a night of unprecedented violence. The film, conceived in the wake of the real urban unrest that set the French banlieues ablaze in the early 90s – particularly the killing of a young man by the police – does not merely register their echo, but dissects their origins and consequences with almost surgical precision.

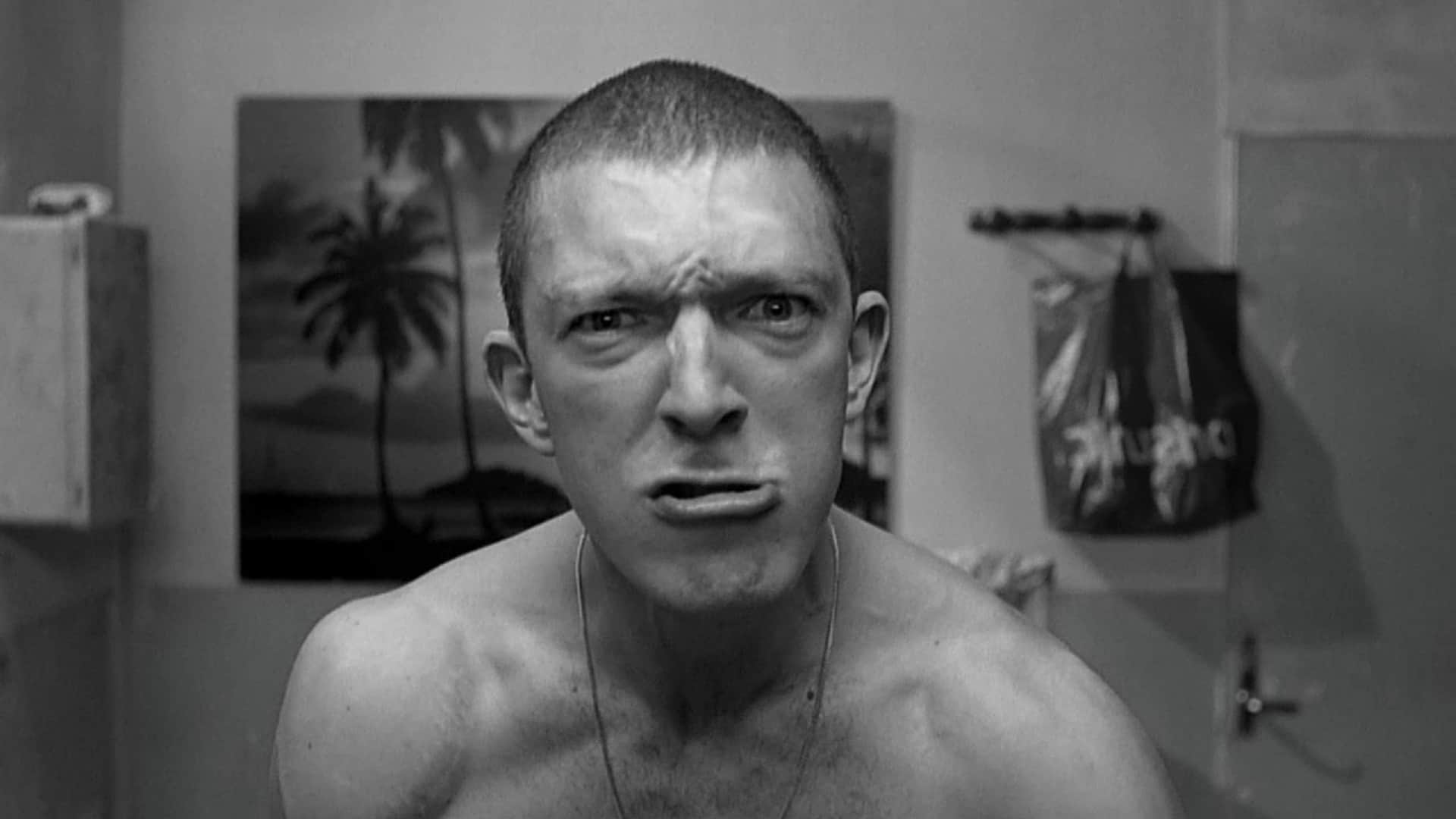

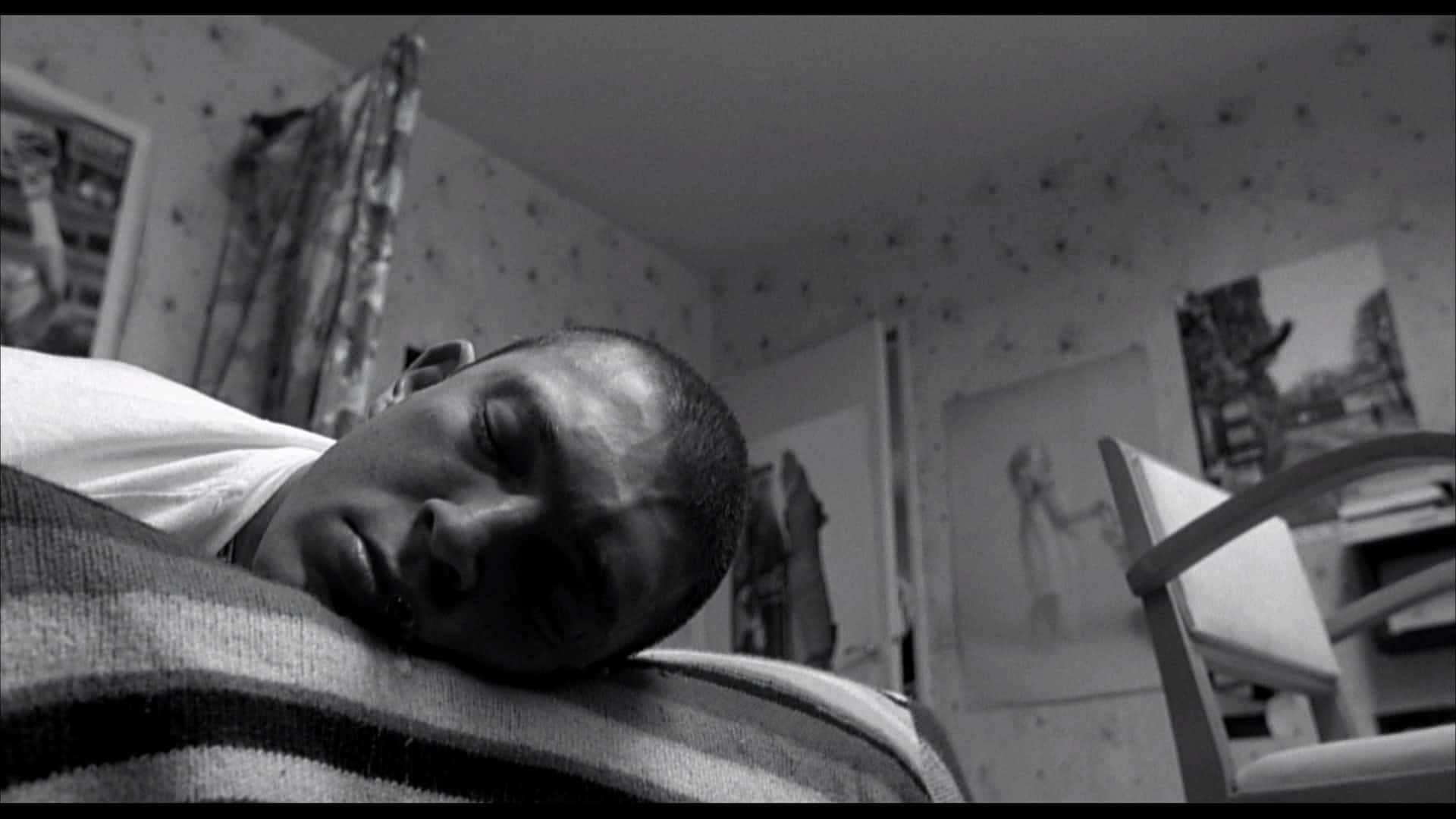

In the aftermath of these violent protests, quashed in blood by the police, a trio of friends, rather than two as the tension would suggest, find themselves navigating the psychological and material rubble of a neighborhood in turmoil. There is Vinz, the impulsive and enraged, portrayed with a feverish intensity by Vincent Cassel – indeed, mentioning Cassel is not only due but almost insufficient, given the whirlwind of emotions he embodies in his main character, a young man torn between vengeful fury and a desperate search for dignity. At his side are Hubert, the philosopher-boxer, the pragmatic individual forced to dream of elsewhere, and Saïd, the cynical and sharp observer, the group's critical conscience. Their pilgrimage through the 24 hours following the clashes becomes an urban odyssey, an inexorable countdown towards an uncertain fate, amplified by the discovery of a police-lost gun, which fuels Vinz's desire for revenge and triggers a tragic mechanism.

The banlieue is not mere background, but a silent and implacable protagonist, in all its social tension; it is a theatre for a story with strong metropolitan connotations, yet devoid of the glittering allure of the city center. Here, the raw, almost neorealist black-and-white cinematography is not a nostalgic aesthetic choice, but an ethical one: it purifies the image of any superficiality, highlights the brutality of architectural lines and the dramatic quality of faces, lending