Network

1976

Rate this movie

Average: 3.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

A corrosive descent into the cynical world of media and the diabolical persuasive powers these communication channels exert on public opinion. Lumet does not merely denounce; he dissects, with the lucidity of a surgeon, the ruthlessness of a pathologist, and the profundity of a philosopher, the arteries and veins of a sick system that, already in the 1970s, showed the first, devastating symptoms of what would become our present. The director delves into the power of communication and mercilessly exposes its contradictions, inhumanity, and moral baseness, revealing how the obsessive pursuit of profit can corrupt all ethics, transforming information into a commodity and truth into a spectacle.

It is a profound and intelligent work in its stinging sarcasm, amplified by an Oscar-winning screenplay by Paddy Chayefsky, a true tour de force of writing that elevates the film far beyond simple satire. Chayefsky, already a master wordsmith with a background in television, infuses every line with a contained rage and a vision that borders on prophecy, anticipating with terrifying precision the advent of infotainment, "reality TV," and the post-truth that today permeates every aspect of public discourse. His script is a masterpiece of sharp dialogues, often incandescent monologues that explode with the force of an apocalyptic sermon, a funeral hymn to reason and morality.

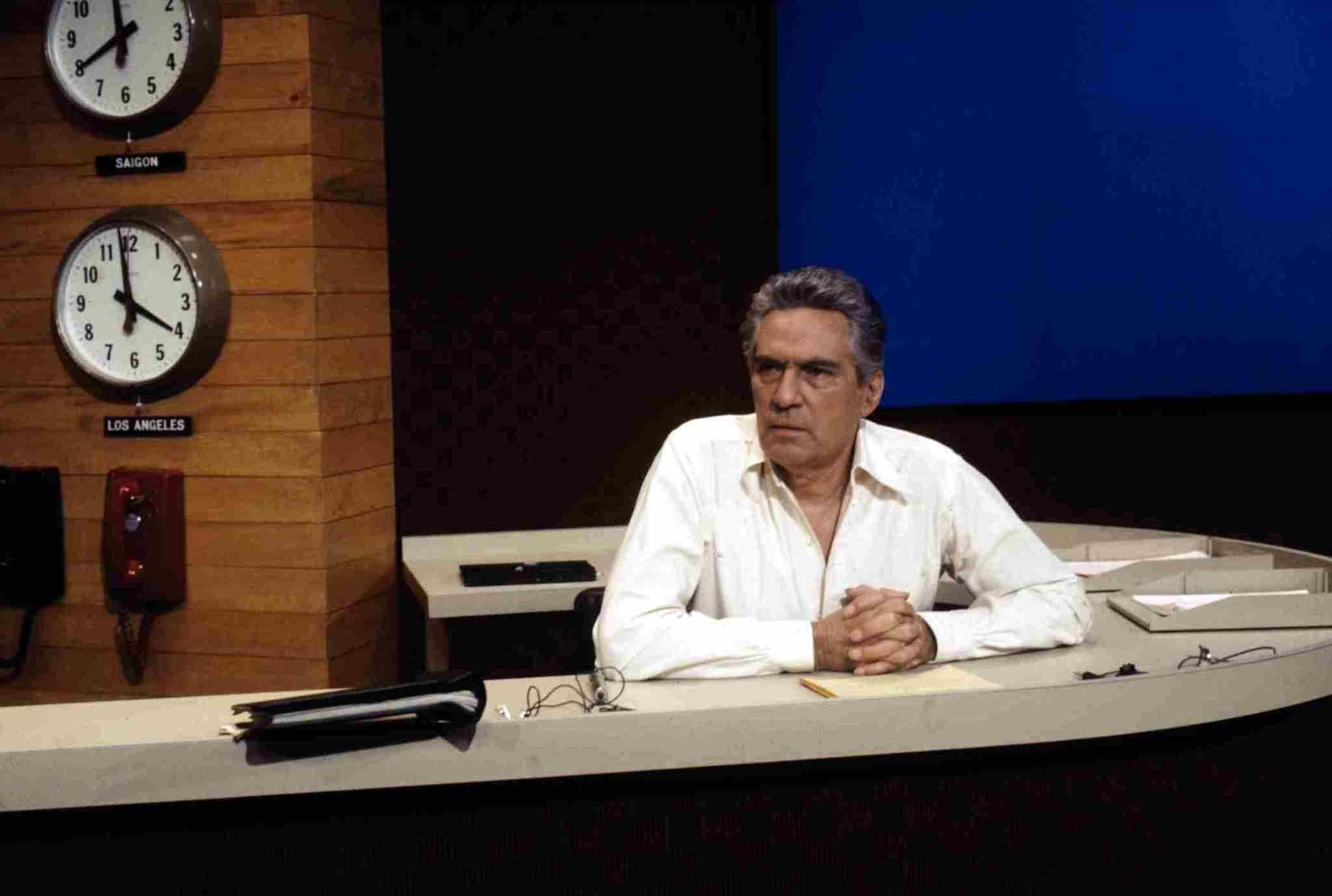

Howard Beale is a television anchorman on the verge of being fired from the UBS network. In a final desperate message before the cameras, the man, distraught and in the throes of an existential crisis, announces his suicide live on air. This is the initial paradox: a desperate act that, far from being ignored, is immediately capitalized on. Suddenly, Beale becomes a national phenomenon with millions of people becoming his disciples, transforming abnormality into an irresistible attraction for the public and, consequently, for advertisers. Beale thus becomes a kind of thundering prophet railing against the injustices of society, against all the daily wrongs that every citizen must endure. His is the voice of the "furious people," screaming from the windows of their televised isolation the mantra "I'm mad as hell, and I'm not going to take this anymore!" A kind of proto-populism that these days lends itself to many analogies with political and social movements that ride the wave of widespread resentment, transforming anger into an emotional trigger, devoid of real content, yet incredibly effective.

