Nanook of the North

1922

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

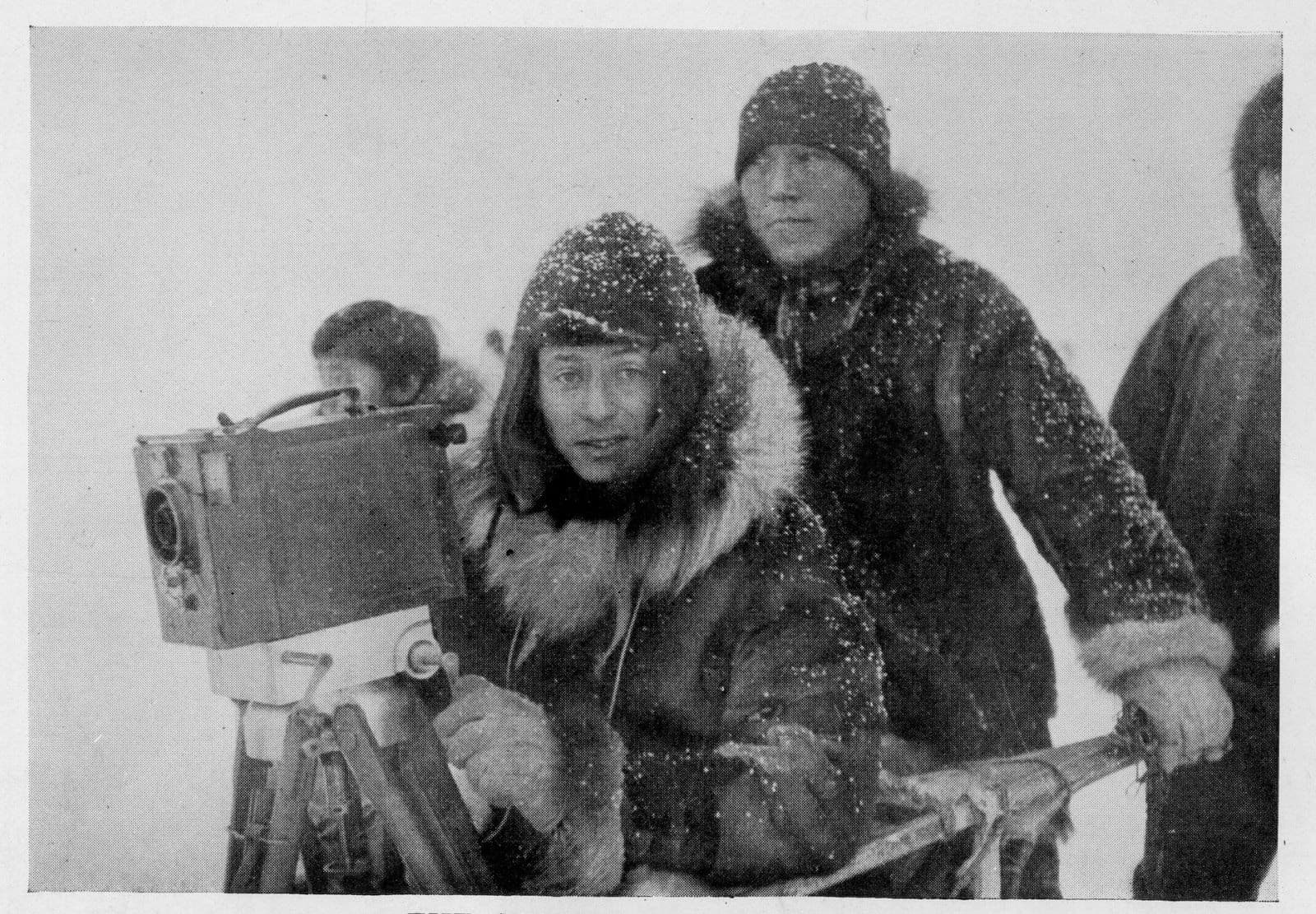

Director

Our history of cinema also includes a mining engineer, explorer, and adventurer like Robert J. Flaherty. How is that possible? you might ask. The fact is that Flaherty, during his extensive exploration of the lands in northern Canada, filmed this documentary with the ethnological intent of providing the West with an understanding of the living conditions of the peoples of the Great Ice. This peculiar genesis, far from the nascent Hollywood studios or European avant-garde movements, imbues Nanook of the North with an almost archetypal purity of intent. Flaherty was not a filmmaker trained in academies, but a man of the world, whose camera became an extension of his spirit of discovery and his deep fascination with other cultures. At the beginning of the 20th century, the Arctic was still a mysterious and fascinating territory, a final frontier of Western civilization, and the exploration of these remote regions aroused great scientific and popular interest. Cinema, at the time a relatively new and rapidly asserting medium, was defining itself as a powerful tool not only for entertainment but also for communication, dissemination, and, in still unexplored ways, for testimony. Flaherty, with surprising foresight, grasped the potential of cinema to tell intrinsically human stories and to document the reality of remote existences with an immediacy otherwise inaccessible. It was not merely a reportage, but an attempt to give cinematic form to lived experience. And naturally, a work of such vividness, of such powerful documentary force, almost revolutionary for its time in its immersiveness, emerged, one that could not go unnoticed in film clubs and film criticism fanzines, immediately establishing itself as an indispensable reference point for anyone wanting to understand the nascent forms of realist cinema.

The story is that of Nanook, of Inuit ethnicity (more precisely an Inuk, whose real name was Allakariallak), and his family, a narrative that unfolds with the gravitas of an epic tale while maintaining the intimacy of a personal portrait. Survival in unthinkable conditions – the biting frost, the scarcity of resources, the relentless white vastness – is not merely an epiphenomenon here, but the very essence of existence. Daily life becomes an act of harmony with a nature as hostile as it is, in its grandeur, profoundly fascinating and terrible. The film shows us, through the cyclical succession of Arctic seasons, the daily struggle of this community to survive in an environment that is both a matrix and a challenger. From seal hunting, a ritual of patience and cunning that reveals a deep knowledge of the ecosystem and animal behavior, to the construction of the igloo, a masterpiece of vernacular engineering erected with surprising dexterity to provide refuge from the extreme cold, Nanook and his family face the challenges of nature, from the harsh and dark winter season to the brief and intense summer of perpetual light. Flaherty, with his camera as if it were a participatory and respectful eye, captures the majestic beauty and the raw, disarming authenticity