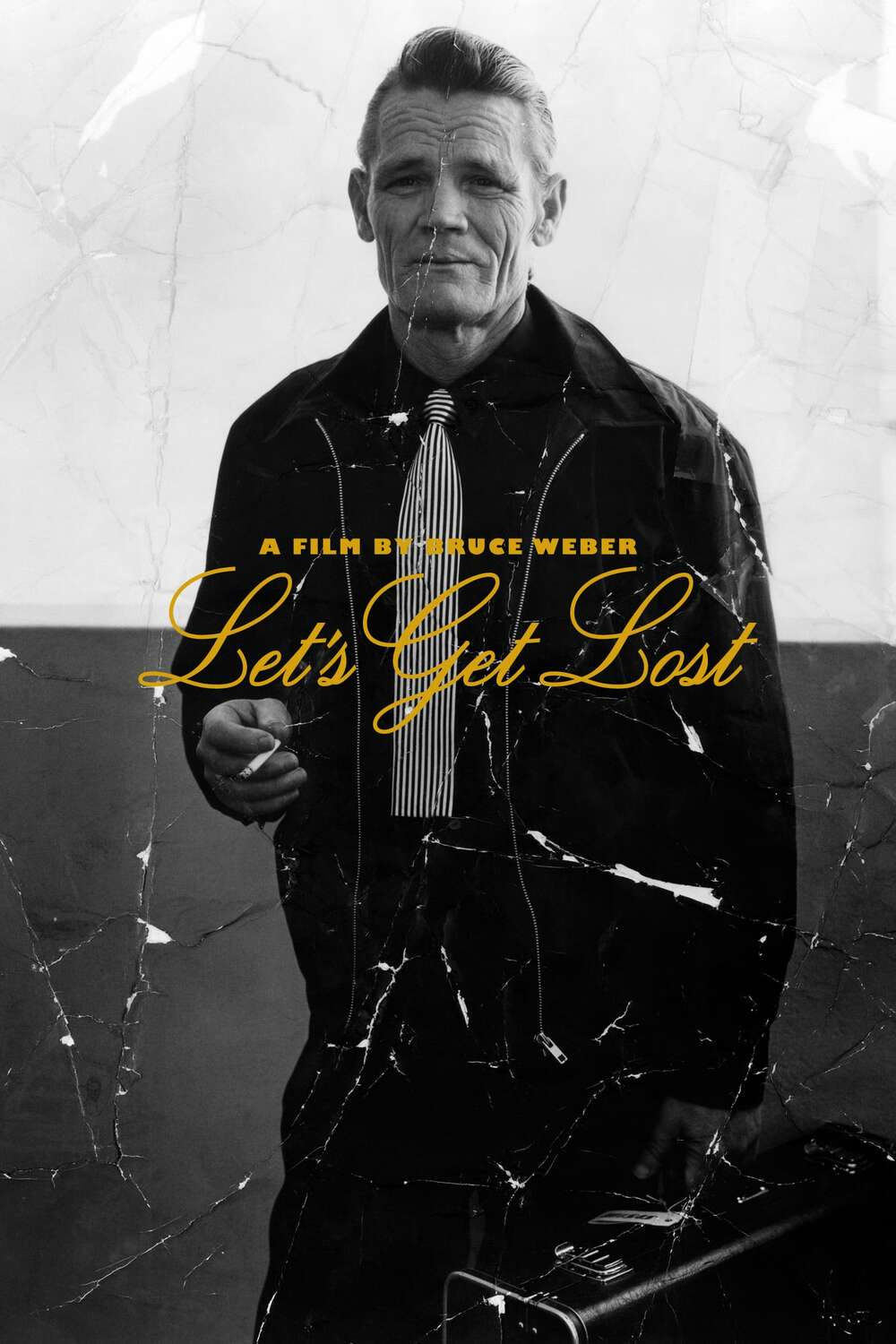

Let's get lost

1988

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

A black-and-white ballad, a visual poem, a séance in which the ghost summoned is that of the magnificent and damned Chet Baker: all this is Bruce Weber's Let's Get Lost. Released in 1988, shortly after the mysterious death of its protagonist, the film transcends the boundaries of musical biography to become an almost mythological investigation into beauty, decadence, and the inextricable link between artistic genius and self-destructive impulses. It is a work of poignant and almost cruel beauty, which has earned itself an eternal place in the Movie Canon not only for its subject matter, but for the radically new and unforgettable way in which it chose to tell its story.