the narrative a timeless universality, almost as if it were a historical document filmed at the precise moment history is made. This stylistic device, which evokes the essentiality of the Nouvelle Vague but with a virulence absent in its more bourgeois manifestations, elevates the narrative from chronicle to urban myth.

Overall, a work that strikes the gut by stirring up the sociological implications of marginalization and maladjustment typical of the banlieue. Kassovitz does not moralize, but shows, with almost documentary precision, the perennial state of suspension in which his characters live, a social limbo from which it seems impossible to escape. The film is a merciless diagnosis of urban pathologies: endemic unemployment, lack of prospects, police brutality, latent and overt racism. These are themes that, unfortunately, have not lost their relevance, making Hate a perpetual warning about the fragility of the social fabric.

The banlieue, then, as a non-place in the sense Marc Augé would give to the term: a transit space, an intersection of paths rather than a hearth of identity. It is the crossroads where multifaceted ethnicities converge – the Maghrebi, the Black, the Jew – in a forced cohabitation that oscillates between street solidarity and internal tensions, men without destiny, unfinished works, marginalized lives struggling in a labyrinth of profound social injustices and racial tensions. Yet, precisely in this non-place, almost paradoxically, a powerful collective feeling of belonging emerges, a street brotherhood that compensates for institutional shortcomings. Famous in this sense is the scene where the improvised DJ blasts music from his apartment window, hip-hop as a lingua franca for a generation, creating a kind of ephemeral cohesion through the glue of the notes. It is a moment of rare poetry, a breath of respite in the daily asphyxia, where art – be it music or graffiti on walls – attempts to transcend misery, to fill the identity void with a vibrant rhythm, ephemeral like the soap bubble of an illusory harmony.

