Night of the Living Dead

1968

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

One of the cornerstones of the horror genre, a work that transcends mere categorization to become a true landmark in the collective imagination. Directed by George A. Romero in a spectral black and white, yet also disturbing in its refined aesthetic implications, "Night of the Living Dead" inaugurated a subgenre from which hordes of screenwriters and directors would draw heavily, never quite achieving the macabre and oppressive atmospheres of the original archetype. The choice of monochrome, far from being a mere budget necessity – though it undoubtedly benefited the meager finances of Image Ten Productions – proved to be an artistic decision of inestimable value. It bestowed upon the film a raw, almost documentary-like authenticity, a hyperbolic realism that amplifies the horror, making it tangible, palpable. This was no longer gothic terror hidden in the shadows of remote castles, but an anguish that emerged from domestic familiarity, from the violation of the everyday. Every shadow is denser, every bloodstain (or what it evokes) more terrifying in the absence of color, evoking the expressionistic suggestions of German cinema or the gloomy atmospheres of American film noir, but reinterpreted with a terrifying modernity.

While certainly not the first zombie-themed film – let us recall that the very first was Victor Halperin's “White Zombie” from 1932, a work imbued with Haitian folklore and voodoo suggestions, where the zombie was a creature subservient to the will of a master – it can nonetheless be affirmed that with this work, the zombie movie gained the status of a subgenre, becoming a specific branch of the Horror genre. Romero divested the zombie of its exotic servitude, liberating it onto the streets and making it an autonomous threat, an embodiment of death itself that walks and infects. This new archetype would have various interpreters in the years to come: from Ed Wood with his eccentricities, to Italian masters of horror like Mario Bava and Lucio Fulci who would amplify its grotesque and visceral aspects, all the way to visionaries like Wes Craven, Sam Raimi, John Carpenter, Peter Jackson, Roger Corman, Danny Boyle, Zack Snyder, Tobe Hooper. All, in their own way, have paid homage to or reinterpreted Romero's legacy, but none have replicated the primordial impact and disconcerting immediacy of his debut.

The plot, in its disarming simplicity, is based on the "resurrection" of the dead in an almost feral form. The creatures roam the world in search of human flesh with which to appease their insatiable hunger, a hunger not only physical but almost metaphysical, an inexorable call to return to dust, to entropy. Every bite generates a contagion that transforms the victim into a zombie, propagating the horror with the speed of a pandemic, a concept that would resonate with unsettling foresight in the decades to come. Some survivors gather in an isolated farmhouse, transformed into a desperate fortress to resist the ravenous hordes. This siege, seemingly one-sided, soon proves to be a double-edged trap.