of Arctic life, showing us a people deeply connected to the land, its immemorial rhythms, and its unwritten laws. Through the powerful images and narration, at times didactic but always evocative, the director invites us to reflect not only on the resilience of the human spirit in the face of adversity, but above all on the symbiotic and, at times, brutal relationship between humankind and nature, and on the fragile yet sublime beauty of a millennia-old culture that, unfortunately, was already then on the path to an inexorable decline, making the film also a precious act of "salvage ethnography," an attempt to preserve a record of a culture before it vanished.

Nanook of the North is, rightly, considered one of the first and most influential examples of modern documentary, a true archetype that has shaped the collective imagination regarding the representation of indigenous cultures. Flaherty, with his film, not only helped to define the embryonic canons of the genre but also raised fundamental questions about the ethics and aesthetics of representing reality. He demonstrated how cinema could be used not only to observe but also to interpret and represent reality, forging a language that went beyond mere "seeing," tending rather towards "feeling." It is here that his brilliant intuition of "poetic realism" lies, an approach in which reality is not simply recorded but filtered and reassembled through an intrinsically subjective and artistic lens. The images are often suggestive and evocative, charged with a visual lyricism that elevates the everyday to the epic, and the narration is slow, meditative, almost hieratic, allowing the viewer to fully immerse themselves in an other time and space. Flaherty did not merely "create" the documentary genre in the sense of codifying its rules; rather, he opened its doors, charting a path that would influence generations of filmmakers, from John Grierson – who would coin the term "documentary" and theorize its social function – to the Italian neorealists who would seek truth in everyday life, and even to "direct cinema" directors. His greatest insight lies in the searing realism of the reportage, in the ability to present a raw succession of life scenes with such perceived authenticity that his inevitable staged elements, the small "betrayals" of reality for narrative or filming needs (such as the famous scene of the larger igloo built specifically without a roof to let in light for filming, or the use of already obsolete tools to emphasize the "purity" of a culture), become almost irrelevant in the face of the overall emotional impact. Despite modern criticisms of his "staged" methodology, the greatness of this work lies precisely in its silent act of purity, in its ability to dissolve cinematic artifice to make way for a Nature of searing beauty captured in its wild, untamed unfolding, a hymn to life apprehended in its most essential and vulnerable form. Over a century later, Nanook of the North still deeply moves us, prompts us to question our place in the world, and reminds us of cinema's timeless power as a bridge between cultures and a window into the human soul.

Main Actors

Genres

Countries

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...