Memento

2000

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

A work that plays on the theme of memory and the implications our memories have in the cognitive processing of reality. Since the time of ancient philosophy, the concept of personal identity has been inextricably linked to the ability to remember: who one is, to a large extent, is a result of what one has experienced and preserved in their consciousness. Memento not only explores this connection but shatters it, forcing the viewer to confront the unsettling hypothesis of an existence devoid of personal narrative continuity.

The mind is the element of interconnection between the heuristic process of reality and experience. Jonathan Nolan (director Christopher's brother) builds a story around this broken link, starting with a simple question: what would happen if a man could no longer access his short-term memory and his memory reset every fifteen minutes? Christopher Nolan shapes his answer into cinematic form by adapting narration and editing in a bold, almost provocative way, elevating the so-called narrative "gimmick" to a philosophical device. Far from being a mere stylistic virtuosity, the film's fragmented temporal structure is the vehicle through which the director projects us into Leonard Shelby's tormented inner world, making us experience the same sense of agonizing disorientation and incessant search for an anchor to reality. It is an experiment in forced empathy, where the protagonist's vulnerability becomes our own.

The story, like Leonard's memory, unfolds in a non-linear fashion with alternating fifteen-minute segments lacking chronological sequence, a stylistic choice that would become Nolan's distinctive hallmark. But Memento's non-linearity is not merely the reorganization of events we admired in masterpieces like Pulp Fiction or Rashomon. Here, the narrative proceeds backward, an inverted take-off that disorients but, at the same time, makes the viewer an active investigator, forced to reconstruct the truth in the same way Leonard attempts to do. The film is ingeniously divided into two intersecting timelines: the color sequences advance backward in time, showing us the final events before those that precede them, while the black-and-white sequences proceed forward, recounting the distant past of Leonard and Sammy Jankis, the tragic figure who serves as a warning.

