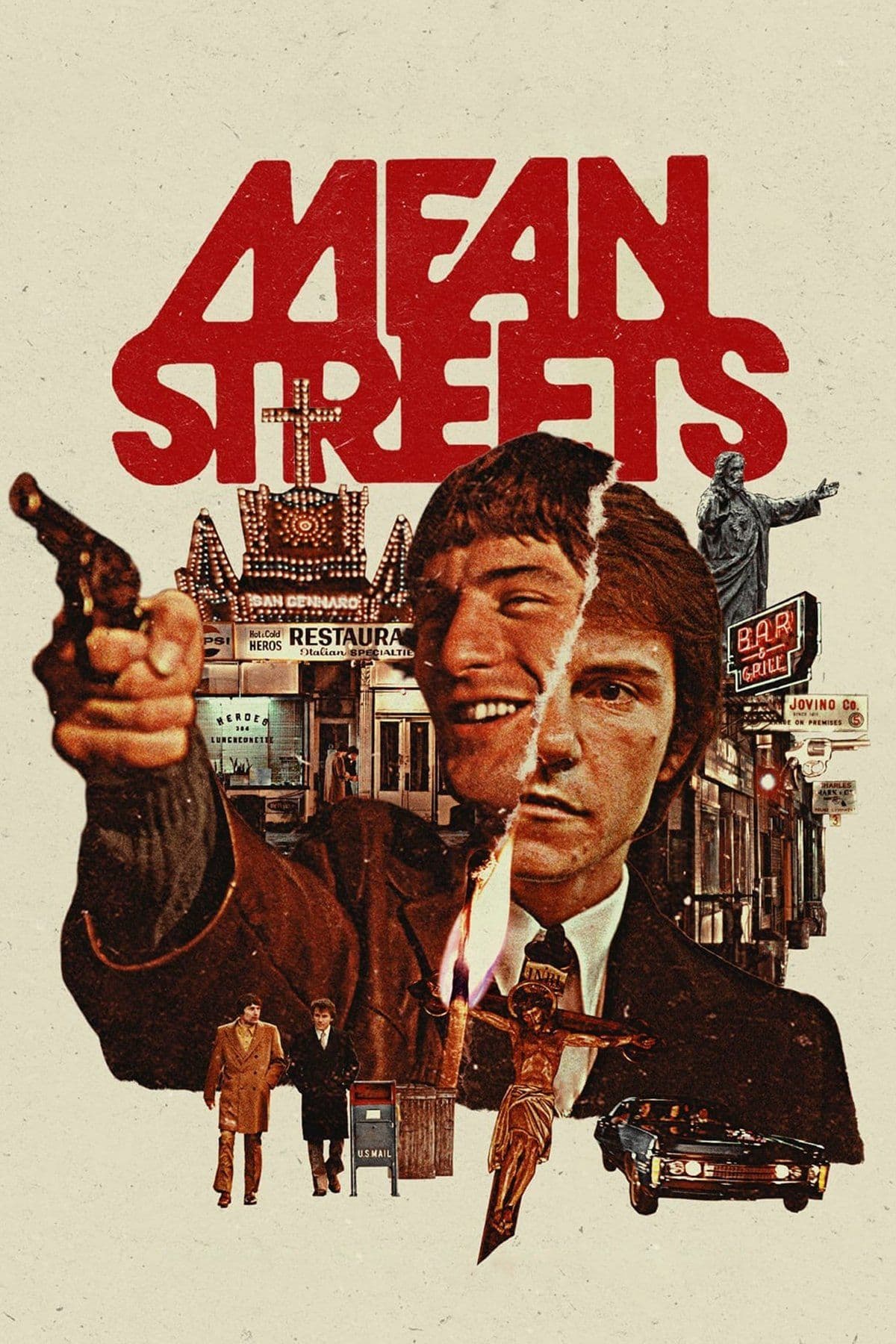

Mean Streets

1973

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

An immense homage by Martin Scorsese to the place where he grew up and which nurtured his artistic flair: New York’s Little Italy. It is not merely a backdrop, but a living, pulsating entity, almost a silent character shaping the destinies of its inhabitants. This microcosm is a crucible of faith and sin, of tribal loyalty and insidious betrayal, a territory where the ancestral traditions of immigrant parents clash with modernist anarchy and the latent violence of the new generation. Here, Scorsese not only pays homage to his personal and cinematic genesis but also dissects with a sharp scalpel the dynamics of an Italian-American community perpetually oscillating between the desire for assimilation and the stubborn adherence to often degenerate roots, foreshadowing the socio-cultural explorations that would animate later works such as Goodfellas or even the more epic The Irishman.

