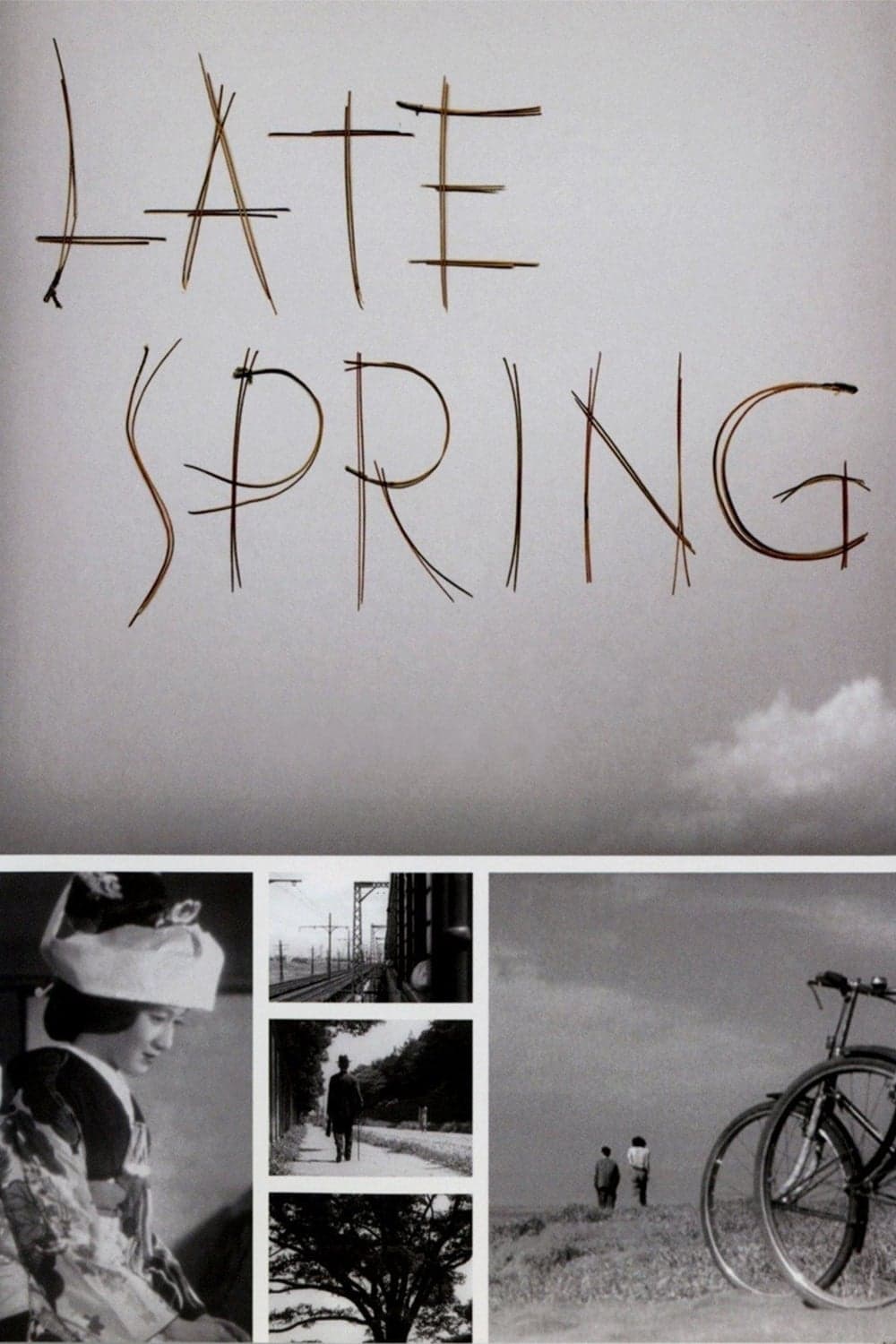

Late Spring

1949

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

A wondrous enchantment where every image is arranged with infinite love and an extraordinary aesthetic sense. This is not a mere stylistic choice, but a true philosophical vision: the camera, often placed at tatami level, invites us to participate in the characters' daily lives, to immerse ourselves in their domestic intimacy, almost as if we were silent guests in a Japan in transition. His celebrated "pillows" (pillow shots), pure transitional shots of inanimate objects or urban landscapes, serve as meditative pauses, as narrative breaths that allow the viewer to assimilate emotions just experienced and prepare for those to come, distilling time into fragments of pure contemplation.

Ozu once again proves to be a refined intellectual, creating a work that reflects the values and traditions of his people not only from a formal but also a semantic perspective. His cinema, despite its apparent simplicity, is a complex inquiry into the human soul and the social changes of post-war Japan. While directors like Kurosawa dedicated themselves to heroic epics or historical dramas and Mizoguchi explored female suffering and social injustices, Ozu chose to remain firmly anchored to the domestic sphere, exploring with keen sensitivity the cracks appearing in the traditional family fabric under the impetus of modernity and Westernization. His works are seismographs of the Japanese soul, recording with almost ethnographic precision the tensions between the giri (duty, social obligation) and the ninjo (personal feeling, desire).

Indeed, in this film, he addresses a theme dear to him: the disintegration of the family and the estrangement of affections. A recurring motif in his filmography – from Tokyo Story to Equinox Flower – which here, in Late Spring, takes on the contours of a bittersweet and poignant elegy, the chronicle of an announced farewell. The generational conflict, the loneliness of elderly parents, the children's difficulty in reconciling personal fulfillment with filial ties: these are universal themes that, through the specific lens of Japanese culture, reach pinnacles of sublime emotion.

The story is that of a widower who lives alone with his daughter, Noriko, portrayed by Setsuko Hara with dazzling and melancholic beauty, whose enigmatic smile became a symbol of an era and a spirituality. The man, Shuhei, played by the faithful Chishū Ryū, wishes for the girl to find a husband and does everything to convince her. But the girl is deeply reluctant to leave her father alone, trapped between her unconditional love for him and the growing social pressure to marry. Their bond, permeated by eloquent silences and an almost symbiotic understanding, is the beating heart of the film, a portrait of devotion that defies conventional logic. The man, aware that only a drastic break can push his daughter towards her future, orchestrates a stratagem imbued with altruism and pain, an act of feigned betrayal to free her from the burden of her devotion. The final scene, with Shuhei slowly peeling an apple, a gesture of quiet solitude after his daughter's departure, is an icon of Ozu's cinema, an epitome of mono no aware, the gentle melancholy for the transience of things and the beauty of their impermanence.

The delicate balance of the elements at play, the velvety cascade of images that washes over us, inundating us with pure beauty, the crystalline style, the gentle unfolding of feelings: all this contributes to making this film an unmissable work. Its apparent slowness is not inaction, but a deep immersion into the characters' psychology, an invitation to patience that translates into a rare emotional richness. The often repetitive conversations, the minimalist acting, everyday gestures elevated to rituals: every element of Ozu's grammar aims to unmask the complexity hidden beneath the surface of ordinary life. It is a cinema that teaches us to listen to silences, to read between the lines of social conventions, to perceive the unsaid that weaves the deepest human relationships. Late Spring is not just a film, but a meditative experience, a life lesson on renunciation and acceptance, on the poignant beauty of letting go and the inevitable cycle of human existence. To establish an oasis of peace and beauty in our frenetic lives.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...