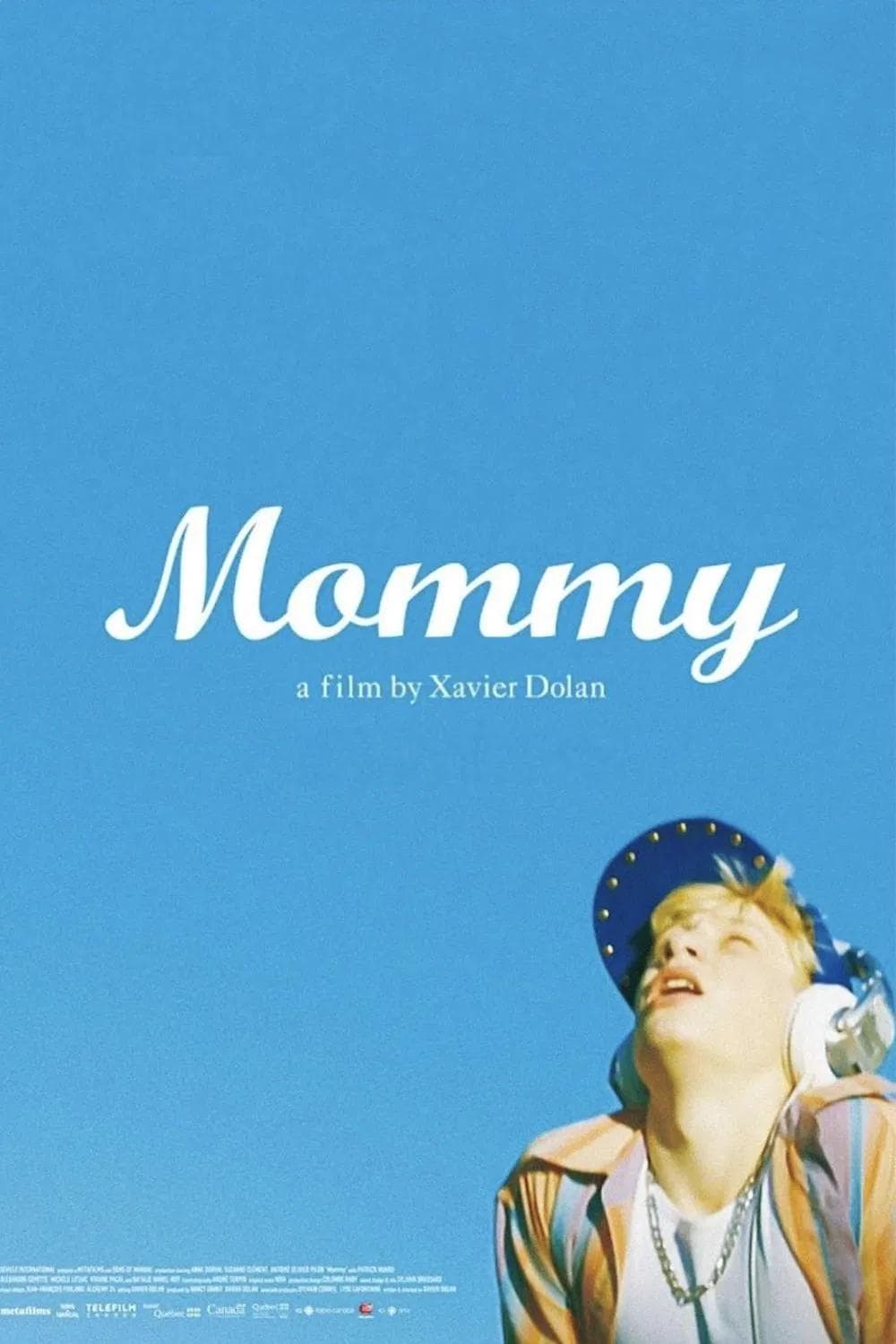

Mommy

2014

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Mommy is a film that stays with you for a long time. It's an explosion of cinema, a punk rock melodrama that grabs you by the collar and shakes you for two and a quarter hours, leaving you breathless, your ears ringing and your heart broken, but strangely, wonderfully alive. The then 25-year-old “enfant terrible” of Quebec cinema has created his masterpiece here, a work of almost brazen vitality and formal audacity that explores the most primordial and chaotic of bonds, that between a mother and her child, with an intensity that is almost unbearable. Like its protagonists, the film is imperfect, noisy, and at times irritating, but its emotional honesty is so brutal and dazzling that it is an essential contemporary cinematic experience, whose legacy will long live on in the consciousness of many filmmakers.