The story is that of a ramshackle gang of miscreants who roam the streets of the Italian quarter in search of petty illicit deals. But beyond the surface of petty crime, Scorsese delves into the psychological depths of these men, questioning the mechanisms that govern their tormented souls. They are led by Johnny Boy (Robert De Niro), torn between his love for his cousin Teresa and the mafia ambitions encouraged by an uncle, a neighborhood boss. Johnny Boy is a tightrope walker on the edge of the abyss, a reckless Icarus unafraid of burning himself in the sun, embodying nihilistic irresponsibility and an almost fatal fascination with self-destruction. And then there’s Charlie (Harvey Keitel), his tormented guardian, a modern Sisyphus desperately striving to redeem the unredeemable, whose soul is torn between Catholic devotion – a sincere and tormented faith, imbued with guilt and a search for penance – and the inescapable brutality of the streets. Theirs is a macabre dance of fraternal love and suffocating dependence, an indissoluble bond that transcends simple friendship, tinged with the nuances of a religious obsession, almost a failed Christological mission. It is the theme of redemption through the other, a leitmotif that Scorsese would later revisit, sometimes in a more sublimated, sometimes in a more explicit way, throughout his filmography, from Taxi Driver to The Last Temptation of Christ.

The streets of Little Italy are populated by grotesque characters, by gargantuan brawls, by rustic confrontations, all captured by a camera that is never a passive observer. Scorsese’s eye is feverish, tireless, pulsating to the rhythm of his characters and the city. With frenetic, almost jazzy editing, and a soundtrack that is itself a character – a kaleidoscope of era-appropriate rock 'n' roll, Italian opera, and blues – the director captures the neurosis, the urgency, the raw and at times desperate vitality of Little Italy. This viscerally immersive approach, which departs from the more linear narrative conventions of the time, owes much to the French Nouvelle Vague for its energy and street realism, but Scorsese translates it into a quintessentially American language, imbued with pulp and the sacred. His ability to blend the gritty realism of the street with almost operatic and spiritual impulses makes Mean Streets a totalizing sensory experience, a true stylistic manifesto. And behind all this, one can indeed glimpse Scorsese’s eternal love for his people, for his streets, for his birthplace, but a love that does not spare criticism nor show reluctance in revealing the dark and often brutal side of that microcosm.

There are many memorable scenes: the pool hall brawl, for instance, is not just gratuitous violence; it is a cathartic explosion of frustration and machismo, shot with an almost documentary energy, with the camera plunging into the chaos, projecting the viewer directly into the heart of the conflict, making them both accomplice and victim simultaneously. And then there’s Charlie’s monologue in church, in front of a statue of the deposition of Christ that is slowly revealed, with a delicate camera roll. This is a pinnacle of internal cinema: the statue of Christ, bathed in an almost mystical light, becomes the mirror of Charlie’s troubled soul, his personal icon of suffering and redemption. That delicate roll is not a mere camera movement, but an intimate journey into the character’s psyche, a silent interrogation of the divine that directly confronts the inexorable call of sin and the street. It is here that Charlie’s faith is measured not by abstract devotion or outward practices, but by the harsh and often merciless reality of an unforgiving environment that constantly pushes him to the limits of his morality.

But perhaps the scene that remains most vivid in memory, encapsulating the very essence of this indissoluble and damned bond, is the encounter between Johnny Boy (De Niro) and Charlie (Harvey Keitel). The venue is completely enveloped in a vermillion light that lends the action a suffocating, almost infernal atmosphere. That chromatic tone is by no means accidental: it is the color of passion and danger, of temptation and damnation that pervades their lives and the entire diegetic universe, a chromatic omen. Charlie sees Johnny Boy enter the venue, adjusting his trousers with a gesture of vulgar ostentation, accompanied by two girls he holds embraced like trophies, symbols of superficial success and an exhibited masculinity that conceals deep insecurity. Charlie remains thunderstruck by the vision – perhaps more by the aura of self-destruction and unsettling charisma than by mere astonishment – and does not approach him, watching from afar, almost troubled. This distant gaze is not indifference, but an abyss of understanding and anguish. It is the awareness of a condemnation implicit in their bond, a premonition of inevitable tragedy that hangs like a Sword of Damocles over their heads.

A scene that denotes Scorsese’s early mastery in portraying the importance of bonds of friendship in his stories, a fraternal love that creates indissoluble ties and profound human constraints upon which to hinge the narrative, but which here manifests as a true toxic symbiosis. The relationship between these two characters is not just friendship, but a reciprocal dependency that feeds on the need to complete each other and simultaneously to self-destruct. Scorsese makes it the pulsating heart of the film, elevating petty street crime to universal moral drama, anticipating the complex dynamics of emotional and criminal dependence that he would masterfully explore in Casino or The Departed.

A work that is indispensable for fully grasping Scorsese’s poetic vision in his subsequent works. Mean Streets is not just a film; it is a crossroads. It is the point where 1970s Hollywood – the so-called New Hollywood, with its quest for authenticity, its break with conventions, and its darker, more introspective gaze on American society – found one of its most original and powerful voices. This film redefined the gangster genre, stripping it of its romantic aura to reveal the sordid reality of street life, petty crime steeped in fears, neuroses, and an often warped and misunderstood religiosity. It paved the way for a more psychological, grittier type of cinema, and cemented the creative partnership between Scorsese and De Niro, one of the most iconic in cinema history, which would mark an era with its intensity and realism. Its themes – Catholic guilt, the obsession with (often failed) redemption, fatalism, a distorted code of honor, toxic masculinity – have become the hallmarks of a director who has never ceased to question the American soul, and particularly its complex Italian-American incarnation, with brutal honesty and unparalleled psychological depth. It is a masterpiece of energy and truth, a punch to the gut and a bare soul.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...