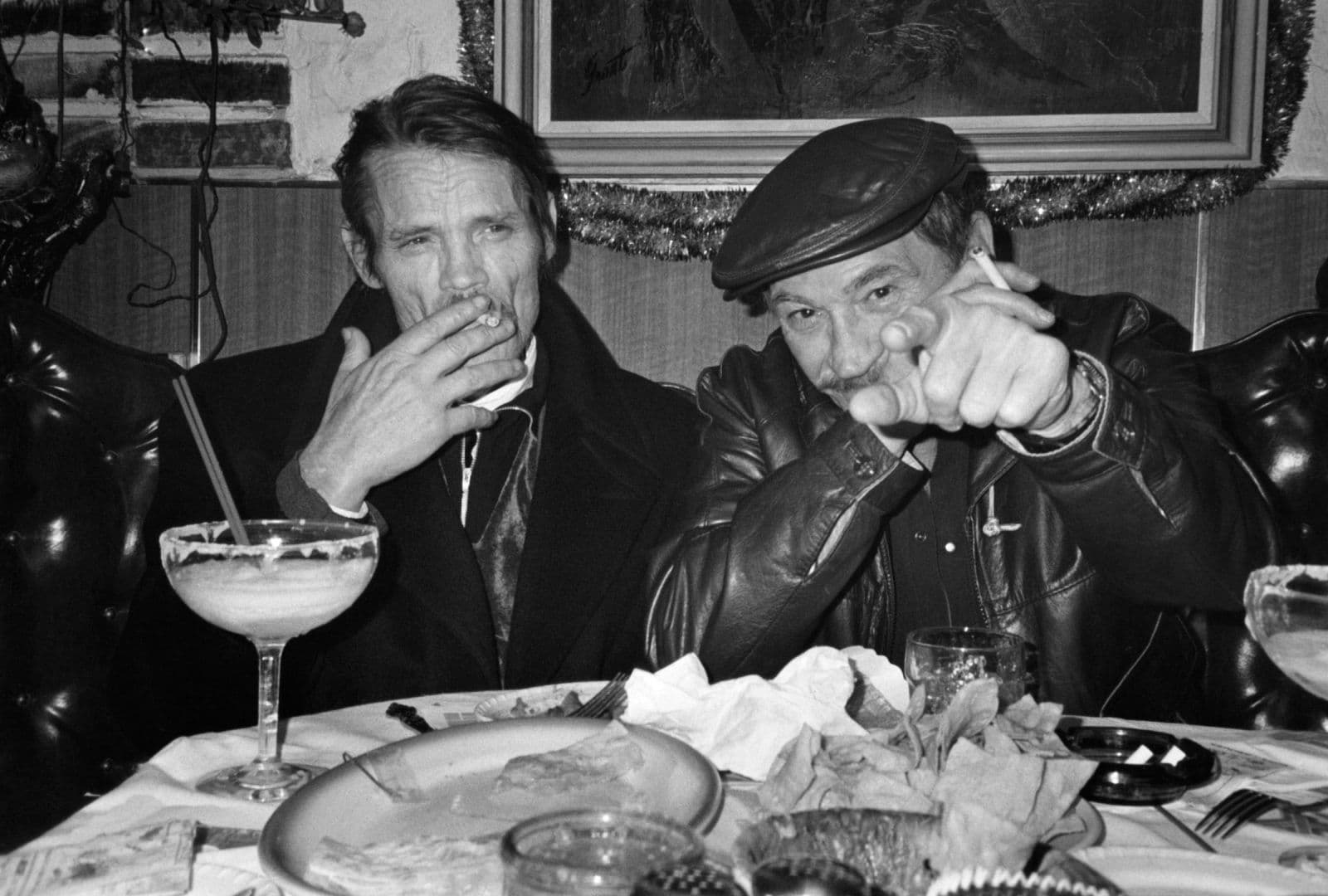

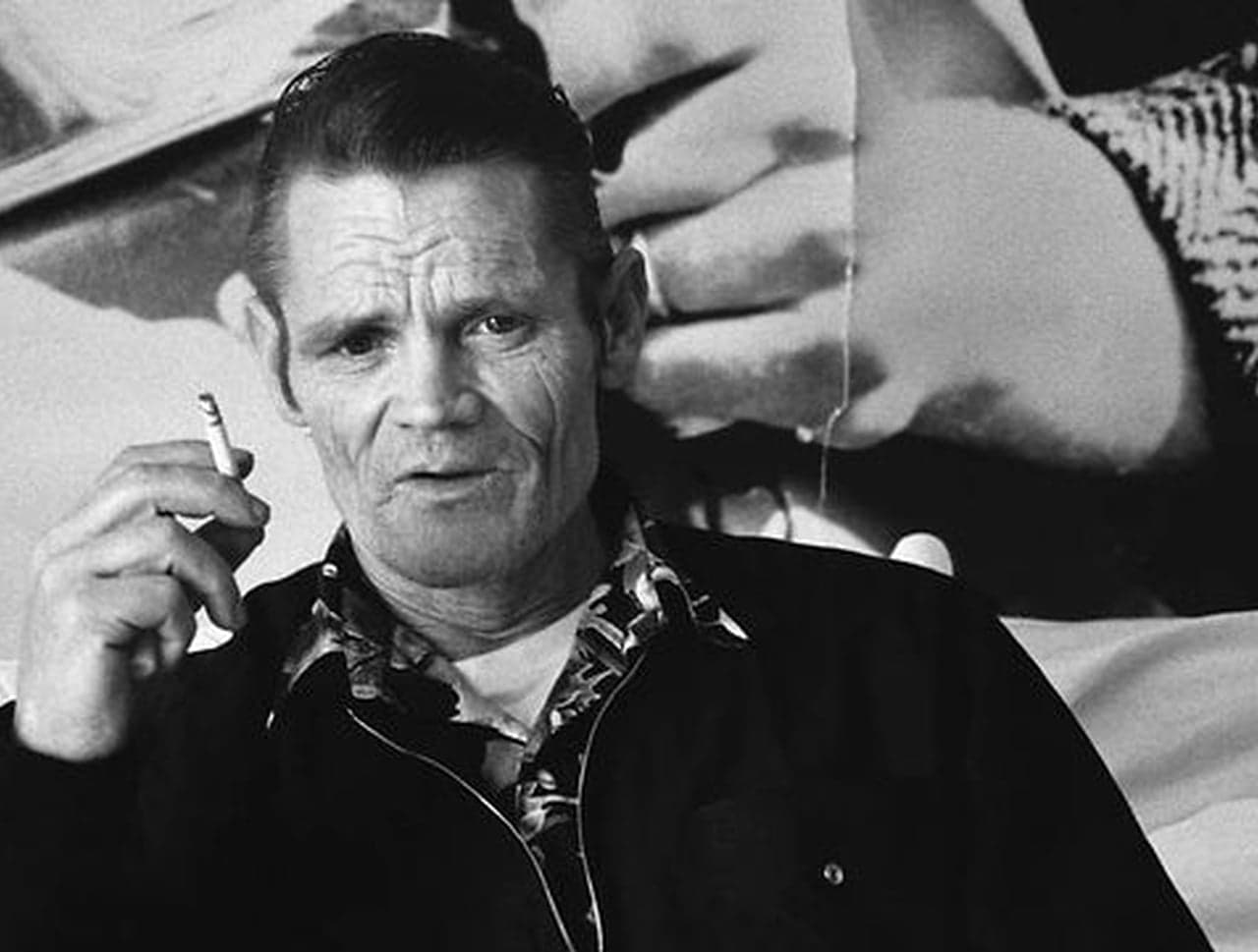

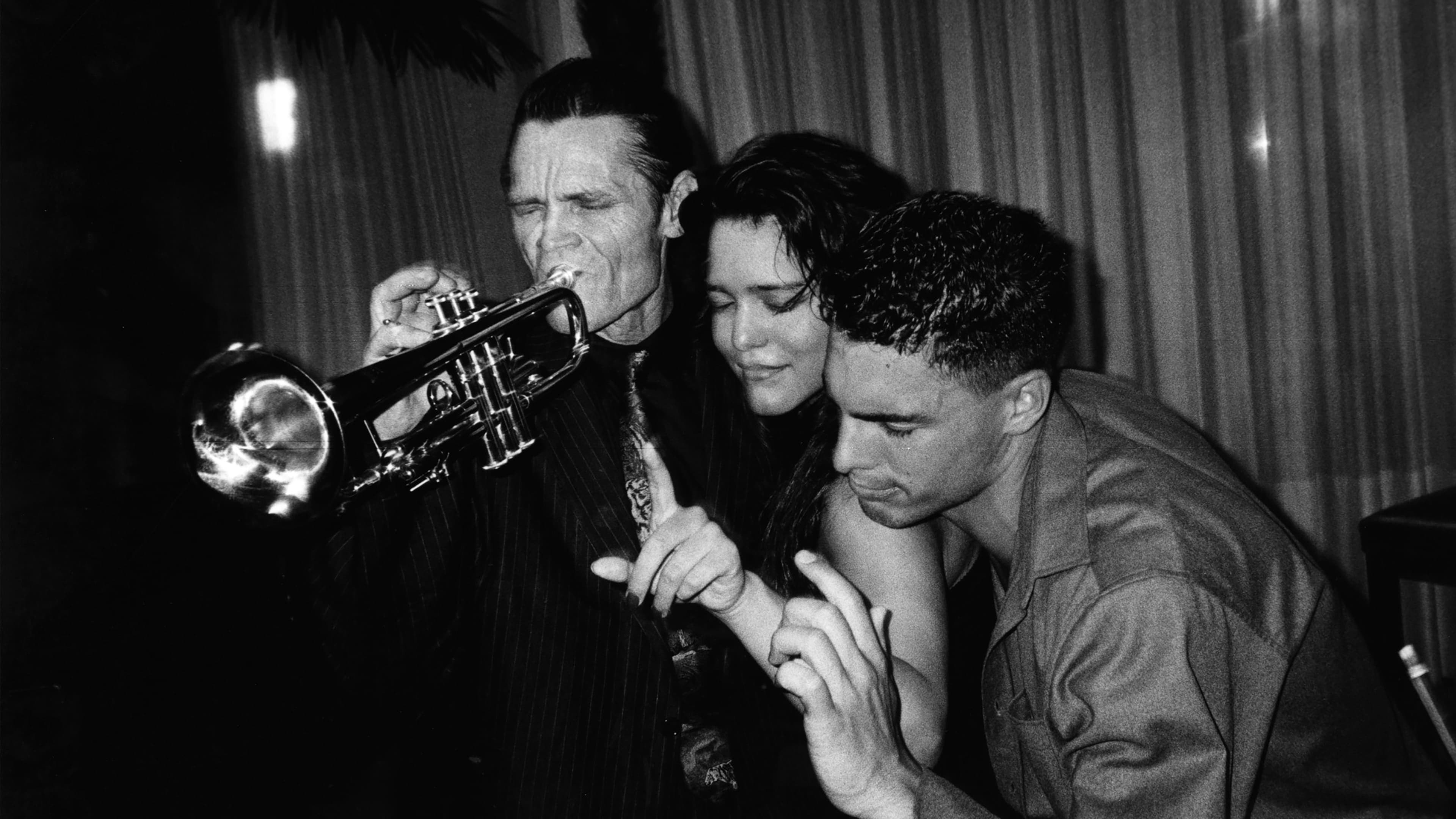

The greatness of jazz, with its improvisation, melancholy, and intrinsic fragility, is infused here into a life lived perpetually on the edge. Chet Baker is an icon, but a broken icon, a two-faced Janus of 20th-century culture. Weber shows us this in his irresolvable duality. On the one hand, there is the Chet of the past, evoked through archive photographs and film clips: an Adonis of almost unreal beauty, the James Dean of jazz, the embodiment of West Coast cool, with a trumpet that whispered lyrical ballads and a voice that seemed to break with every note. On the other hand, there is the Chet of the present, filmed by Weber: a man with a gaunt face, a map of wrinkles and pain on which life and heroin have carved deep furrows, with no front teeth, a wreck who speaks in a whisper. Yet, from this broken shell, the same pure music still emerges, miraculously. Indeed, perhaps even deeper, stripped of all youthful boldness and reduced to its most naked and painful essence.

