Le Samouraï

1967

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

A highly inspired Melville reconstructs the perfect and sublime solitude of a killer and captures its twilight atmospheres with surgical precision that is at once glacial and deeply touching. His stylistic signature, comprised of long silences, measured gestures, and impeccable visual architecture, elevates the narrative to a level of pure formal abstraction. Every shot is a pictorial composition, permeated by a palette of grays, blues, and blacks that reflects the character's soul and the inevitability of his destiny. Melville does not merely tell a crime story; he paints an existential fresco on predestination and isolation, pushing the concept of the solitary anti-hero to its extreme consequences. In this, the director is clearly indebted to a certain Bressonian rigor, yet combined with a noir aesthetic that evokes the chiaroscuro of Edward Hopper's paintings, with his characters suspended in an eternal urban melancholy.

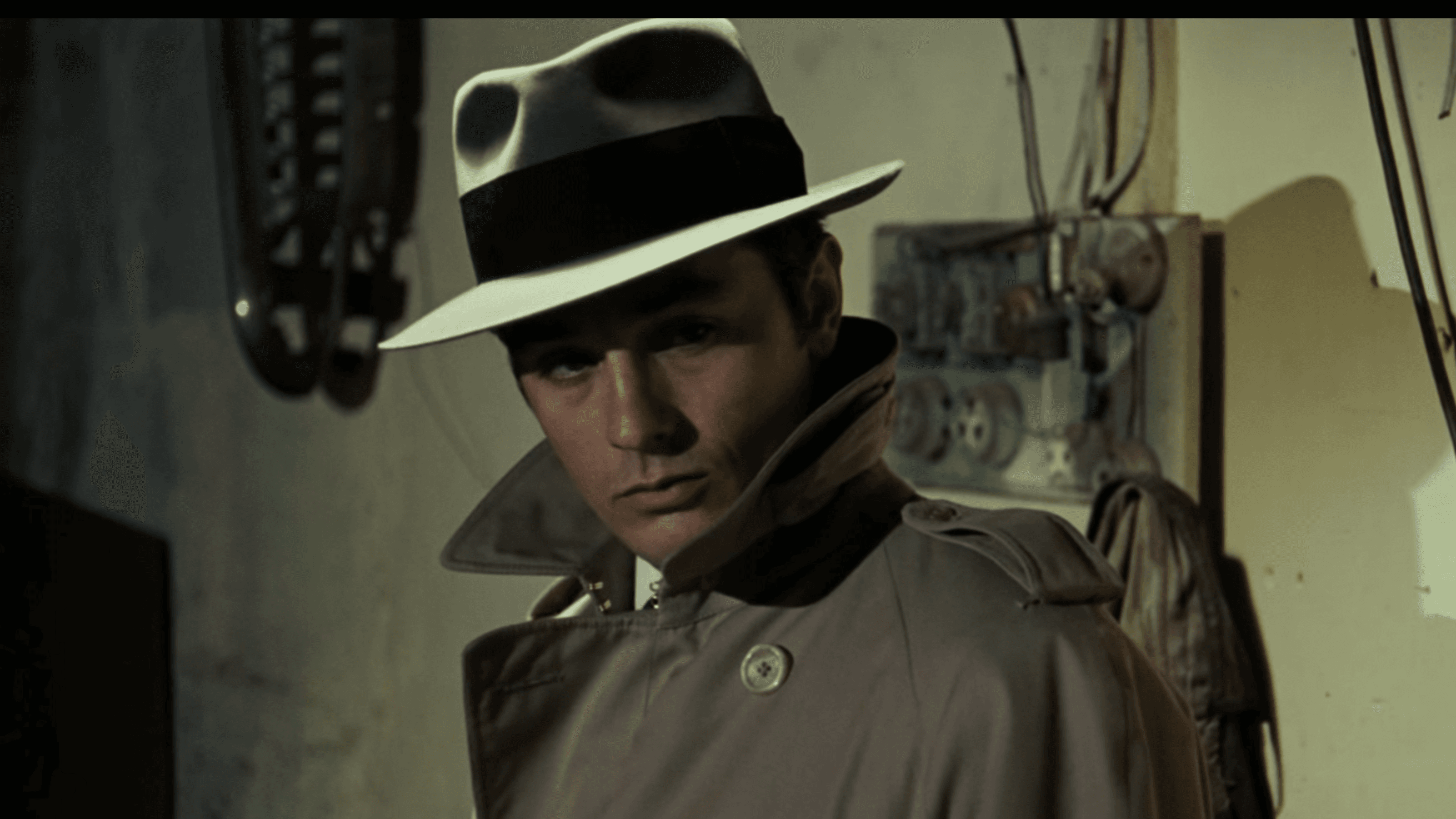

Here, the director is aided by Alain Delon's astounding performance in one of his best roles. Delon doesn't act; he is Frank Costello. His icy beauty, his calibrated inexpressiveness, his penetrating gaze become the perfect vehicle for a character who communicates more through his absence of emotion than with any dialogue. He is a face of stone that hides a tormented soul, an innate elegance that contrasts with the brutality of his profession. His minimalist acting is a tour de force of subtraction, where every tic, every controlled body movement, every imperceptible variation in his gaze reveals layers of psychological complexity. This role would cement Delon's image as an icon of a certain type of cinematic masculinity: cold, detached, fatal, destined to shape the collective imagination and influence generations of actors and directors, from Jean-Pierre Léaud to Ryan Gosling in "Drive."