The story is an emotional rollercoaster ride. Diane “Die” Després, an exuberant, foul-mouthed widow, decides to take back her 15-year-old son, Steve, who suffers from severe attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Their relationship is both a battlefield and a refuge. They love each other with an almost animalistic ferocity and hurt each other with the same intensity. Their life is a constant swing between moments of disarming tenderness and sudden, terrifying outbursts of violence. This precarious balance is disrupted by the arrival of Kyla, their neighbor, a stuttering teacher on leave due to an unspecified trauma. Together, this trio of misfits forms a bizarre and touching family of choice, an island of fragile stability in an ocean of chaos.

The first thing that strikes and unsettles the viewer is Dolan's most radical formal choice: a 1:1 aspect ratio. The screen is a perfect square, a visual prison that forces us into an almost suffocating intimacy with the characters. This is not the affectation of a first-time director, but a powerful philosophical choice. The narrow frame perfectly reflects the existential condition of the protagonists: they are trapped. Die is trapped by her economic and social condition, Steve by his illness and anger, Kyla by her traumatic mutism. There is no room to breathe, no horizon, only the intensity of their faces, their screams, their embraces. But then, twice in the film, a cinematic miracle occurs. In moments of maximum euphoria and hope—particularly in the famous sequence where Steve races by on his skateboard to the notes of Oasis' Wonderwall—the character literally pushes the edges of the screen with his hands, widening the frame into a liberating widescreen format. It is a breathtakingly beautiful meta-cinematic gesture, a moment when the film itself seems to take a deep breath, when the form bends to express the explosion of joy and possibility of its characters. The performances of the central trio are nothing short of volcanic. Anne Dorval, Dolan's muse, is a magnificent Die, a concentration of maternal strength, vulgarity, and vulnerability. Antoine Olivier Pilon is an electric and unpredictable Steve, capable of switching from frightening violence to childlike sweetness with a snap of his fingers. And Suzanne Clément offers a performance of rare subtlety as Kyla, the silent catalyst whose gradual healing occurs by osmosis, absorbing the chaotic vitality of her new friends. Together, they don't act, they live on screen, creating a core of authenticity so powerful it hurts.

Dolan's aesthetic is a pop maximalism that owes much to masters such as Pedro Almodóvar, for his bold use of color and the centrality of powerful, imperfect female figures, and to Wong Kar-wai, for his ability to use pop music not as a mere soundtrack, but as a true emotional language. The songs of Céline Dion, Dido, Counting Crows, and Lana Del Rey are not nostalgic background music. They are the emotional lingua franca of characters who often cannot articulate their deepest feelings. The scene in which the three dance and sing at the top of their lungs in the kitchen to the Counting Crows' Colorblind is a moment of pure grace, a domestic epiphany in which music becomes the only form of communion and catharsis possible. In this, Dolan's approach can be compared to a form of cinematic Pop Art: he takes elements of “low” or mass culture and elevates them to a vehicle for the highest and most universal of emotions, finding the sublime in kitsch and the tragic in a chart-topping song.

But beneath the surface of family melodrama, the film hides a sharp political soul. Dolan sets the story in a near-future Canada where a fictional law, S-14, has been passed allowing parents to forcibly commit their children with behavioral problems to psychiatric institutions with a simple signature. This law hangs over the story like a sword of Damocles, transforming Die's personal drama into a political and social dilemma. Her struggle to keep Steve with her is not just a battle for love, but a battle against a system that prefers institutionalization to care, exclusion to support. It is a fierce critique of a society that, behind a facade of efficiency, abdicates its responsibility to the most vulnerable.

Mommy is a visceral experience, a punch in the stomach followed by a caress. It is a film about maternal love as a force of nature, an unconditional, imperfect, sometimes toxic love, but always, desperately, present. Its inclusion in the canon is a tribute to a daring cinema that is not afraid to be excessive, sentimental, and unashamedly emotional. The final image of Steve running, in a gesture of desperate and ambiguous liberation, is the perfect seal on a work that screams, with all the strength it has in its body, the beauty and tragedy of being alive.

Main Actors

Genres

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...