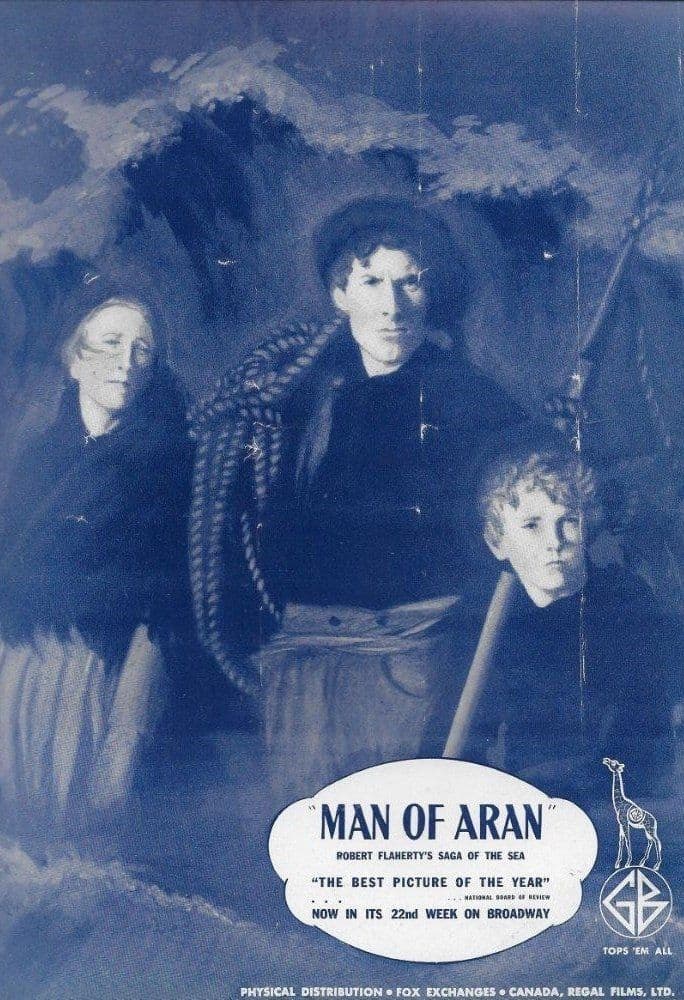

Man of Aran

1934

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

After the cold lands of Alaska, where he had unveiled the titanic clash between the Inuit man and the relentless Arctic ice, here is another ingenious exploration by Robert Flaherty into wild nature to document the arduous relationship between man and the elements. L'Uomo di Aran (Man of Aran, 1934) is a work that transcends the boundaries of documentary in the strict sense, becoming an epic poem on the struggle for survival, a hymn to the strength and resilience of man in the face of nature's cyclopean power. Flaherty, a true pioneer of documentary cinema – or perhaps, more accurately, of poetic observational cinema – transports us this time to the Aran Islands, off the west coast of Ireland, where an atavistic and fiercely independent community of fishermen daily faces the challenges of a hostile and wild environment. With a style that is at once immersive and lyrical, almost a visual ode, Flaherty shows us the lives of these men and women, their indissoluble and profound bond with the sea and the land, their incessant struggle against the elements, not infrequently bending narrative reality to enhance the drama and archetypal nature of their existence. L'Uomo di Aran is a work that indelibly marked the history of cinema, a masterpiece of visceral realism and tragic poetry that delves into reality with his tireless eye – and sometimes with intuitive staging – to convey its true essence to the audience with a distinctly scientific intent, yes, but also a deeply artistic and romantic one.