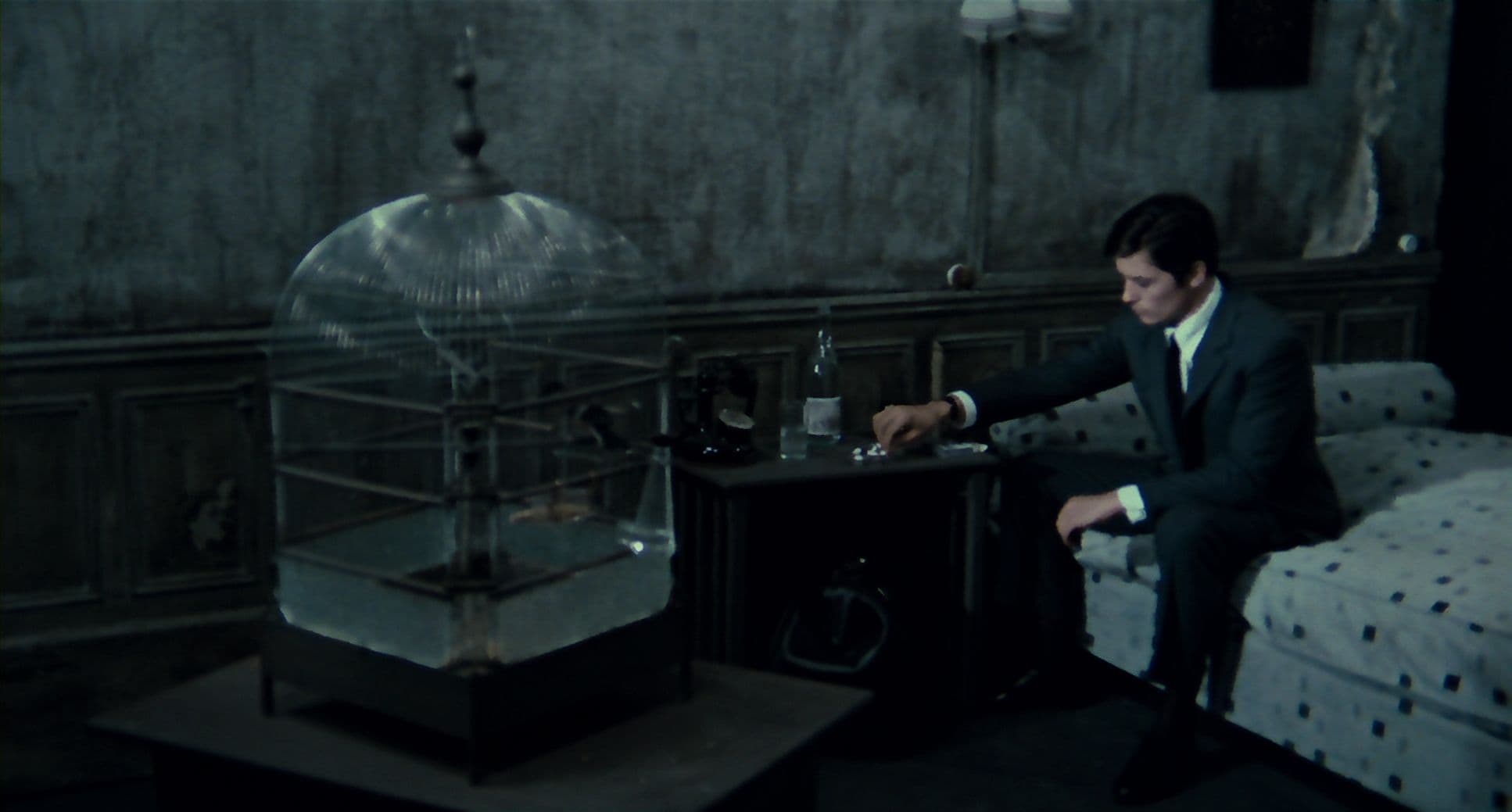

Frank Costello is a solitary hitman who finds himself pitted against law enforcement and his own associates. His existence is marked by almost monastic rituals: the hat, the white gloves, the caged bird that serves as a barometer of his inner calm. This obsessive methodicalness is not just a protection but an expression of his inflexible ethics, his personal "bushido" in a jungle of betrayals. He will begin a silent battle against his 'other self,' a conflict where the external world subtly gleams like a hostile, vengeful, looming stage. But it is also an inner conflict, a man's struggle against his own nature and his ineluctable destiny. Melville's fatalism permeates every sequence, almost as if Costello were a character from a Greek tragedy, condemned to a preordained epilogue that he accepts with resigned dignity. His quest for an impossible purity in a corrupted universe is the film's beating heart.

And where the hero stands alone, with his rituals of life and death, with values immensely superior to all else. He is not a hero in the conventional sense, but an embodiment of principles that society has long abandoned: loyalty, discipline, a perverse yet undeniable form of integrity. This purity of intent makes him an alien in a world where law is arbitrary and morality an option. The film is a meditation on the nature of professionalism and honor in a dishonorable profession, a paradox that simultaneously fascinates and repels. His figure stands out, hieratic and almost spectral, against the backdrop of a nocturnal and rarefied Paris, stripped of all superfluity, reduced to its essence: rain-soaked streets, smoky jazz clubs, bare apartments that reflect his naked soul.

A film that tastes bitter, exuding cynicism and raw romanticism. The cynicism is that of a world that exploits and then discards, that of disillusionment with any form of justice. The romanticism is that, almost from another era, of a man who still believes in a code, who is willing to pay the ultimate price to maintain his consistency. It is the melancholy of one who knows he is destined to succumb, but does so with his head held high, like the last samurai in an age of rifles and petty calculations. Melville constructs an ode to dignity in defeat, a work that, despite its apparent coldness, resonates with a rare emotional depth. His influence is evident in directors like John Woo, with his "bloodshed heroes" who share the same aesthetic of sacrifice and desperate loyalty, or in Jim Jarmusch, who has explored the figure of the melancholic "loner" in different contexts. "Le Samouraï" remains a beacon of style and content, a cinematic experience that transcends the detective genre to become pure art. A work of rare beauty and a masterful lesson in cinema as a universal language.

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...