The use of music and language, with the lively slang and caustic wit of the dialogues, elevates the film to a true cultural manifesto of an era. Kassovitz understands that the authentic voice of the banlieue also resides in its underground artistic expressions, in its capacity to generate its own culture, resistant and resilient. In this sense, Hate inscribes itself into a cinematic lineage that includes works like Spike Lee's Do the Right Thing or John Singleton's Boyz n the Hood, films that gave voice to urban minorities, exploring the complexity of their experiences in contexts of violence and discrimination. But Kassovitz does so with an intrinsically French gaze, rooted in post-colonial specificities and betrayed republican rhetoric.

The film closes with a scene of chilling brutality, an epilogue that offers no catharsis but only the bitter taste of inevitability. The famous line "C'est l'histoire d'un homme qui tombe d'un immeuble de 50 étages..." resonates as a self-fulfilling prophecy, a countdown of despair that culminates in the final act of violence. Hate is not a film about hope or individual redemption, but about the perpetual and cyclical nature of violence ("La haine attire la haine"). It is a work that is simultaneously a love for marginality, in its raw and disarming authenticity, and an attempt to transcend its limits, while recognizing the tragic difficulty of doing so. An indispensable masterpiece, whose resonance has not faded, but on the contrary, has grown sharper over the years, testifying to its profound and painful relevance.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...