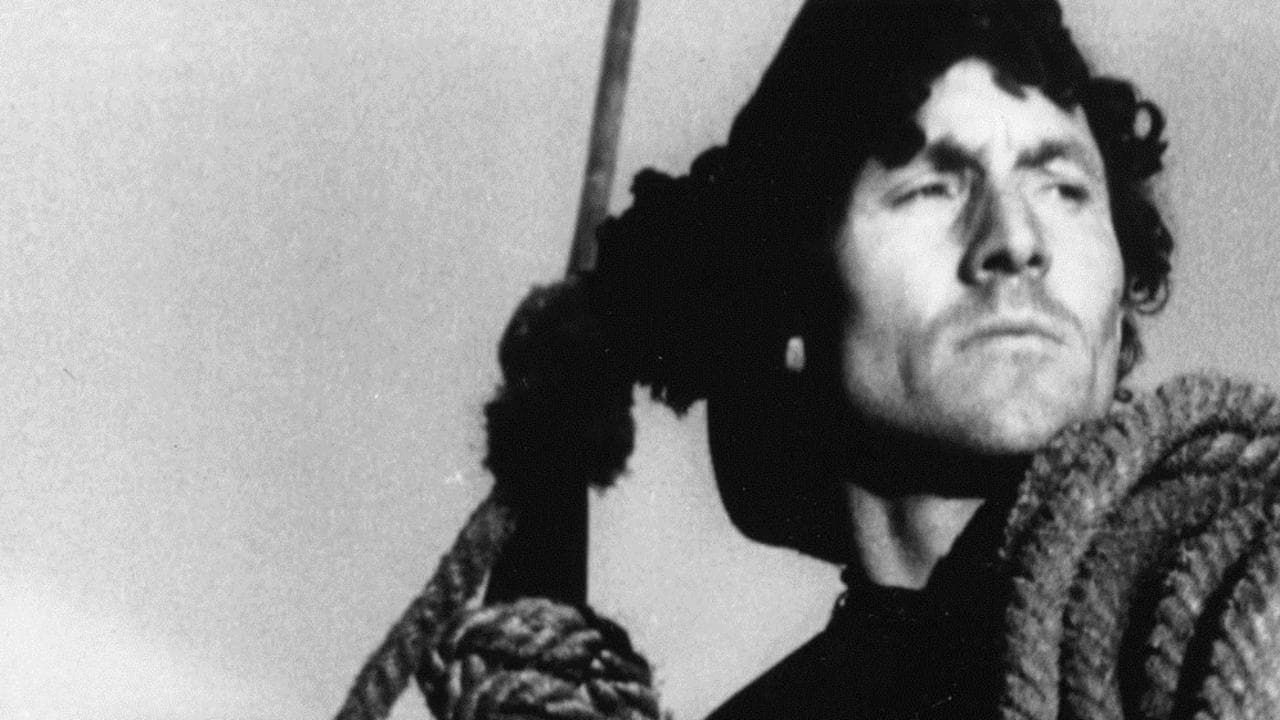

The film focuses on the daily lives of the inhabitants of the Aran Islands, a palimpsest of survival traditions and rituals passed down from generation to generation. Following a family composed of a man, a woman, and a boy, Flaherty shows us their fishing activities, the cultivation of potatoes on rocky soils fertilized with seaweed – an ingenious and exceedingly arduous stratagem to wrest nourishment from the hostile land – the construction of a robust flat-bottomed boat (the "curragh"), and the mythical, dramatic shark hunt. Flaherty's camera, with near-sculptural mastery, captures the wild and untamed beauty of the landscape, the primordial force of waves crashing with titanic violence against the formidable cliffs, the uninterrupted toil and unshakeable determination of the men confronting the stormy sea, like modern Ulysseses dedicated to an eternal challenge. The shark hunt sequence, in particular, despite having been, as in Nanook of the North, largely staged or recreated for the film's dramatic requirements – a detail that sparked debates but which Flaherty considered functional in conveying the essence of an almost mythological experience – remains one of the most memorable and viscerally powerful, a culmination of tension and pure adrenaline that highlights the courageous daring of the fishermen. Another scene that imprints itself on the viewer's memory, for its vertiginous intensity, is that in which the boy fishes standing on a dizzying cliff, a scene of precarious balance that symbolizes, with an almost pictorial power, the atavistic courage and at the same time the poignant fragility of man in the face of nature's immense and indifferent power. This image, in fact, rises to a universal metaphor, in an almost Leopardian perspective, of humanity condemned to a perpetual struggle, aware of its ephemeral existence in a cosmos dominated by blind and gigantic forces. We are introduced to a microcosm where a law divorced from all social compromise prevails, a rule that Darwinistically tends to favor the strongest, the most adaptable, the most tenacious, but which, at the same time, forges characters of extraordinary moral fortitude.

Darwin's influence on Flaherty is evident not only in his attention to human adaptation to the environment and the struggle for survival, but also in the meticulousness with which he observes the life strategies of these populations, almost as if they were biological species in an extreme habitat. Flaherty immerses himself in reality with an analytical eye in which scientific observation and anthropological synthesis find a fertile and rarely equaled meeting point. In him, the anthropological intent to approach a new culture, a world almost untouched by modernity, is especially clear, and he does so with all the respect that this endeavor entails, avoiding judgments and letting the action and environment speak for themselves. From his directorial style, which prefers long gazes and faces sculpted by time and toil, the immense love he harbors for these populations, for their extraordinary responses to a hostile environment that would seek to devour them, is equally clear. The black and white photography, raw yet sublime, enhances the contrasts and textures, transforming storms into visual symphonies and faces into maps of ancestral experiences. L'Uomo di Aran, awarded at the Venice Film Festival in 1934, is not just a chronicle of island life; it is a philosophical exploration of the human condition, an epic of resistance that resonates with the power of Greek myths and the determination of pioneer settlers. With L'Uomo di Aran, we are once again faced with a milestone in naturalistic cinema, a film that influenced generations of filmmakers, from the French Nouvelle Vague to the Italian Neorealists who admired its ability to portray the common man in his daily struggle, and certainly the Seventh Art in its noblest and most universal sense. Its emotional resonance and aesthetic power persist, making it not just a historical or anthropological document, but a timeless work of art.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...