Naturally, behind him are the television executives – in particular the cold and calculating Diana Christensen (portrayed by a glacial Faye Dunaway, also an Oscar winner), the embodiment of a new, inhuman corporate aesthetic – who use the man to boost audience ratings. They care little about the message he broadcasts from their screens; what matters is the mere numerical data, the soaring viewership curve, the multiplying profit. In this spiral of cynicism, even live death is not a limit, but a new frontier to explore to maximize market share. The dehumanization of the medium is reflected in the dehumanization of the characters, who move like pawns on a chessboard where the only rule is the survival of the most unscrupulous.

The acting performances are supporting pillars of this cathedral of disillusionment. Peter Finch, posthumously awarded an Oscar, is electrifying and tragically authentic in the role of Howard Beale, transforming his character from a pathetic wreck to an involuntary prophet, victim, and executioner of a system that devours him. His transformation is terrifying, moving from an authentic cry of pain to the alienation of a media star, up to his tragic and inevitable end. Alongside him, William Holden delivers a performance of melancholic dignity as Max Schumacher, the old-school director who desperately tries to salvage a glimmer of journalistic ethics in a maddening world, representing the last stand of a journalism that was still based on responsibility and not on sensationalism.

Quinto Potere (Network) is not just a sharp critique of the media; it is an almost sociological analysis of television's impact on the collective psyche and democracy. The film is a "dark comedy" that goes beyond simple humor to reveal the absurdities and intrinsic atrocities of a system that devours its own children. Lumet, a master at creating claustrophobic atmospheres and dissecting institutions (as already demonstrated in 12 Angry Men or Serpico), here applies his magnifying glass to the television network, transforming it into a madhouse where fiction is the only acceptable reality. The bitter irony of an era that, in the euphoria of its technological evolution, did not yet perceive the deadly trap of the "global village" distorted by spectacularization.

Cynical, bitter, ruthless: a film that, released during a period of great disillusionment for post-Watergate and post-Vietnam America, fits perfectly into the vein of "New Hollywood" that was not afraid to delve into the wounds of society. But its importance transcends mere historical-geographical context. It is a universal warning, a lucid hallucination that has unfortunately become reality. A film that teaches us Italians, and all who inhabit this digital age, to understand how and why we have arrived here, unveiling the genesis of a world in which information is indistinguishable from propaganda and pure emotion prevails over reason, perhaps making us all disciples of some modern Howard Beale.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...