This documentary is essential to the history of cinema because it redefined the rules of the genre. Its legacy lies in its bold and unprecedented aesthetic. Bruce Weber is not a documentary filmmaker, he is a renowned fashion photographer, and his gaze is that of someone accustomed to creating myths, to sculpting icons in light. He applies this “touch” to a subject that is the antithesis of glossy glamour. The result is a visual and moral short circuit of extraordinary power. The two hours of the film, shot in raw, dark black and white by cinematographer Jeff Preiss, do not have the style of a reportage, but of a photo shoot for a luxury magazine. Weber finds beauty in ruin, elegance in decadence. This choice is his genius and his most controversial aspect. By aestheticizing Baker's addiction and suffering, is he exploiting him? Or is he simply doing the most honest thing possible, showing how, even in total degradation, Chet's charisma and grace remained somehow intact? The film does not provide an answer, but leaves us suspended in this fascinating ambiguity.

Chet Baker thus emerges as the archetype of the romantic antihero and the cursed musical genius. He is a jazz Icarus who flew too close to the sun of fame and heroin, and whose burnt wings we observe. But he is also a stubborn survivor, a man who, despite everything, continues to create beauty. The film, moving from the past to the present, from the performance that brought Baker to success and his controversial years of “lost youth” to the moving decline of his career and his struggle with addiction, creates a dreamlike and improvised atmosphere. Its structure is not chronological but associative, much like a jazz solo. It is a collage of interviews with ex-wives, lovers, children, and musicians, alternating with dreamlike sequences of Baker driving a convertible or singing in a recording studio. It offers a rare behind-the-scenes look at the decadent life of jazz's first “bad boy.”

Jazz and cinema, after all, have almost always been a winning combination. Initially, jazz was mainly used as a soundtrack, the diegetic sound that filled the smoky rooms of film noir. But it was with the French Nouvelle Vague that jazz became the heartbeat of a new cinematic sensibility. Miles Davis' totally improvised soundtrack for Louis Malle's Elevator to the Gallows is the perfect example: jazz, with its freedom and breaking of conventions, was the sound mirror of a cinema that was tearing up the rules. Other films, such as Clint Eastwood's Bird, have attempted to tell the biographies of jazz geniuses. But Let's Get Lost does something different and, perhaps, more profound. It is not a film about jazz; it is a film that is jazz itself. Its fragmented, non-linear structure, its rhythm alternating between moments of lyricism and silent pauses, its improvised nature, all reflect the music at its heart.

It is one of the few works that manages to capture not only the history but the very soul of a musical genre. Weber's work is a work that refuses to judge. It is both an autopsy and a love letter. Weber does not present us with a saint to worship or a monster to condemn. He shows us a man, with all his dazzling talent and all his devastating flaws.

For its radical honesty, its breathtaking visual beauty, and its ability to redefine the possibilities of documentary filmmaking, this film has carved a deep groove in the cinematic iconography. It is an unforgettable elegy, the perfect epitaph for an angel with a dented trumpet who stands above everything and, with his instrument, gives us moments of pure ecstasy.

Main Actors

Genres

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...