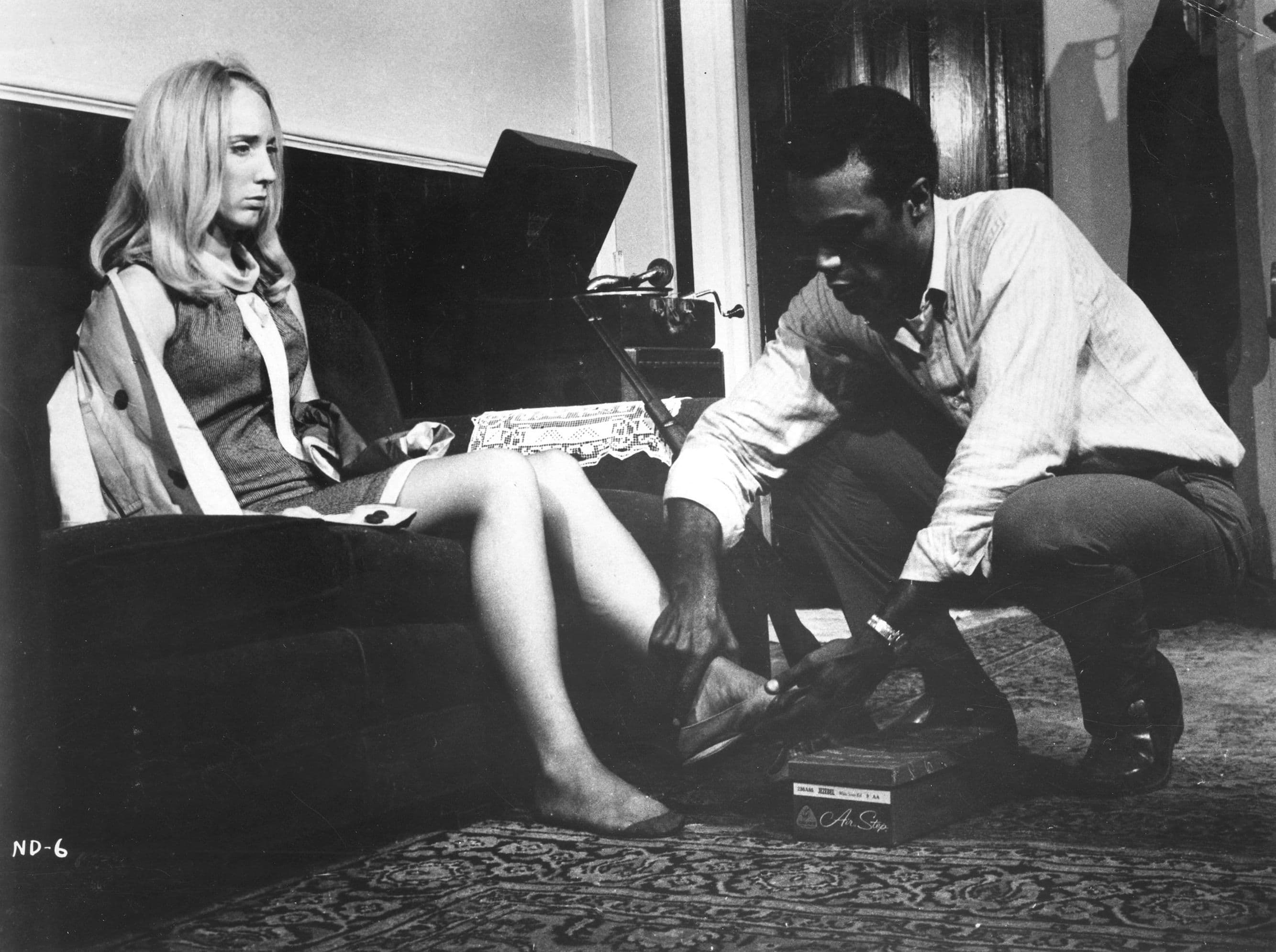

Inside the house, in fact, a microcosm of human relationships is established that, under the pressure of an incomprehensible existential threat, often escalates into open conflicts, into a disintegration of the social fabric which is perhaps the film's most terrifying aspect. In Romero's view, man proves to be the most dangerous predator to his own kind, not out of instinct but due to pettiness, selfishness, and an inability to cooperate. The protagonist Ben, played with restrained dignity by Duane Jones, is a charismatic and rational figure, an African American in an America marked by racial tensions. His leadership is constantly challenged and undermined by the obtuse belligerence of Harry Cooper, an archetype of the patriarchal white man who refuses to relinquish control, symbolizing the deep fractures in American society of the late 1960s. The film, though unintentionally (given that Jones's casting was a pure coincidence of finding a talented and available actor), became a powerful commentary on race relations and the disintegration of authority and trust. This veiled, yet incisive social critique elevates "Night of the Living Dead" beyond a simple horror film, transforming it into a parable about humanity's failures in the face of apocalypse, an allegory of the chaos of the Vietnam War and the civil unrest that was tearing the nation apart.

Many famous scenes are part of our collective terrifying imagination, etched indelibly into collective memory. The scene where the living dead thrust dozens of dangling arms through the gaps of a barricaded door, an image of unsustainable vulnerability and violation, symbolizes the inevitable collapse of security barriers, both physical and psychological. Or the terrible scene where a baby zombie diligently feeds on its own mother, an act that overturns every foundational taboo of civilization – maternal love, the protection of childhood – transforming innocence into abjection, the purest affection into cannibalistic hunger. This moment of pure nihilistic horror, filmed with almost clinical composure, is a punch to the gut that heralds the end of all hope and the advent of an era where moral rules no longer hold any meaning. And finally, the ending, brutal and merciless in its tragic irony, which underscores the absurdity of fate and the futility of all human effort in the face of an indifferent and unstoppable threat. Romero offers no catharsis, only the echo of an unheard cry, leaving the viewer with a sense of profound desolation and the awareness that, perhaps, the greatest monsters reside within us.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...