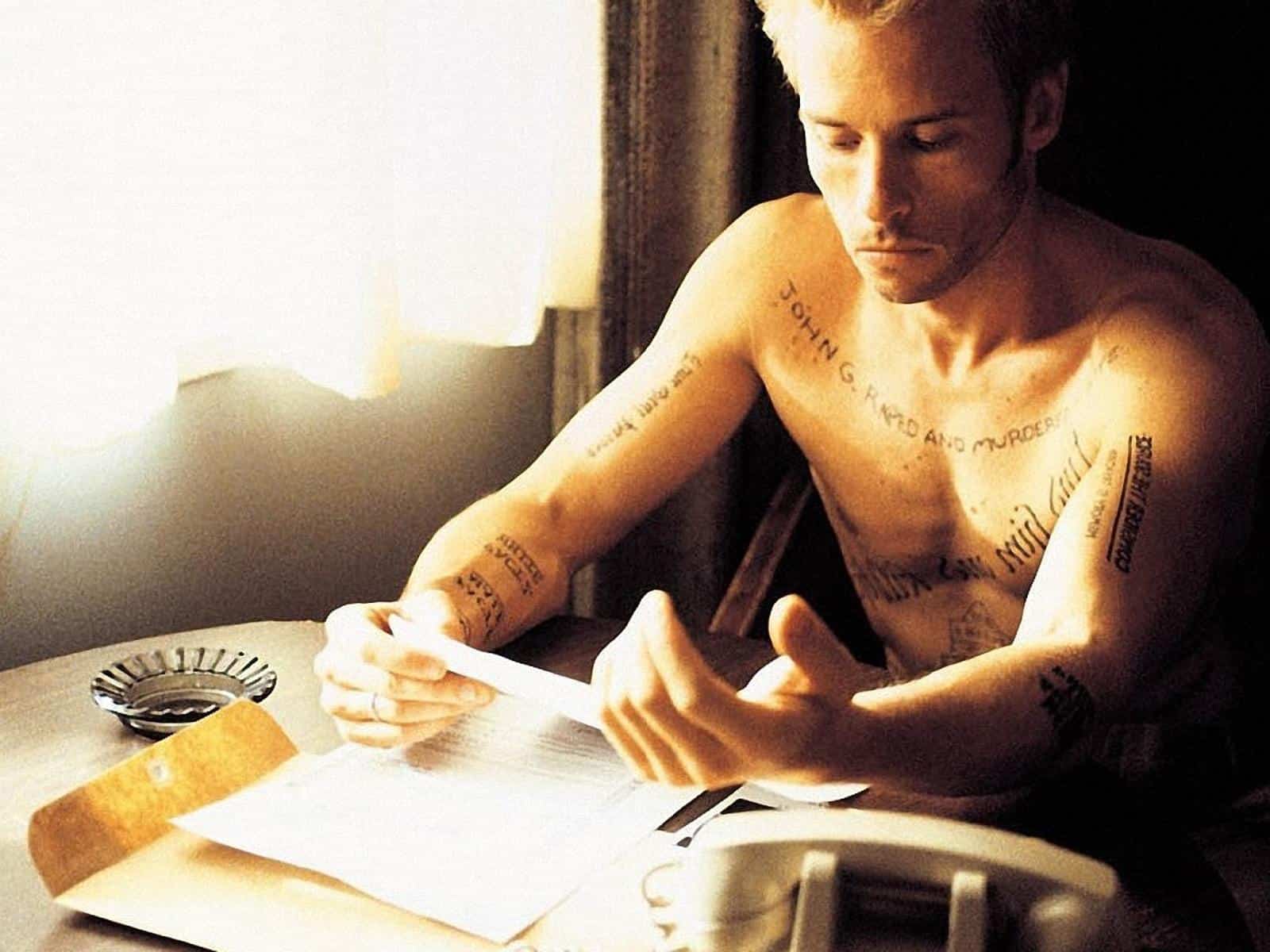

Leonard is a former insurance investigator whose wife was murdered – a narrative archetype that Nolan deconstructs with acumen. The killer is also the one who, by striking him on the head, caused the onset of anterograde amnesia, or short-term memory loss. This detail, seemingly a mere plot mechanism, transforms Leonard into a noir detective where the investigator is the most unreliable variable in the equation, a tragic hero whose investigation is a modern Sisyphus. To remember, Leonard writes everywhere: on post-it notes, on slips of paper, and more indelibly on his own body by means of tattoos, transforming his skin into a painful and paradoxically mutable map of his purpose. Every clue is a fragile foothold in the sea of oblivion, and truth itself becomes an ephemeral construct, susceptible to reinvention with each new "reset."

The story begins with Leonard's killing of Teddy, a self-proclaimed friend, and the entire work focuses on how Leonard came to the conclusion that Teddy was the killer he was searching for. This opening sequence, shown in color but with an almost monochromatic desaturation, immediately establishes the tone of moral ambiguity and cognitive uncertainty that permeates the entire film. It is a fascinating Moebius strip, a loop of flashbacks that distorts chronological progression by moving backward and giving meaning – or perhaps an illusion of meaning – to events that have already occurred. The brilliance of this structure lies in its being not just a stylistic device, but the beating heart of Leonard's drama: the impossibility of distinguishing truth from convention, justice from cyclical revenge. Nolan, in this, seems to nod to the literary tradition of authors like Jorge Luis Borges, where the labyrinth and the illusory nature of reality are central themes.

One feels a sense of anger and helplessness while watching this film, and this is precisely the kind of reaction Nolan wants us to experience so that our identification with his Leonard is complete. A psychological immersion operation that transcends simple narration, transforming the viewer into a co-conspirator and victim of amnesia. Memento was the work that revealed Christopher Nolan's crystal-clear talent to the world, marking a turning point not only for the director but for the entire independent cinema landscape. Produced with a negligible budget compared to its ambition, it demonstrated how true innovation lies in structure and conception, not just in special effects. It instantly became a cult classic, an indispensable reference for anyone wanting to understand the evolution of the modern psychological thriller. An absolutely disruptive story, with direction careful to compress inverted time and fix it into an evolving, reconfigurable fresco like a puzzle, whose pieces are revealed in a deliberately disharmonious order to maximize emotional and intellectual impact. Here one can already glimpse the seeds of that obsession with temporality and complex narrative architectures that would define Nolan's subsequent filmography, from Inception to Interstellar, up to Tenet.

Reality exists only as a mental representation within each of us, an idea that resonates with philosophical solipsism, but which in Memento is taken to the extreme: this representation resets every fifteen minutes, leaving Leonard in an existential limbo. Leonard's desperate words that close the film are not just a monologue from a man adrift, but a manifesto on the human condition and the intrinsic need for narrative and purpose. "I have to believe in a world outside my own mind. I have to convince myself that my actions still have meaning, even if I can't remember them. I have to convince myself that, even if I close my eyes, the world is still there... So, am I convinced or not that the world is still there? Is it still there? ... Yes. We all need memories to remind us who we are, I'm no different... So, where was I?" This extremely bitter epilogue offers no catharsis, but a dizzying sense of vertigo. It shows how identity is not an immutable given, but a daily construction, a continuous act of faith in the coherence of one's own story. Leonard, unable to remember, is condemned to invent meaning, to perpetuate a cycle of revenge that is perhaps the only way to give content to his fragmented existence. The film questions us about the very nature of memory as a tool not for objective truth, but for subjective construction of reality and, ultimately, of our very selves. It is a masterpiece that continues to resonate, inviting us to reflect on what it truly means to "remember" and, consequently, to "exist."

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...